What’s it like to be in a gender or sexual minority at CERN, one of the most multicultural labs on the planet? Louise Mayor reports

As your bus pulls away from Geneva Airport, you gaze at the Jura mountains towering ahead as your thoughts turn to what lies at their feet: the CERN particle-physics laboratory. Home of the Large Hadron Collider, home of discovery, soon you will arrive at one of the hottest places for science on the planet.

You’re excited, yet slightly apprehensive about meeting your workmates. You reckon they’ll share your enthusiasm for scientific discovery, but with thousands of people at CERN from a mix of the lab’s 21 member states, and more countries besides, what will your colleagues be like? How will they react to you – your personality, your nationality, your beliefs, your gender, your ethnicity, your sexuality?

Marco Van Woerden, now a PhD physicist working on the ATLAS experiment, first arrived at the lab in 2010 as a CERN summer student. Having grown up near Amsterdam in the Netherlands – the first country in the world to introduce gay marriage – he was used to a liberal attitude towards sexual and gender minorities. “I was 22 and had already been in a long-term relationship back home. I had told all my friends and family that I was gay and they had accepted it,” he says.

For accommodation, Van Woerden was placed at the CERN hostel in a shared room with a Finnish man he’d never met. “I suddenly found myself wondering how I should behave,” he says. “After all, the ‘social rules’ could be different. How would I tell him that I was gay? Would I have to? I did not have the self-confidence nor the past experience to help me to answer these questions.”

Van Woerden explains that his concerns about societal norms at CERN were tied to a lack of visibility of other gay people. “I felt – against my better judgement – that I was the only gay guy at CERN,” he says. “It was not really discussed among the students and there was no gay club at CERN.”

Need for a network

Van Woerden was not the only newcomer to notice the lack of a visible LGBT community. (LGBT stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender, but it generally refers to all gender and sexual minorities.) Another physicist who arrived in 2010 was Aidan Randle-Conde, who was embarking on a stint as a postdoc on the CMS experiment. Randle-Conde had studied physics at the University of Oxford, UK, before completing a PhD at Brunel University London and then doing a postdoc at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory near San Francisco, US. “These are all very liberal places with strong LGBT presences,” says Randle-Conde, adding that he had found his time at SLAC especially welcoming. “When I found out that CERN had no LGBT group, I was shocked and felt quite sad.”

Randle-Conde – who is now based at the Université libre de Bruxelles and continues to work on the CMS experiment – had been an on-and-off LGBT rights campaigner in his spare time since 2001, including a sabbatical as vice-president of the student union at Oxford, when he campaigned for queer rights and other issues such as disability and racial equality. With this experience in hand, in December 2010 he founded the group LGBT CERN together with an old friend from Oxford, Ian Randall, who was then editor of the ALICE collaboration’s newsletter, ALICE Matters. (Randall has written for Physics World several times as a freelance author.)

“One of the main reasons I wanted to set up the LGBT CERN group,” says Randle-Conde, who took the reins as its leader, “was to create a safe space for LGBT people and their allies where they could meet and create a social group.” He explains that one of the main problems most people find when they move to CERN is social integration, since they come from different parts of the world, often not speaking French, and perhaps not staying for long.

For its members, LGBT CERN filled a gap in CERN’s social community. Van Woerden eventually told his summer-internship roommate that he was gay; his roommate replied that it was “not a big deal” for him; and that was that. However, when Van Woerden went on to secure a contract as a technical student on the ATLAS experiment, he didn’t tell his colleagues he was gay, fearing it might affect his future career in particle physics. “In some ways I had become ‘closeted’,” he says. Once LGBT CERN was set up, Van Woerden joined and found that meeting other gay people at his workplace gave him confidence. “The existence of the LGBT club helped a lot,” he says. “I started telling people I am gay.”

Van Woerden’s new network of friends also gave him the courage to deal with some homophobic behaviour he encountered. “I had a rather disturbing experience with a guy who came into my office from time to time to work with a colleague of mine,” he explains. “He made homophobic jokes; not necessarily directed at me, but I was in the room and it made me feel uncomfortable.” The situation was resolved when Van Woerden spoke with his colleague; he never saw the homophobic man again. But, he adds, “I would never have had the courage to take action if I hadn’t had full confidence that people would back me up.”

