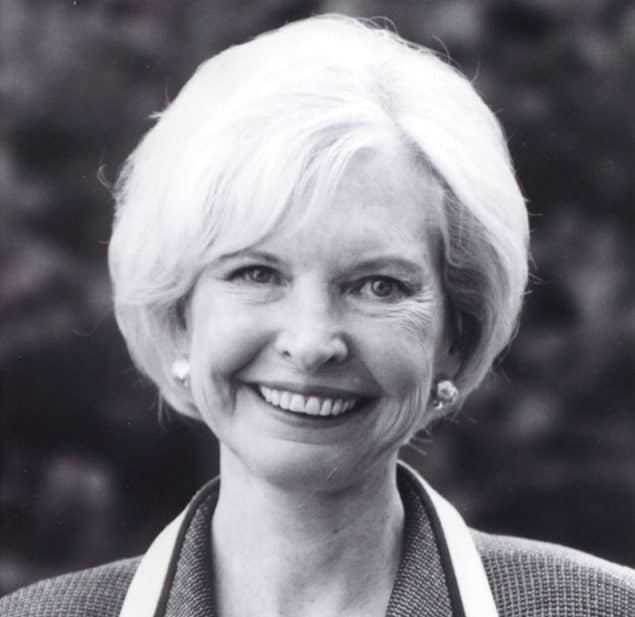

Janet Guthrie entered the history books in 1977 when she became the first woman to earn a starting spot in the Indianapolis 500 and Daytona 500 road races. Before that, she worked as a physicist in the aerospace industry. She speaks to Margaret Harris about life in the fast lane

How did you get into physics?

I started flying at a very early age. I was putting flying time in my logbook when I was 13, and made a parachute jump when I was 16, but back then a woman couldn’t fly for the military or the airlines, so instead I decided to study aeronautical engineering. But then I spent my freshman year at the University of Michigan drawing pictures of the threads on screws and mixing up batches of concrete, which really wasn’t what I had in mind, so I switched to physics. That was a much better fit. The beauty of it just entranced me – I’ll never forget deriving Maxwell’s equations, and the elegance and inevitability of them.

How did you get interested in racing?

After I graduated in 1960 I went to work in the aerospace industry, and I almost bought a half-share of an aeroplane. But there was no place in the area (this was on Long Island, near New York City) where I could go and have fun with it, and I needed a car, so I bought a 1953 Jaguar XK120 M coupé instead. That was the watershed. I started doing solo competitions – called gymkhanas at the time – in the car I drove to work every day. Oh, the Jaguar! So beautiful, so prone to breakdowns! My heart still goes pit-a-pat whenever I see one of them, that first XK120 M. Then in 1963 I bought an XK140 that had been set up for racing and took it to the Sports Car Club of America’s Driver’s School.

You also applied to be an astronaut.

Yes. By that time I’d been working in the aerospace industry for four or five years, and I was sort of a junior-grade all-purpose physicist; if we got something that nobody knew anything about, I would go down to the library and become the instant expert in it. One day a co-worker showed me a magazine article about NASA’s scientist-astronaut programme and said, “Look at this – you fit all these requirements with the possible exception of where it says ‘PhD or equivalent experience?'”. I thought, “Oh wow – the most exciting adventure of the 20th century!” So I applied, and I got through the first round before I was eliminated in the second – presumably because I didn’t have a doctorate, but one doesn’t know.

How did you get to the Indianapolis 500?

I spent 13 years building my own engines, supporting my racing with my salary as an engineer and sleeping in the back of my tow car. I won my class a couple of times at the 12 Hours of Sebring manufacturers’ championship race, but by 1975 I had reached the end of my rope. I was out of money and my career in physics was basically down the tubes; at one point I had started a Master’s degree in physics, but then it got to be spring and I needed to build an engine, which conflicted with final exams, so I took an “incomplete” in 1964 and that was the end of that. Then, at that 1975 nadir, somebody I’d never heard of called me up and asked if I’d like to take a shot at the Indianapolis 500. Well – yes! Back then, any racing driver would have given their eyeteeth for that. I was eventually successful in qualifying, and that led to a ride in NASCAR’s top series as well, so in 1977 I became the first woman to earn a starting spot in the Indianapolis 500 and also the Daytona 500.

What was the biggest challenge you faced?

Finding the money to get it done with, no question – nothing else even comes close. In 1976, of course, there was this great uproar about how having a woman on the track was going to result in the deaths of the other drivers and all that kind of thing. But once the drivers realized that I knew what I was doing and could give them some good competition – and that I was a clean driver – then all that calmed down. It was just a matter of their gaining the experience in running against me. But finding the money to get good equipment was impossible or close to it.

What are you working on now?

Not much! I wrote a memoir that was published in 2005 and I was inducted into the International Motorsports Hall of Fame in 2006, which was quite a thrill. And I still hike in the mountains here in Colorado, where I live. I’ve quit skiing, though – I’m not willing to go out on the mountain and subject myself to getting hit by a snowboarder. Being 75 sort of gets your attention. One doesn’t bounce quite so well at this age.

Skiing, flying, racing – what gave you this love of adventure?

Oh, I was born that way. I think it’s just in some people’s nature to want to find out what it’s like out there at the edge of human capabilities, and fortunately I was born in the machine age when broad shoulders and big muscles didn’t make that much difference – didn’t make any difference, in fact.