What would life on our planet be like if the Moon were to vanish; or perhaps if we had multiple moons? Earth wouldn’t be the same without its constant lunar companion, as Ethan Siegel explains

Look up at the heavens after the Sun goes down, and one object in the Earth’s night sky will outshine all the others combined: our Moon. Although traditional stories ascribe many human and animal behaviours to the Moon – such as “lunacy”, nighttime howling and even menstrual cycles – those have long been debunked by science. Still, the Moon is much more than a pretty light in the sky, and is responsible for many phenomena beyond the tides. Predating humanity by some 4.5 billion years, our giant lunar companion is almost as old as the solar system itself. Without it, planet Earth just wouldn’t be the same.

When our solar system first formed, our infant Sun was surrounded by a collection of gas and dust: our protoplanetary disc. As gravitation worked to clump that matter together and grow it into planets, radiation from our star worked against us, blowing much of that material back into interstellar space. In the aftermath of our chaotic infancy, a system of spinning planets and smaller bodies remained, all orbiting the Sun in a great gravitational dance. Over time, they pushed and pulled on each other, with some objects migrating and others getting kicked out entirely. Eventually, the remaining survivors evolved into the configuration we recognize today, giving us our eight major planets.

Giant impact

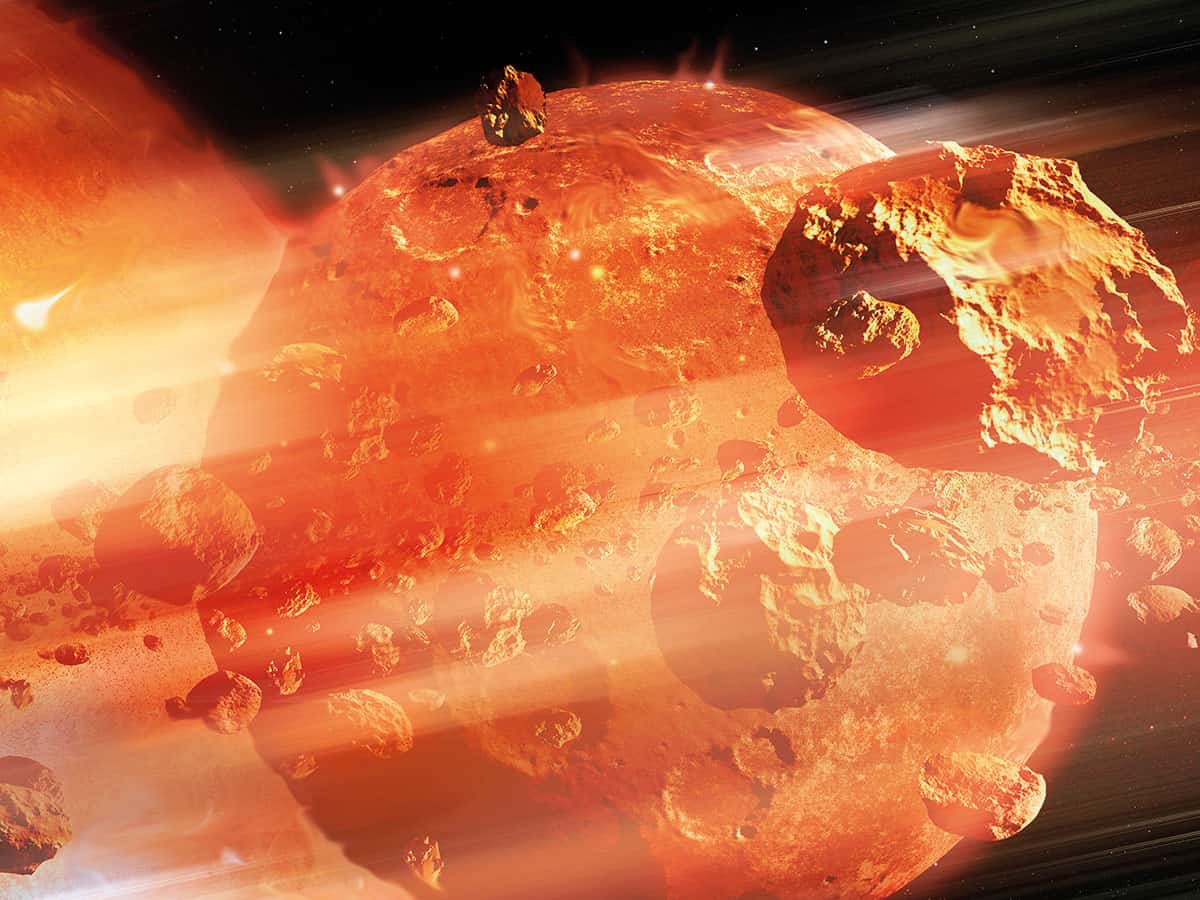

Some planets may have formed with moons right from the outset, like Jupiter’s largest satellites. Others wound up capturing smaller bodies that became gravitationally drawn to their vicinity, like Neptune’s Triton or Saturn’s Phoebe. But these are the gentler options available for creating moons, and nature is not always gentle. As these massive bodies sped through the solar system during its infancy, they occasionally smashed into one another, colliding with energies far exceeding even the catastrophic impact that wiped out the dinosaurs.

These giant impacts may be rare today, but would have occurred quite frequently during our solar system’s infancy. Back at the beginning, none of the rocky planets would have had moons, as these inner worlds are too small to either form with a moon, or capture one via their gravity. But a large impact on one of these worlds would kick up debris that would coalesce in orbit around the planet, capable of forming one or more satellites. When scientists first brought up this possibility as the origin of Earth’s large moon, few took the idea seriously.

One step from Earth

But then something happened: between 1969 and 1972, we actually went to the Moon six times, and returned samples from it. Surprisingly, we found that the Moon had the same stable isotope-ratios that the Earth does, indicating a common origin. The properties of the Moon’s core match those of the Earth’s interior, and the Moon’s orbit around the Earth is oriented with – rather than against – our planet’s rotational axis. Modern simulations of collisions can reproduce not only our own Earth–Moon system, but the satellites of other small worlds, such as the two moons of Mars (there may have been a larger, third moon that fell back onto the red planet) or the five satellites of Pluto. After countless generations of wondering how and when our Moon was created, science has given the answer: a fast, energetic collision, some 4.5 billion years ago.

