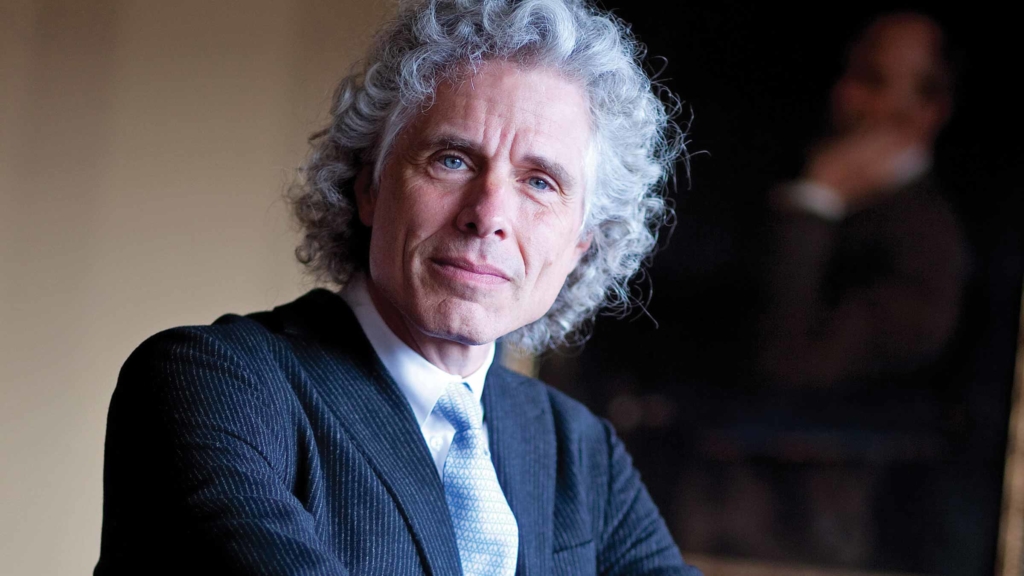

Steven Pinker may be a talented scientist, but he abuses the humanities, argues Robert P Crease

Are you incensed when Deepak Chopra, the US alternative-medicine advocate, promotes “quantum healing”? Are you infuriated by people throwing around abstract concepts like relativity, energy and evolution without understanding what they mean to scientists? Then you may understand how I feel when scientists make ignorant assertions about philosophy and the humanities.

My current source of annoyance is Enlightenment Now: the Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress – a new book by the Harvard University cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker. Life is wonderful, Pinker says, and claims he has data to show it. The book has more than six dozen graphs demonstrating that good things such as life expectancy, literacy, income, education, human rights, leisure time and tourism are on the way up, and that bad things such as wars, violence, poverty, crime, disease, plane crashes and death by lightning are on the way down.

A “war on science”?

The chief menace Pinker sees in the modern world is an “intellectual war on science” that is “wreaking havoc in universities and jeopardizing the progress of research”. The rightful rule of “Enlightenment optimists” like himself, Pinker says, is threatened by anti-science “Romantic declinists”, whose leaders are philosophers such as Nietzsche, Heidegger, Foucault and Derrida.

Imagine that! Four dead white males, one of them long gone from this planet, are leading an army of humanists that threaten to bring down science! Pinker’s on shaky ground, however, given that scientists like him get by far the lion’s share of grant money and public adulation. His ground is even shakier given that he reveals he knows as much about what these four said as Chopra does about quantum mechanics.

Let me give just one example. Pinker claims Nietzsche recommended that people become – he’s quoting Nietzsche now – “hard, cold, terrible, without feelings and without conscience, crushing everything, and bespattering everything with blood”.

You can hardly get Nietzsche more wrong. Pinker plucks these words from Nietzsche’s book On the Genealogy of Morals. Published in 1887, it is, as its subtitle suggests, a polemic (ein Streitschrift). Polemics, especially by authors who are well known for their use of metaphor, irony and hyperbole, cannot be read as if they were conventional journal articles. As the philosopher Robert Scharff likes to say, one might just as well cite the famous beginning of The Social Contract (“Man is born free…”) to mock Jean-Jacques Rousseau for believing that everyone is walking around wearing chains.

Humanities scholars like to read carefully and know context is important. Pinker’s lifted phrase comes from the 11th section of the first essay of The Genealogy. Nietzsche, a philologist by training, is scrutinizing the origins of the concepts of “good” and “bad”. He notes that the masters and cultural victors – the top 1%, we would say – are likely to have one understanding of these concepts; the oppressed and cultural losers another.

As an example, he cites the Greek epic poet Hesiod’s classification of history chronologically into five Ages of Man. Two of these ages are actually the same age, Nietzsche says, but one represents the perspective of the winners, the other of the losers. Hesiod’s “Heroic” age is the world seen from the perspective of the likes of the heroes of Thebes and Troy, while the “Iron” (Erz) age is that world as seen from the perspective of “those who have been crushed, despoiled, brutalized, sold into slavery.” That latter age, Nietzsche writes, is the one with leaders whose actions are “hard, cold, terrible”, and so forth.

Nietzsche is not recommending we behave the way the wretched see their oppressors acting. Nor is he saying the two perspectives are equal. He is holding up a mirror to the conventional Christian morality of his time, trying to jolt readers into reflecting on its impact on their lives. Nietzsche is also showing that, if you simply banter about abstractions without connecting them to the life source from which they arose, you can say anything you damn well please, because you have lost track of life itself. You can say the world is terrific or terrible, depending on your perspective.

It’s ironic that Pinker has misunderstood a passage in which Nietzsche was illustrating the misleading use of abstractions.

Robert P Crease

It’s ironic that Pinker has misunderstood a passage in which Nietzsche was illustrating the misleading use of abstractions. For one can imagine an anti-Pinker writing a book packed with graphs illustrating the rise of inequality between rich and poor, numbers of refugees, data breaches, industrial-scale political lying, mass shootings, genocide and so on. Such graphs would not capture the world as seen from the privileged perch of a tenured position at Harvard. Yet the fact that abstractions can channel privilege or oppression is not the worst of it. Nietzsche’s point is that when we live by abstractions, we forget how we live. Using only psychological theories to, say, guide our behaviour towards others, we forget what human relationships are.

What philosophers do

In Pinker’s case, the forgetting is coupled with a false confidence that expertise in one thing makes you an expert in everything, such as how to read Nietzsche. Later in his book, Pinker quotes more passages from Nietzsche and labels them “genocidal ravings”. He’s culled these passages from secondary sources. To understand them in context, you’d have to learn how to read a brilliant writer who uses metaphor and irony to connect and transform people in ways that literal language does not. That would require taking a humanities course. And if you can read better, you can appreciate many things better, including the value of science.

The critical point

Thank you, Steven Pinker, for showing the harm when scientists don’t take enough humanities courses. A humanities education helps provide a deeper grip on one’s experiences and on the world in ways other than through graphs and abstractions. Isn’t it more likely that the very lack of humanities education is what fosters thoughtless about the world and the dangerous sway of science denial today?

- Enjoy the rest of the May 2018 issue of Physics World in our digital magazine or via the Physics World app for any iOS or Android smartphone or tablet. Membership of the Institute of Physics required