A member of LGBT CERN, who prefers to remain anonymous, says that at first he was reluctant to join. “I expected that I would have to be out – a loud and proud LGBT person – identifying myself as a homosexual male in public,” he says. This would have been troublesome for him, he explains, as he is not ready to be out. He also felt that his religious beliefs might cause “some level of friction” with club members, since homosexuality and religious beliefs do not always go hand in hand. However, when he joined the club he was amazed to find that “they welcomed me as an ‘in the closet’ – religious – homosexual person with open arms”. He believes that a safe and welcome platform is needed to make friends and learn the social norms of CERN–Geneva society and that, for him, LGBT CERN is this platform.

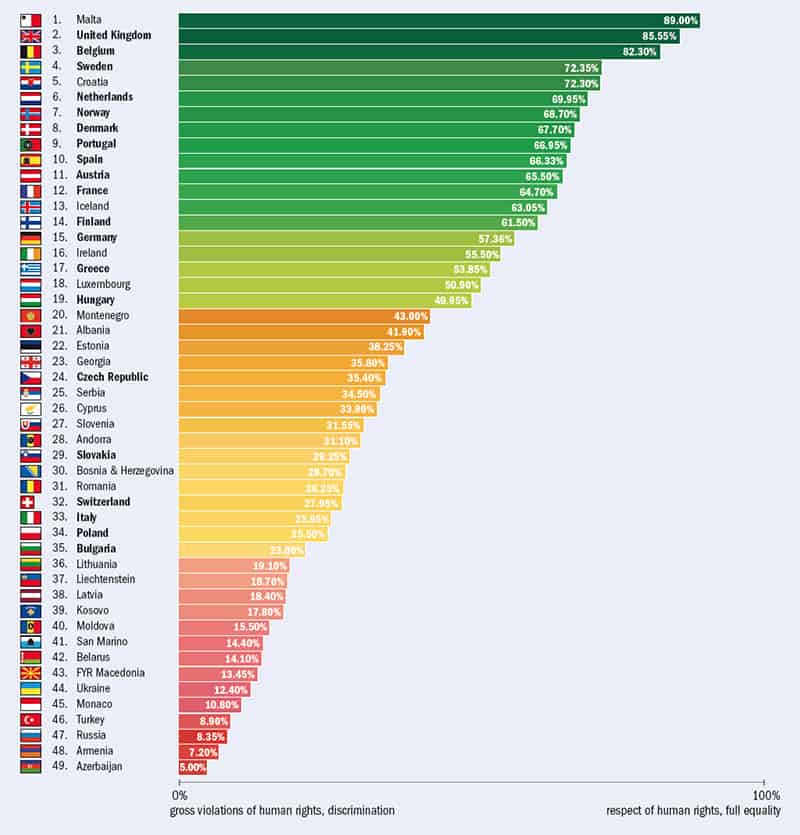

As well as providing each other with social support, LGBT CERN is also a space where members can discuss work-related issues unique to their community. For example, if a group member is offered the chance to speak at an international scientific meeting in a country, such as Russia, which has seen violent anti-LGBT attacks in recent years (see figure 1), how should they respond? While one solution would be simply not to attend the conference, turning down a speaking opportunity can count against you. You might not be offered another chance to speak for some time, hampering your career.

A shaky infancy

LGBT CERN is now a well-established group with more than 80 members. But Randle-Conde, who was chair of the club until 2013 when he took up his current position in Belgium, recalls that it had a “shaky infancy”. The first challenge was getting enough people involved. “You can’t have an LGBT group without members,” he says, “and most of the members are ‘invisible’ in the sense that unless someone identifies with a group one can’t tell if an individual is LGBT.” To raise awareness of LGBT CERN, the group put out messages via ally groups such as Young@CERN and Brits@CERN. Slowly and steadily, the membership of LGBT CERN grew. A weekly lunch meet-up at CERN’s “Restaurant 1” and bi-weekly drinks in central Geneva were established, as was a monthly DVD night that was popular with the group’s non-out members.

The next step was to get LGBT CERN recognized as an official CERN Club, of which there are now 53 including the Running Club, the WoMen’s Club (previously the Women’s Club, which was renamed to be more inclusive) and the Collectes à long terme – the “Long-term collection”, which is a CERN Staff Association programme to fundraise money for humanitarian projects. Randle-Conde says the main motivation for LGBT CERN becoming a CERN Club was that it would make the group more visible to potential members. Other benefits would include having some protection from CERN to help deal with any problems that might arise.

