When astronomers train their telescopes on the heavens, they are not always looking for the most distant objects in the sky. Indeed there is much to be learnt from focusing a telescope closer to home. The amount of variety in the solar system alone is staggering, although recent observations of planets around other stars suggest that the pattern of planets orbiting the Sun is the exception rather than the rule. Little wonder that a convincing explanation of the origins of the solar system still escapes us.

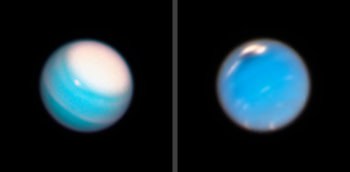

Prompted by 21 July being the 30th anniversary of Neil Armstrong’s “one small step for man”, and by the total solar eclipse that is due on 11 August, this issue of Physics World highlights just a few areas of current research into the solar system. There may not be life on Mars but magnetic measurements strongly suggest that the surface of the red planet has been shaped by plate tectonics. There is water on the Moon for certain, but there is much about our nearest neighbour that we do not know, for instance its detailed composition and volcanic history. We will not see much of the Sun during next month’s solar eclipse, but solar physicists will be scrutinising those regions that are visible as part of the on-going quest to improve our knowledge of our nearest star. One burning question is how does the Sun’s corona reach temperatures of 2 million kelvin? And in the far reaches of the solar system, beyond the orbit of Neptune, lies an intriguing collection of objects called the Kuiper Belt. Although the first Kuiper Belt object was only spotted in 1992, there is already evidence for water-ice on at least one of these bodies.

Space has also been presented as “an essential laboratory in our journey beyond the Standard Model [of particle physics]” by Dan Goldin, head of the US space agency NASA, in a recent keynote speech. Goldin told a group of particle physicists and cosmologists that NASA is willing to help them test theories that unify the fundamental forces of nature at energies many orders of magnitude beyond those available at accelerator laboratories. Although particle physicists did not appreciate Goldin’s references to accelerators built with “yesterday’s technology”, they can afford to ignore them given NASA’s minimal role in funding high-energy physics at present.

Astronomers, on the other hand, would be advised to pay attention to comments made by Goldin in a speech to the American Astronomical Society a few days later. Goldin focused on astrobiology and the search for the origins of life as one of NASA’s top priorities. This will require a vast amount of new technology in optics, materials, propulsion, robots and many other areas. Astronomers need to pay particular attention to Goldin’s comment that “too many of you are hugging the Hubble Space Telescope” and to the six new principles outlined in his speech. The fifth principle, for instance, calls for an astronomical equivalent of “Moore’s law” that would involve the collecting area of telescopes doubling every ten years or less, rather than every 25 years as currently happens. The sixth is “to let go of old observatories when new technologies are ready for launch”.

Rising to the many multidisciplinary challenges that exist in space will keep astronomers and others busy for decades to come.

Tell us what you think

Magazine editors, like physicists, have to rely on intuition and experience for much of the time. There is, however, no substitute for hard data, which is why this issue of Physics World contains a reader survey. Please take the time to complete the questionnaire and let us know what you think of the magazine. Are the articles too difficult? Do you want more book reviews? Is the balance of coverage across the different areas of physics right? The survey can also completed via the Web. We look forward to your answers.