Missing moon

It was likely mere cosmic coincidence for the young Earth to experience such an impact, and a completely random outcome of it left us with such a large, natural satellite. In fact, relative to the size of the Earth, our Moon is more massive than any other planet–moon combination in the solar system. Indeed, it’s enough to make one wonder what would be different on our world if we didn’t have our Moon.

Although it shines only because of reflected sunlight, the Moon is by far the brightest object in Earth’s night sky. In its full phase, the Moon is 14,000 times brighter than Venus, the second-brightest object in our sky. From an ideal dark-sky site, the human eye is capable of viewing up to 6000 stars at once; along with the Milky Way, a handful of distant galaxies, and even zodiacal light – the diffuse glow of sunlight scattered by interplanetary dust. A full Moon can wipe practically all of that away, eliminating everything except perhaps the brightest 10% of stars from humanity’s view. Without a Moon, we would be rid of one of the biggest natural impediments to pristine, dark skies every night of the year from every location on Earth.

But we would also lose the stellar show that is an eclipse – indeed, we would no longer have eclipses of any type. Solar eclipses require the Moon to pass between the Earth and Sun, blocking out part (during a partial or annular eclipse) or all (during a total eclipse) of the Sun’s light from a particular set of locations on Earth, and they’re one of the most spectacular natural phenomena to occur on our world. Lunar eclipses occur when the Moon passes into the shadow created by the Sun shining on the Earth. Without our Moon in the sky, none of these celestial events would occur for us.

Time and tide

Another consequence of not having the Moon would be that the duration of a day wouldn’t change over time. It’s hard to believe, but our planet’s rate of rotation has slowed down tremendously over its history. Back when dinosaurs roamed the Earth millions of years ago, a single day took only 22 hours, rather than the modern 24. Billions of years ago, when single-celled organisms were the only life-forms around, our planet completed a full 360° rotation in under 10 hours. And our calendar, so well-calibrated today, will require further changes as time goes on. In another 4 million years, Earth’s rotation will slow significantly enough that we’ll no longer need leap days. The reason for this is that the Moon exerts a frictional force on the spinning Earth, causing its rotation to slow over time, and causing the Moon itself to slowly spiral away. If our Moon suddenly disappeared, Earth’s rotation rate would never change over time; it would be 24 hours per day from now until the Sun itself runs out of fuel.

