Scientists who crave the recognition that comes from publishing important papers need to embrace some harsh realities if they also want to make money by commercializing their research. Business adviser Neil Kane explains how to overcome this apparent dilemma

“I wish someone would just give us five million dollars and leave us alone.”

Those words were recounted to me by a distinguished scientist at a national laboratory in the US who had a technology that I was helping to commercialize. I replied by explaining that if we did find someone who was willing to give us five million dollars, he (the scientist) should be prepared to give up 80% of his company in return. A discussion followed, he harrumphed a bit, and I tried to explain how venture economics works. Failing to make my point, I concluded the conversation by saying that even if we did find someone prepared to hand over the money, they sure as heck wouldn’t leave us alone.

My consulting work over the past few years has mainly involved helping universities and federal labs to form businesses around their technologies. I have been the “business guy”, working with teams of scientists and academics to develop technologies that may (or may not) have commercial potential. As a result of my interactions, I have uncovered

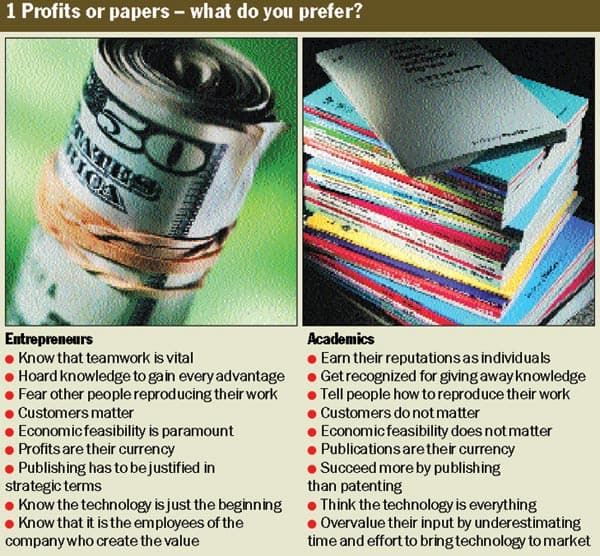

a number of differences in perspective – cultural issues, if you will – between the way that academics and entrepreneurs think. I have coined the phrase “rich or famous?” to describe the tension that exists between creating a successful commercial product (i.e. being rich) and developing the best possible technology just for the sake of it (i.e. being famous). Let me explain.

Different perspectives

Academics make their reputations based on what they know. They do not “profit” from this knowledge until they publish it and can explain to others how to reproduce their work. Only then is their professional reputation enhanced. Publication success is often a key factor in deciding whether an academic wins research grants or is offered a tenured post at a university. For many academics the recognition they gain by advancing knowledge in their field is sufficient. But they will not see a meaningful financial reward for their work unless it is commercialized, usually by founding a successful business. And, with very few exceptions, successful businesses do not get created unless an academic teams up with an experienced entrepreneur.

Business people and entrepreneurs have very different incentives and perspectives from academics (see figure 1). Business people do not profit from their work until they create something that has commercial value, which often comes from exploiting privileged information. The best entrepreneurs I know are not concerned about getting credit for their ideas – the financial pay-off is reward enough. The typical behaviour of an academic – “Let’s publish!” – is the exact opposite of what one would want if the same technology were developed inside a commercial organization.

However, the pursuit of money by business people is often repugnant to dyed-in-the-wool academics, especially if it requires protecting, and not revealing, information. Filing for patent protection is one way to bridge this gap. Information can then be disseminated and maintained for the exclusive use of the patent holder. Generally, though, patents need to be filed before publication.

The real world

In my experience, the process of starting a business usually throws academics far outside their comfort zone. It is a very unsettling feeling to have the fate of one’s technology put in the hands of someone else. Scientists tell me it is like putting your child up for adoption. This loss of control is a great obstacle to making progress because, to alleviate their anxiety, scientists often make decisions that are counter-productive.

