Einstein’s Masterwork: 1915 and the General Theory of Relativity John Gribbin 2015 Icon Books £10.99hb 240pp

On 25 November 1915, as devastating war raged throughout Europe, Albert Einstein presented the paper Die Feldgleichungen der Gravitation (“The field equations of gravitation”) to the Prussian Academy of Sciences. This paper, the last in a series of four, marked the first consistent formulation of his general theory of relativity, a task that had challenged Einstein for almost a decade. The golden goose of theoretical physics, enticed to Berlin in 1914, had delivered a priceless egg.

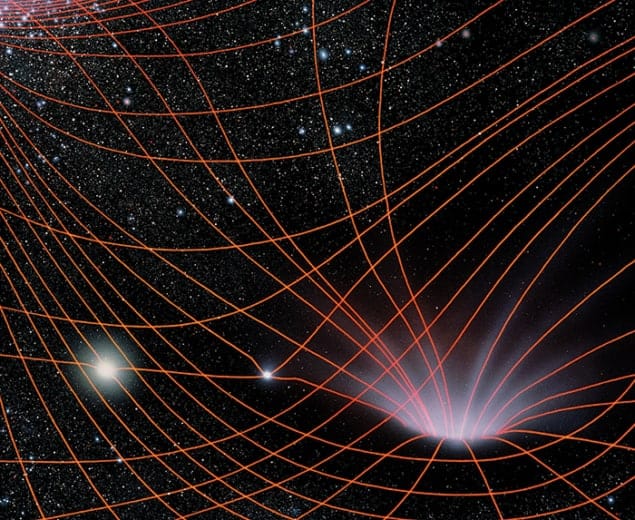

Among physicists, the general theory is regarded as Einstein’s greatest work – the masterpiece that surpasses even his ground-breaking papers of 1905 on the atomic hypothesis, the light quantum and special relativity. Indeed, the general theory has long been considered one of the great triumphs of 20th century science, a tour de force that remains unsurpassed in terms of its originality, profundity and predictive power. By replacing Newton’s “action-at-a-distance” law of gravity with a revolutionary new view of gravity as a curvature of space–time, Einstein laid the foundations for our modern view of the world on the largest scales, from our understanding of black holes to the Big Bang model of the evolution of the universe.

In his 1905 theory of relativity (later named the “special theory”), Einstein’s insistence that the laws of physics must appear identical to observers in uniform relative motion led to the prediction that space and time are neither independent nor absolute. Instead, observers travelling at high speed relative to one another would experience a given interval in space and time differently. Long before this startling prediction could be verified by experiment, Einstein had embarked on the quest for a more universal theory of relativity – that is, a theory that could describe bodies in non-uniform (accelerated) motion. Anxious that the new theory would also include gravitational effects, he realized to his delight in 1907 that these two ambitions were one and the same. This great insight – the equivalence principle – set Einstein on the long and difficult road to the general theory of relativity.

In Einstein’s Masterwork: 1915 and the General Theory of Relativity, John Gribbin provides a timely, succinct and highly accessible account of -Einstein’s greatest theory and its legacy today. A visiting fellow in astronomy at the University of Sussex, Gribbin is best known as a science writer of prolific output. Earlier titles include popular histories of modern science (Science: a History), quantum theory (In Search of Schrödinger’s Cat) and cosmology (In Search of the Big Bang), as well as several scientific biographies.

Here, he turns his attention to the story of general relativity, which he tells in the context of Einstein’s life and work before and after 1915. This is a logical approach in many ways. Apart from creating a narrative that is eminently readable, the science is presented in historical context in a manner that makes it easy to absorb.

For example, having described Einstein’s early life and undergraduate years, Gribbin discusses his early research in statistical mechanics. This work is often overlooked in popular accounts, but it set the foundations for Einstein’s pioneering papers of 1905. Similarly, the author explains how Einstein could not progress beyond his equivalence principle before the advent of Hermann Minkowski’s geometrization of special relativity – or before he had acquired sufficient mastery of differential geometry to apply -Minkowski’s approach to curved geometries.

Einstein’s long road to general relativity has been the subject of much research in recent years by Einstein scholars such as John Stachel, Don Howard and Jürgen Renn, and accounts of the story have been given at a popular level in books such as Amir Aczel’s God’s Equation, Jean Eisenstaedt’s The Curious History of Relativity and Pedro Ferreira’s The Perfect Theory. Gribbin carves his own place in this literature; while his narrative is less detailed than that found in any of the books above, it deftly conveys the main points in Einstein’s journey to the general theory in characteristically clear and succinct prose.

It must be admitted, however, that in placing the story of general relativity in the wider context of Einstein’s life and work, the author risks telling a tale that has been told many times before, not least in a plethora of Einstein biographies. Indeed, there is considerable overlap with the author’s own 1993 book Einstein: a Life in Science, co-authored with Michael White.

This is no great problem in principle, due to the freshness of the writing and the author’s uncanny ability to convey profound scientific concepts in a few crisp sentences. However, there are undoubtedly times when the book feels more like a biography of Einstein than a biography of his greatest theory.

For example, the chapter that deals with the legacy of general relativity (from classic observational tests to the foundational role of the theory in modern astrophysics and cosmology) is curiously short, and is followed by a chapter describing Einstein’s life and science in his later years. It seemed to this reviewer that the “legacy” section would have worked better as the last chapter and could have been more substantial.

In particular, Gribbin’s discussion of the evolution of relativistic cosmology is extremely brief, given the central importance of general relativity in modern cosmology. While the “static” cosmic models of Einstein and Willem de Sitter are fleetingly mentioned, there is no discussion of Einstein’s resistance to the time-varying cosmologies of Alexander Friedmann and Georges LemaÎtre- when they were first proposed (and no distinction is drawn between their very different approaches). The author also fails to distinguish between LemaÎtre’s 1927 model of cosmic expansion and his later hypothesis of an origin for the universe, and there is no discussion of Einstein’s conversion to time-varying models of the cosmos in the wake of Edwin Hubble’s observations of the galaxies. These omissions are a pity, as recent research has shown that Einstein’s cosmology offers many insights into his thoughts on both relativity and relativistic cosmology.

It is also puzzling that Einstein’s great search for a unified field theory is mentioned only very briefly, given the central role of general relativity in this long quest. As many science historians have noted, it was the great success of Einstein’s geometrical approach to general relativity that laid the foundation for his unshakeable conviction that the road to unification lay in further generalizations of the field equations (a conviction that was shared by Erwin Schrödinger). Finally, I found the author’s objection to the shorthand term “general relativity” somewhat ahistorical and was disappointed that the famous field equations Gμν = – κTμν were never shown.

However, these are minor criticisms that should not deter the reader from this excellent and informative book. Einstein’s Masterwork is a beautifully written and highly accessible account of the genesis of a great theory, a hugely enjoyable read that is highly recommended for physicists and the public alike.

- Enjoy the rest of the August 2015 issue of Physics World in our digital magazine or via the Physics World app for any iOS or Android smartphone or tablet. Membership of the Institute of Physics required