To the Moon and back

Our tides would also be tiny compared to the ones we experience today. If you live near the oceanic coast – particularly by a bay, sound or inlet – you’ll notice enormous differences between high and low tide. The primary cause of the oceans bulging, and the rotation of the Earth causing two high tides and two low tides per day, is the gravitational effect of the Moon. The Sun also pulls on the oceans, but with only one-third of the effect of the Moon. During full and new moons, where the Sun, Earth and Moon are aligned, we get the highest high tides and the lowest low tides: spring tides. When the Sun, Earth and Moon form right angles, during a half-moon phase, we have neap tides, which have only half the tidal differences of spring tides. Without our Moon altogether, the tides would always be a constant, paltry size: a quarter the magnitude of spring tides and half the magnitude of today’s neap tides.

Most disturbingly of all, our Earth’s axial tilt would be unstable without our Moon. Earth currently spins on its axis with a 23.4° inclination to the plane in which we revolve around our Sun. Over tens of thousands of years, this tilt changes: from as little as 22.1° to as much as 24.5°. This relative stability is largely due to our Moon, which carries so much angular momentum that it prevents our rotational axis from changing by very much. Planets like Mars, which rotate with nearly the same period as Earth, but have no large moon to stabilize their rotation, see their axial tilts change by 10 times the amount that Earth’s does. If we didn’t have a Moon, our tilt could exceed 45° at times, making us more like Uranus: a world that rotates on its sides. The poles wouldn’t always be cold; the equator might not always be warm; ice ages would migrate across the globe every few thousand years. Without a Moon, a long-term stable climate might not be possible at all on our world.

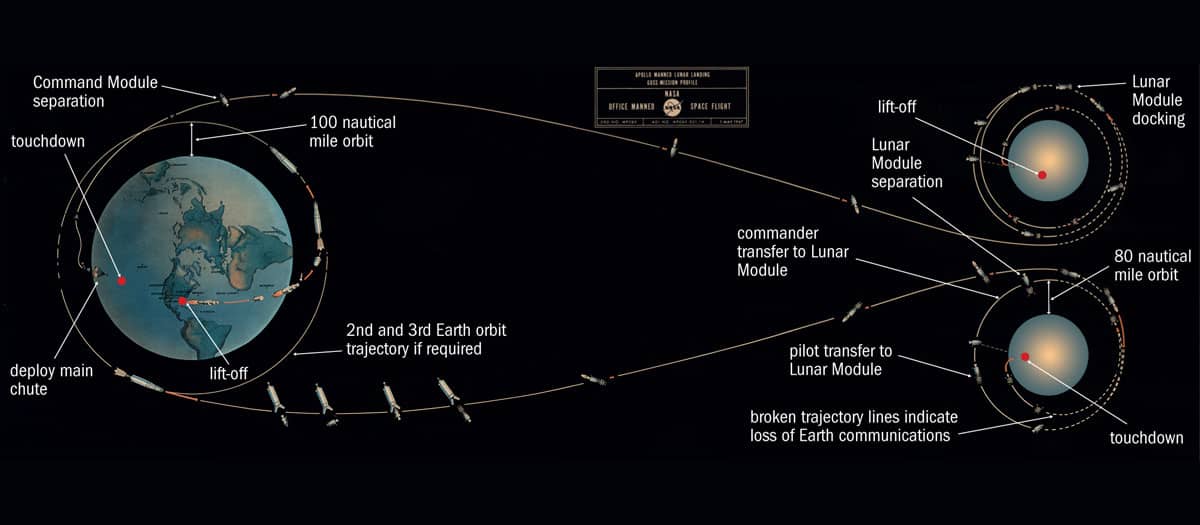

A greater leap

Finally, space exploration would have a much, much more difficult time reaching a world beyond our own. As soon as we developed the rocketry capabilities for crewed spaceflight to escape from Earth’s gravitational pull, we set our sights on our nearest neighbour. The Moon has a slew of advantages over any other potential target for a human landing on it. It has no atmosphere, meaning that there are no winds to contend with upon take-off or landing. It rotates slowly, so any mission under 14 days in duration could spend the entire time in sunlight. And most importantly, it’s close to Earth. A conventional, chemical fuel-driven rocket can make the journey in just three days; a communications signal at the speed of light can make the round-trip journey in 2.5 seconds. The Moon is a mere 385,000 km away, on average; whereas the next-closest planets, Venus and Mars, are approximately 100 times more distant, even during optimal alignments. Our Moon is a natural stepping-stone to the solar system, and the universe. Without it, our first small step on another world would have required a far greater leap for humankind.