For example, researchers who have already begun the process of commercialization are often reluctant to give up a meaningful slice of their company to their investors or management team, even though wealth can only be created by bringing in new resources and using the talent of other people. Scientists prefer instead to take whichever investment offer dilutes their ownership the least, even if it is unlikely to maximize their earnings in the long run. Having seen this issue cause great harm on several occasions, I currently tell scientists to find a trusted advisor who can help set their expectations appropriately and assure them that they are not being taken advantage of. This is as true for new fields like nanotechnology (see figure 2) as it is for more traditional research areas.

Scientists habitually overvalue their technology because they do not appreciate the time and money needed to turn it into something that can be profitably offered for sale. One of my clients, for example, developed a hardness coating that could extend the life of rotating machinery. The scientists had developed a prototype that they had tested in the laboratory, which performed wonderfully for three weeks. Sensing a purchase order was right round the corner, they formed a business to commercialize the technology.

But when my firm got involved to help craft a business strategy, write a business plan and raise venture capital, we discovered that – according to industry practice – such coatings have to be subjected to extended wear-testing for at least 2.5 years before they are even allowed to be sold. That is over 160 times longer than the original lab tests – and at the time our client did not even have the foggiest notion of what it would cost to produce.

People build businesses

We often ask our clients if they are governed by the laws of gas dynamics or the laws of competitive dynamics. By assembling a great team of people you can often give yourself a competitive advantage in the marketplace. But if your technology strategy depends on violating the laws of nature, you have got a big problem.

I remember once talking to my high-school physics teacher, who had been a leading educator in our district for decades.

“Don’t you get tired teaching physics?” I asked him one day.

“I don’t teach physics,” he replied. “I teach students.”

The same wisdom applies to securing financing for start-ups: investors do not fund technologies, they fund people. That is possibly the most important point to take away from this article. The corollary is that companies do not bring technologies to market, they bring products to market.

If you form a company, the business will take on the priorities and goals of the people who put in the money, not the people who contribute the technology. As Kenneth Suslick, a chemistry professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and founder of ChemSensing Inc, says “Control equals capital. If you want capital, then you must yield control. Academicians, alas, are control freaks.”

How mature your technology is will be reflected in the valuation you receive from your investors. That is how the merits of technology are calibrated. While it is almost always better to have patents than not to have them, the existence of patents does not necessarily make a business. Patents tend to be positioned on the low end of the valuation scale, much to the disappointment of the scientists, particularly if much development work lies ahead or if the markets for the technology are not yet mature.

In all of the companies that I have seen become successful, the venture capital arrived with the management team, not the technology. But even outstanding management teams need a technology platform on which to build.The scientists need management, and vice versa.

Working together

So are scientists capable of abandoning their natural tendencies to publish and instead become filthy rich? Can entrepreneurs build great businesses while being honourable stewards of the underlying technology? Yes, but both sides need to understand each other’s motives and recognize the contributions that each party brings to the table.

Scientists who fancy themselves as business people often make elementary mistakes such as evaluating investment offers based on the highest valuation. Similarly, business people who alienate the technical team are also in for trouble – because technology obviously dominates the early days of a business, long before it has any power in the market. So both parties need one another.

Scientists who found companies can be both rich and famous, but having one’s cake and eating it requires working with the business team empowered to run the company. Without good two-way communication, an already challenging endeavour becomes nearly impossible. If you do take the plunge, keep the following points in mind.

i) Entrepreneurs and scientists need to understand each other’s motives and incentives;

ii) venture capital arrives with the management team, not the technology;

iii) scientists need trusted advisors;

iv) you can be famous but not rich, but if you are rich enough, you will be famous;

v) nothing rewards scientists like having their technology become ubiquitous;

vi) scientific exploration with an eye toward commercialization is permissible;

vii) giving away information helps no one;

viii) communication is paramount;

xi) without a profit motive, nothing will get manufactured, and there is no wealth creation until something is sold.