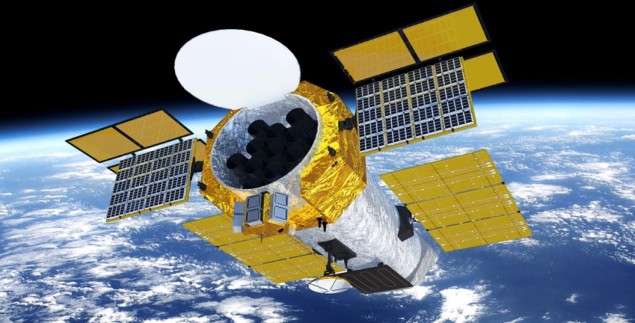

China is planning to build a next-generation X-ray observatory that will study some of the most violent objects in the universe such as black holes, neutron stars and quark stars. The enhanced X-ray Timing and Polarimetry mission (eXTP), which is estimated to cost about three billion yuan (£340m), will be launched by 2025 and involve collaboration with European scientists.

At a kick-off meeting on 2 March held in Beijing at the National Space Science Center, the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), CAS vice president Bin Xiangli put his support behind the mission noting that it should become “China’s flagship science satellite”. The mission team will now spend the next couple of years finalizing the design before building a prototype by 2022. “As we only have seven years to go it sounds like mission impossible,” says Xiangli. “But we will coordinate international efforts and deliver it without delay.”

Dedicated to space research

X-rays are the perfect tool to study objects under extreme conditions. By measuring the electromagnetic fields in and around these objects over time, scientists expect to investigate how black holes spin and determine the “equation of state” for neutron stars. Using both focusing and collimating technologies, eXTP will study the details of these X-ray sources in the energy range 0.5-30 keV. It will be carry four instruments: the Spectroscopic Focusing Array; the Polarimetry Focusing Array; the Large Area Detector (LAD); and the Wide Field Monitor (WFM).

As a next-generation observatory, eXTP will have a total collecting area of 4.5 m2, which is crucial for precision measurements. Its focusing array, for example, will have a collecting area three times that of Europe’s XMM-Newton probe. eXTP will also be able to measure the polarimetry of the sources to collect information about the various asymmetries at, or near, the surface of black holes and neutron stars.

eXTP will be an example of large technical and engineering collaboration mission between Europe and China

Andrea Santangelo, University of Tübingen

China is a newcomer in X-ray astronomy and space science. The Hard X-ray Modulation Telescope (HXMT) – the country’s first and only X-ray satellite – was sent into orbit last June and is now taking data. Before 2015, China did not have a single satellite in orbit that was dedicated to space-based fundamental research. However, with the support from the Chinese government, the country is making big leaps forward having recently launched a number of small missions such as the Dark Matter Particle Explorer or Quantum Experiments at Space Scale.

Chinese leadership

eXTP will be the most expensive space-science satellite China has ever approved costing three times as much as an average Chinese mission. According to physicist Shuangnan Zhang, principal investigator of eXTP from the Institute of High Energy Physics in Beijing, about two-thirds of the cost will come from China with the remainder made up of “in-kind” contributions from the European members and the European Space Agency. The two focusing arrays will be mainly developed in China, while LAD will be built in Italy and WFM in Spain and Denmark.

China launches X-ray telescope

“Our goal is to fly a truly large, flagship mission for astrophysics in the next decade,” says Andrea Santangelo from the University of Tübingen in Germany, who is eXTP’s international coordinator. “eXTP will be an example of large technical and engineering collaboration mission between Europe and China under the leadership of China.” Indeed, he sees no major technical problem for the eXTP to overcome. “The mission’s technical readiness is really high,” he says. “And I’m not really worried about the timeframe. China has shown its ability to keep the schedule,” he added.

Paul Ray, an astrophysicist at the US Naval Research Laboratory, notes that recent advances in solid-state X-ray detector technologies have facilitated new mission concepts. He is principal investigator of STROBE-X – a similar proposed X-ray mission that will feature a large collecting area and wide-sky coverage and that could be launched in the late 2020s, if approved. “These missions will be critical in the era of time-domain astronomy and will be an essential complement to optical, radio, and multi-messenger studies of the most dynamic and energetic processes in the cosmos,” says Ray.