Should the Nobel Prize for Physics be awarded to more than three people?

The average age of the winners of this year’s Nobel Prize for Physics is 78 – higher than at any time in the past 20 years. That is not the fault of the winners, of course, and the Nobel committee is not entirely to blame either. The neutrino experiments of Ray Davis Jr, who is now sadly in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, and Masatoshi Koshiba involved a lifetime’s work: it is only recently that their true importance – they provided the first evidence that neutrinos can “oscillate” and must therefore have mass – has been confirmed. Riccardo Giacconi, on the other hand, could have been recognized for his contributions to X-ray astronomy a decade ago, but he has had to wait until the floods of data from the Chandra and XMM-Newton observatories made his case irresistible. That said, the decision to award the prize to astrophysics – only the fourth time this has happened – is to be applauded.

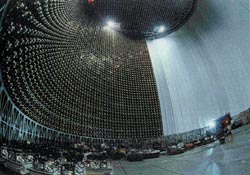

The neutrino experiments recognized by the Nobel committee actually have curious links with particle physics. Koshiba built the Kamiokande experiment in an effort to detect proton decay. Grand unified theories had predicted that this extremely rare process would have a half-life of 1032 years or more. Proton decay has still not been detected, but by lowering the threshold energy of his experiment, Koshiba was able to detect solar neutrinos instead. Meanwhile Davis had to present his experiment to Maurice Goldhaber, his boss at Brookhaven, as an experimental check on a surprising prediction concerning a transition from the ground state of the chlorine-37 nucleus to an excited state in argon-37. Davis’s long-time collaborator John Bahcall described the meeting with Goldhaber as follows: “As Ray had hoped, Maurice was much interested in the nuclear-physics ideas and tests, and, perhaps incidentally, also approved the solar-neutrino experiment.”

Mention of Bahcall raises the question of how many people can share the prize. The Nobel statutes allow a maximum of three people to receive the prize. If Giacconi had been honoured previously, Bahcall would surely have shared the prize with Davis and Koshiba for this theoretical work on solar neutrinos – without his predictions there would not have been a solar-neutrino problem to solve.

Is there a case for awarding the prize to more than three people? The Nobel Peace Prize was shared by Joseph Rotblat and the Pugwash movement in 1995: might a collaboration or laboratory share the physics prize in the future? There is much to be said for not diluting the prize, but it is also true that many great physicists who deserve a prize die without receiving one. At the very least the committee should continue its practice of recent years and recognize the current maximum of three physicists every year.

Physics World and Jan Hendrik Schön

Physics World does not publish original research findings. However, we do publish articles about research papers that have been published in peer-reviewed research journals. We are therefore alerting readers to three Physics World articles about papers by Jan Hendrik Schön, the physicist who has been fired by Bell Labs following an investigation into scientific misconduct.

“The fractional quantum Hall effect goes organic” (Physics World October 2000 pp26–27) was based on J H Schön et al. 2000 Science 288 2338. This paper has now been retracted.

“Organic research goes into overdrive” (January 2001 p9) discussed results from a series of papers that Schön et al. published in 2000. These papers have now been retracted.

“Pumped up buckyballs” (October 2001 p3) was based on J H Schön et al. 2001 Science 293 2432. This paper has now been retracted.

For more information see Bell Labs physicist fired for misconduct and In the matter of J Hendrik Schön.