In early 2012 members of the LGBT CERN committee therefore contacted Rachel Bray, who leads the Clubs Coordinating Committee (CCC), but were disappointed when Bray told them it was unlikely that LGBT CERN would become an official CERN Club. Around the same time, Randle-Conde says, his group also contacted the then newly created CERN Diversity Office and met its then head, Sudeshna Datta-Cockerill, who is now the CERN ombudsperson. Randle-Conde and Datta-Cockerill have conflicting memories of this meeting. The former says that Datta-Cockerill told him there was “no space in the organization of the Diversity Office for an LGBT group”; however, Datta-Cockerill says that she thought they had some very useful and constructive discussions at the time, which contributed to a proposal that would later be implemented. Since these were face-to-face meetings, no documentation was available to Physics World to verify what was said.

Pursuing CERN Club status

Undeterred, members of the group put together a formal application to be a CERN Club and in July 2012 met the Staff Council of the Staff Association (the CCC’s parent body) to explain why it was pursuing official status as a CERN Club. After the meeting, group members left so that the Staff Council could discuss the application in a closed session, and waited to hear about the decision.

Two days later, Randle-Conde and his fellow applicants received an e-mail from physicist Michel Goossens, then president of the Staff Association, who retired earlier this year after a 36-year career at CERN mostly developing tools for scientific document handling. The e-mail acknowledged that the statutes of LGBT CERN were “compatible” with those of the Staff Association, but added that “there was a consensus to give Council more time for reflection in order to understand whether the form of a club under the aegis of the Staff Association is the best way for the LGBT community to get the visibility and representation they want”. The message went on to lay out plans to communicate with senior management “to define a common approach on the issue at hand in the framework of the Code of Conduct, and the equal opportunities and diversity policies advocated by the Organization”. This would then be reported back to the Staff Council in October.

The following month, in August 2012, an article written by CERN’s then director-general Rolf Heuer, entitled “Strength in diversity”, was posted on the CERN website. “We’re proud of our diversity at CERN, where all individuals can contribute to their full potential, without the need for groupings or associations that foster separateness,” he wrote.

In October, Randle-Conde and his fellow applicants received another e-mail from Goossens, containing a formal “position document”. In this, Goossens included the above quote from Heuer and added that this point “is important, since the Staff Association also considers that a diversity policy should not divide by fostering the emergence of interest groups or associations promoting particular communities”. He then delivered the association’s decision on whether LGBT CERN could be an official CERN Club: “taking into consideration the arguments developed previously the Staff Council decided not to recognize LGBT CERN as a ‘Club under the aegis of the Staff Association’, on the basis that it groups members of a particular community, LGBT in this case”.

To outsiders, this might all seem like a trivial matter, but it was a blow to members of LGBT CERN. “Should an organization of several thousand people from across the world seeking more social inclusion and legal protection have an LGBT group?” asks Randle-Conde, rhetorically. “I find it deeply worrying that within the Staff Association this is considered worthy debate at all, as the two sides are not equally valid or equally worthy of attention.”

Thomas Elias Cocolios, who was a research fellow at CERN when the group formed in 2010 and in 2012 went on to work as a research fellow at the University of Manchester in the UK, says that his experience as an LGBT person at CERN was positive overall, and it was only when the Staff Association’s decision was delivered that he realized how dire he felt the situation was. He points out that the LGBT community at Manchester formally organized itself at the same time as LGBT CERN started. “They have received complete support from the university leadership and the university is now a Stonewall Champion,” he says. “It is just a question of how seriously the management considers the issue.”

Another challenge for the group has been people taking down or vandalizing its posters. As well as communicating that LGBT CERN seeks to provide a welcoming space for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender individuals at CERN – with friends and allies welcome – the posters also give details of the group’s upcoming events as well as their contact details. Physics World was sent photographs of 14 LGBT CERN posters that had an offensive note attached, been covered with blank paper, been “crossed out” with red pen, had “No post here” or “Schwein!” (pig in German) written over them, had chunks ripped out or been torn off and crumpled. One photo shows an LGBT CERN poster with a printed-out message attached to it quoting the Biblical book of Leviticus: “If a man lies with a male as with a woman…they shall surely be put to death.”

Seeking solutions

Faced with the anonymous hostility represented by the poster defacements, as well as what they felt was a lack of endorsement from CERN’s Diversity Office and Staff Association, in November 2012 the members of the LGBT CERN committee sent a letter to a group of eight people – including Heuer, Datta-Cockerill and Goossens – in which they summarized the events to date and wrote that “choosing not to recognize LGBT groups is no longer seen as a neutral action in Western Europe”.

