The words "cold fusion" immediately sprang to mind when it was announced last month that a team of researchers led by Rusi Taleyarkhan of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee was due to publish a paper with the title "Evidence for nuclear emissions during acoustic cavitation" in the journal Science.

Taleyarkhan and co-workers had not found a way to initiate fusion reactions at room temperature – in other words there was nothing cold about their experiment. Rather, they had found a relatively simple way of achieving the extreme temperatures needed for fusion in a table-top experiment. However, like the case of the two electrochemists who claimed in 1989 to have demonstrated fusion in an electrolysis cell at room temperature, other experts in the field were not convinced by the number of neutrons produced in the alleged bubble-fusion reactions (see article).

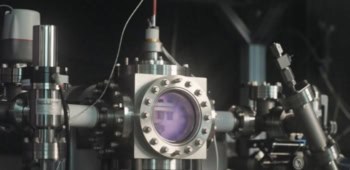

Whereas cold fusion was announced in a blaze of publicity about endless sources of cheap energy and was first published in a journal read by few, if any, fusion scientists, Taleyarkhan and co-workers are to be commended for sending their manuscript to a high-profile journal that rejects many more submissions than it accepts. Their paper reports how they used high-energy neutrons to create tiny bubbles of gas in a beaker of deuterated acetone, and then used an acoustic field to force the bubbles to expand and collapse. They claim that temperatures in excess of 106 K were produced when the bubbles collapsed, leading to the fusion of two deuterium nuclei to produce either a tritium nucleus and a proton, or helium-3 and a neutron. No effect was observed when “ordinary” acetone was used.

The management of the Oak Ridge laboratory is also to be commended for asking two other physicists at the lab – Dan Shapira and Michael Saltmarsh – to repeat the experiment. If Shapira and Saltmarsh had been able to confirm the phenomena, it would have kick-started a wave of activity in an exciting new sub-branch of physics. But when they failed to find enough neutrons or tritium nuclei, questions should have been asked. The paper published in Science was modified in the light of the Shapira and Saltmarsh results, and includes a reference to them (and to a rebuttal by Taleyarkhan et al.). Doubts about the paper increased when it emerged that it had been seen by 13 or 14 referees during the peer-review process.

In an editorial about the paper, Donald Kennedy, the editor-in-chief of Science, defends the decision to publish: “Our mission is to put interesting, potentially important science into public view after ensuring its quality as best as we possibly can. After that, efforts at repetition and reinterpretation can take place in the open. That’s where it belongs, not in an alternative universe in which anonymity prevails, rumor leaks out, and facts stay inside. It goes without saying that we cannot publish papers with a guarantee that every result is right…What we ARE sure of is that publication is the right option, even – and perhaps especially – when there is some controversy.”

While Kennedy makes a strong case for publication, one must wonder why Science declined to peer review the paper by Shapira and Saltmarsh for possible publication in the same issue. Shortage of time is not a convincing reason: the research had already been performed and the results written up; the original paper had been with the journal for about a year, so a few weeks would have made little difference; and electronic publishing allows research papers to appear on line as soon as they have been sub-edited and proof-read, removing the delays associated with print.

The emission of light by bubbles subjected to acoustic waves sounded like science fiction when it was first reported in the early 1990s, but “sonoluminescence” is now universally accepted, if still not fully understood. Bubble fusion may have an equally illustrious future – but the signs are not good.