Glass may look just like a normal solid, but at the microscopic level it behaves in surprisingly complex ways

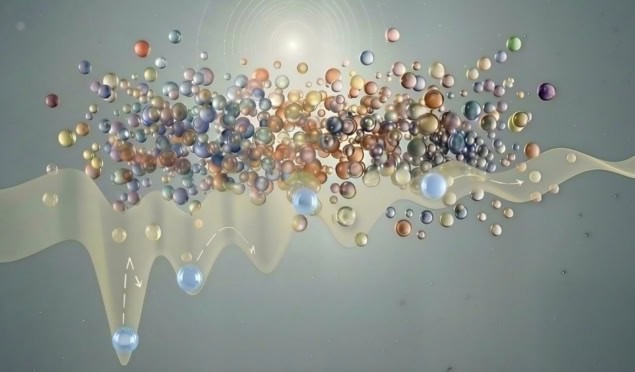

Unlike crystals, whose atoms arrange themselves in tidy, repeating patterns, glass is a non‑equilibrium material. A glass is formed when a liquid is cooled so quickly that its atoms never settle into a regular pattern, instead forming a disordered, unstructured arrangement.

In this process, as temperature decreases, atoms move more and more slowly. Near a certain temperature –the glass transition temperature – the atoms move so slowly that the material effectively stops behaving like a liquid and becomes a glass.

This isn’t a sharp, well‑defined transition like water turning to ice. Instead, it’s a gradual slowdown: the structure appears solid long before the atoms would theoretically cease to rearrange.

This slowdown can be extrapolated and be used to predict the temperature at which the material’s internal rearrangement would take infinitely long. This hypothetical point is known as the ideal glass transition. It cannot be reached in practice, but it provides an important reference for understanding how glasses behave.

Despite years of research, it’s still not clear exactly how glass properties depend on how it was made – how fast it was cooled, how long it aged, or how it was mechanically disturbed. Each preparation route seems to give slightly different behaviour.

For decades, scientists have struggled to find a single measure that captures all these effects. How do you describe, in one number, how disordered a glass is?

Recent research has emerged that provides a compelling answer: a configurational distance metric. This is a way of measuring how far the internal structure of a piece of glass is from a well‑defined reference state.

When the researchers used this metric, they could neatly collapse data from many different experiments onto a single curve. In other words, they found a single physical parameter controlling the behaviour.

This worked across a wide range of conditions: glasses cooled at different rates, allowed to age for different times, or tested under different strengths and durations of mechanical probing.

As long as the experiments were conducted above the ideal glass transition temperature, the metric provided a unified description of how the material dissipates energy.

This insight is significant. It suggests that even though glass never fully reaches equilibrium, its behaviour is still governed by how close it is to this idealised transition point. In other words, the concept of the kinetic ideal glass transition isn’t just theoretical, it leaves a measurable imprint on real materials.

This research offers a powerful new way to understand and predict the mechanical behaviour of glasses in everyday technologies, from smartphone screens to industrial coatings.

Read the full article

Order parameter for non-equilibrium dissipation and ideal glass – IOPscience

Junying Jiang, Liang Gao and Hai-Bin Yu, 2025 Rep. Prog. Phys. 88 118002