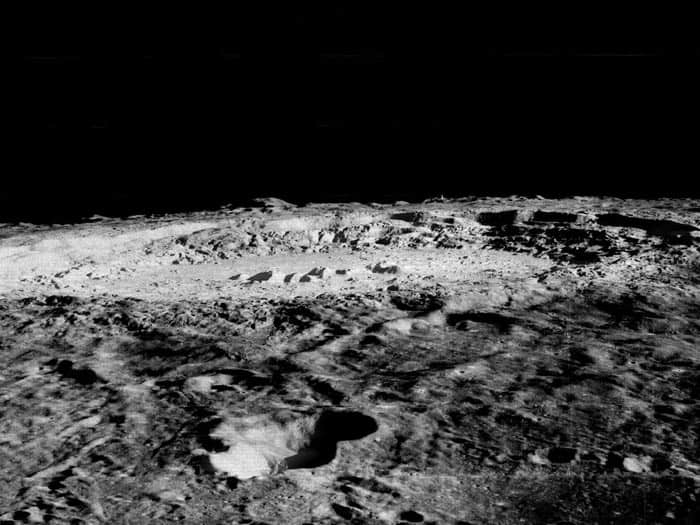

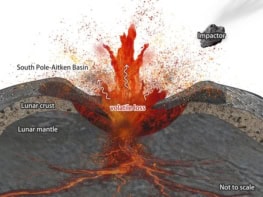

Simulating lunar craters and the impacts that cause them

There are still so many open questions we have about our Moon, and about moons in general. What was the collision that created our Moon like? How large was the object, where did it originate, and how quickly did it strike our world? Simulating the possibilities has led us away from the “giant impact hypothesis” – the idea that an ancient co-orbiting world dubbed Theia collided with our planet – and towards a new structure known as a synestia: a hypothesized torus of debris that coalesces into one or more objects. Ongoing and future studies of the lunar surface composition and its interior properties may yet reveal further information about the formation of the Moon, shedding light on what occurred during our solar system’s earliest times.

Many moons

There was no guarantee for our planetary history to have unfolded as it did. Collisions between massive bodies are rare, infrequent, and random. If we were to create practically identical conditions to the ones that existed in our early solar system, yielding an Earth–Moon system is just one of many possibilities. We could have had no moons at all, similar to Venus or Mercury. We could have formed a moon close by, which would have broken up and fallen back to Earth; perhaps we’d have developed a giant ridge along our equator, similar to Saturn’s Iapetus, or an enormous oceanic basin, like we find on Mars. We could have even wound up with many other combinations of naturally sized satellites, such as a single large moon along with many smaller moons, like those possessed by modern-day Pluto.

Multiple moons would give rise to a number of fascinating consequences on Earth. Finding true darkness could become an enormous challenge, as light from the reflected sunlight off of an array of moons might illuminate the night in an inescapable fashion. Periodic lunar alignments could create catastrophically large tides on occasion, making certain locations on Earth either challenging for human habitability, or a true surfer’s paradise. Even phenomena reserved for the satellites of the gas giants – like moons eclipsing other moons or causing double or even triple eclipses on the planetary surface – could have been commonplace here at home. We’d even have multiple nearby worlds to study, explore and provide additional clues concerning the origin and formation of planetary systems.

In reality, we have only one natural satellite to keep the Earth company as we journey around our Sun, and it’s been with us for the latter 99% of the solar system’s history. Our world, and the life that inhabits it, is forever changed by the presence of our nearest neighbour. As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of humanity’s first touchdown onto the lunar surface, we also celebrate the knowledge of all the ways our Moon continues to influence our planet. Without it, our skies, orbit, oceans, space programme and more just wouldn’t be the same.