Amara Graps is a planetary scientist and space entrepreneur in Riga, Latvia. This post is part of a series on how the COVID-19 pandemic is affecting the personal and professional lives of physicists around the world. If you’d like to share your own perspective, please contact us at pwld@ioppublishing.org.

Since 10 March 2020, when Latvia went into lockdown, my 11-year-old daughter Vija has attended only 16 in-school sessions. It’s an understatement to say that my work as a space entrepreneur and senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute and the University of Latvia has been impacted. I am a solo parent, and I never imagined that I would become a many-hours-per-week teacher. But while it’s not strange these days for kids to do distance learning, it is a little bit strange for children like my daughter to be learning remotely while their friends are in class – as was the case for most of this autumn.

The story of how this happened is both complex and sobering. Within two weeks of Latvia’s spring lockdown, teachers were augmenting existing electronic course materials. With broadband speeds among the best in the world – including in the countryside, where many Latvians rode out the first wave – “online everything” was relatively easy. Thanks to this and the cohesiveness of Latvian society, our management of the first wave of the pandemic was among the best in Europe. In the summer, the Latvian Investment Agency even trumpeted the country’s achievements with a series of promotional videos entitled Ahead of the Curve.

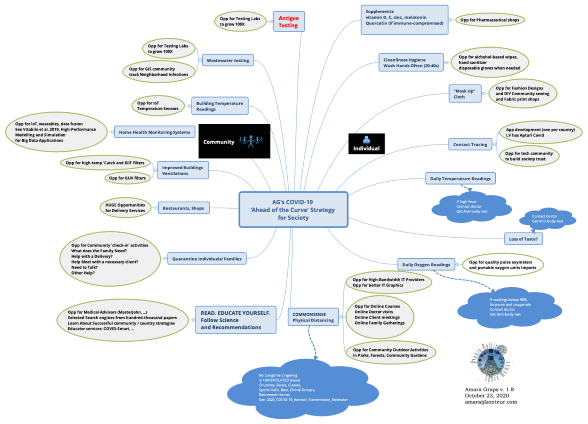

They weren’t the only ones who were optimistic. I was, too. I filled pages in my journal and created elaborate mind maps, brainstorming ways to fight the disease and improve society. Because countries all over the world were experiencing disruptions, formerly siloed groups had an incentive to listen to each other and think creatively about solutions. I cherished, especially, the Foresight Institute’s “Global Online” discussions, which took place every night at 9 p.m., Riga time, for about six weeks.

Causes for concern

From these discussions, though, I also picked up medical information about the virus that made me concerned – first for myself, a person in her late 50s who had major surgery in January, and then for my daughter, who has allergies that neither I nor her doctors fully understand. It seems that Vija may have something called mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), which has implications for her COVID-19 risk; a leading MCAS researcher has said that some of the most severe COVID-19 infections may be rooted in undiagnosed MCAS-like conditions. This information made me extra cautious about returning her to school in the autumn, when in-person classes were due to resume.

While I was immersed in learning more for my family’s health, Latvia had a lovely, long and relaxed summer – as long as one didn’t think about the pandemic. Latvia and the other Baltic countries, Lithuania and Estonia, formed a “Baltic Bubble” to facilitate summertime travel without quarantine or isolation. People had parties. Restaurants and gyms reopened. No-one wore masks. Social distancing disappeared. And parents who hadn’t coped well with distance learning in the spring – either because having kids at home made it challenging to manage their own work, or because they didn’t have the electronic devices they needed for their kids to follow online courses – lobbied the government to keep schools open in the future, no matter what. Faced with their strong opinions, the education minister agreed.

In the meantime, the rest of the government acted as if its pandemic work was finished. Our main infectious disease expert, who was on our airwaves constantly in the spring – explaining the science, the what, the how and the why – faded into the background. He and the experts who followed him spoke of the need to prepare for a second wave, but at the government level no serious preparations were made. And thanks to the relative ease with which our country “flattened the curve” in the spring, with minimal impact on the medical system and few deaths, disinformation and disagreement entered our formerly cohesive society.

Falling behind

The most vocal and proud among this dissenting faction stated that Latvians lived through three military occupations in the last century. Why should we be scared of a virus? People began to say that we had “done enough” already, and that masks and social distancing were not necessary. A split formed between native speakers of Russian and Latvian about the virus’s risks. Conspiracy theorists even claimed that COVID-19 was created in the US to further Bill Gates’ business interests, then brought to China during a military sports competition.

By August, infection numbers were creeping up due to holes in the “Baltic Bubble” and, later, to traditional singing excursions that proceeded without restraint. Still, schools opened on 1 September, and my daughter’s large government-funded school was among them, complete with a hand sanitizer machine at the door and a plan for pupils to spend four days a week in school and one day at home, to approximate a separation strategy. The school also provided an elaborate flu/COVID-19 symptom flowchart describing when to keep a child at home.

Yet inside my daughter’s classroom, kids were not separated by large distances. The windows were not opened regularly. Neither teachers nor students wore masks. Kids were not encouraged to wash their hands regularly. And so the super-spreader events began.

Two and a half weeks into the new semester, a bad (but normal) flu passed through Vija’s classroom. We were both ill for two weeks – an experience I considered a warning. In the next few days, my concern grew. As we were recovering from this normal flu, the novel coronavirus rode into Vija’s school on its tail. A singing excursion that a couple of the teachers took in September ended up infecting nearly half of their 60 colleagues, who tested positive in the first week of October. From there, the disease spread to students, siblings and parents. Eventually, the cluster grew to 150, including 14 of the 29 students in my daughter’s class. We thought we might be among them, especially after our cat had some symptoms (yes, cats can catch COVID-19), but on 12 October our tests came back negative. We had dodged a bullet.

Lessons (not) learned

With Vija’s school quarantined in late October and early November, a few teachers in the hospital, and a high prevalence of the virus in Latvia’s capital, Riga, I felt sure that the principal would implement distance learning. But when they polled the parents, two-thirds voted to send the younger kids back to school, overruling the rest of us. So I chose to keep my daughter at home while her classmates continued attending – until 7 December, when the Latvian government finally bowed to the inevitable, and ordered all schools to implement distance learning again.

Physics in the pandemic: ‘This coronavirus has created an employment crisis across the country’

In the past nine months, I have gone from feeling safe and happy in Riga to feeling as though people in my town want my daughter and me to die of a preventable disease. Yes, that is an exaggeration – but my winter solstice in Latvia will nevertheless be a time of reflection and emotional transition. If Latvian society follows the rules currently in place, we should be on the other side of the second-wave peak by late January 2021, with vaccinations planned to start in February. Yet the main thought on my mind is this: if the Baltic nations cannot manage a small crisis like this pandemic, what does that say about the looming existential crisis of climate change?