“We are very disappointed with the position of the Staff Association,” they wrote. “This ruling violates the legislation of the Council of Europe on sexual orientation and gender identity.” To support their argument they appended some passages from the Council of Europe’s adopted recommendation CM/Rec(2010)5 on measures to combat discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation or gender identity. These included the passage: “Member states should take appropriate measures to ensure…that the right to freedom of association can be effectively enjoyed without discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation or gender identity; in particular, discriminatory administrative procedures, including excessive formalities for the registration and practical functioning of associations, should be prevented and removed.”

The LGBT committee wrote that “We…would like to encourage the Staff Association and CERN directorate to revise their current position in keeping with the existing legislation and accept us alongside the other clubs. As members of the CERN community, we think it would be best for everyone if this matter is resolved internally and brought into line with the regulation of the Council of Europe.”

Shortly after sending the letter, the LGBT CERN committee was invited to meet the Diversity Office, which proposed the creation of a system of “Informal Networks” to represent the interests of different self-organized groups, and that LGBT CERN would be the first. “We were very happy with this development,” says Randle-Conde. “We got nearly all of what we asked for, but the situation will still need to change, because we will continue to be seen as separate from the clubs.” The group stuck to its guns of trying to solve the matter internally and it was only when Physics World approached the group in 2015 that it decided to speak out publicly.

Where we are now

Geneviève Guinot, who became leader of the Diversity Programme in 2014, says she believes that LGBT CERN is being appropriately supported with its recognition as an Informal Network. She says that the Clubs are created based on a particular sport, leisure or cultural activity – as opposed to individual characteristics – and that they are open to the external world, whereas the Informal Networks are not. The idea of creating Informal Networks was “to support integration at CERN and give such existing groups an ‘official’ existence at CERN”, she says, adding that there are now nationality and disability networks too. “My team also has regular meetings with the group to discuss matters of concern,” she says. Such matters have included extending the scope of paternity leave to any staff member, regardless of gender, and equal benefits for married couples or couples in a registered partnership, also regardless of gender, both of which have now been implemented at CERN.

Arnaud Marsollier, head of press at CERN, makes another point as to why LGBT CERN is not a CERN Club. He says that clubs are shaped to allow people to share passions and practise activities together in an inclusive way, avoiding, for example, political or religious groups. “LGBT is not a political or religious one, but when you open the door to different types of groups, it might be difficult not to see some kind of lobbying bodies appearing on different topics, rather than clubs to just develop leisure activities,” he says.

As for the poster defacement, Marsollier says disciplinary measures have been taken against at least one person. In addition, the issue was tackled publicly in July 2015 by Heuer. In an article published on the CERN website entitled “Our humanity at CERN”, Heuer wrote “[CERN is] a place where everyone is welcome, and where anyone can succeed, regardless of his or her ethnicity, beliefs or sexual orientation. It is therefore with some disappointment that I have learned of a spate of recent events concerning posters put up around the laboratory by our LGBT community.” He wrote that he was establishing a policy for poster use at CERN involving a series of dedicated poster display areas subject to certain guidelines. “Look out for that policy, but in the meantime, I encourage you all to show respect to your neighbours, regardless of their individual differences,” he continued. “Doing so is part of CERN’s identity. It is part of our humanity.”

According to the current chair of LGBT CERN, the group has not noticed any significant change in the rate of poster removal since Heuer’s statement. As Physics World went to press, the official poster policy had yet to be announced.

Marsollier says that CERN has made “quite significant progress” since LGBT CERN was formed in 2010 considering the “large diversity in sensitivities” at what is a large international collaboration. For many members of LGBT CERN, however, the group’s lack of Club status remains a sore point, even following the establishment of the group as an Informal Network. “As long as we have Clubs for some groups, but not for the LGBT CERN group we will be seen as different and less deserving of support by many people,” says Randle-Conde. “Most people at CERN do not even know what an Informal Network is.” An LGBT CERN member who wishes to remain anonymous expresses a similar sentiment: “The unequal (though improving) treatment of the LGBT CERN group is evidence that CERN still has a long way to go in accepting LGBT people,” he says.

- Enjoy the rest of the March 2016 issue of Physics World in our digital magazine or via the Physics World app for any iOS or Android smartphone or tablet. Membership of the Institute of Physics required