Particle physicists in the US are excited about their involvement in the Large Hadron Collider, but Nigel Lockyer says they must ensure their future after 2010 once all the major US high-energy-physics accelerator programmes have ended

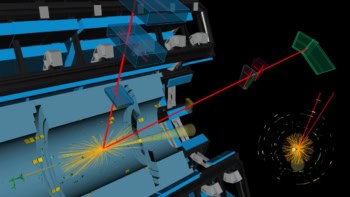

US particle physicists, along with their funding agencies, are anxiously anticipating what is in store for the 14 TeV Large Hadron Collider (LHC). Discovery expectations are extremely high – in particular the prospect of finding the Higgs boson or evidence for supersymmetry. The LHC was an opportunity that opened up in Europe after a similar US programme – centred on the 40 TeV Superconducting Super Collider (SSC) – was cancelled by the US Congress in 1993 after about $2bn had already been spent building the $8.25bn machine. That decision, while devastating, was mitigated by the ability of US physicists to go to CERN, help build the LHC and harvest the physics discoveries.

Additional mitigating factors were the discovery of the top quark – the sixth and final quark of the Standard Model – at Fermilab’s Tevatron collider in 1995 by the CDF and D0 experiments, and the co-discovery by researchers at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) and at KEK in Japan of CP violation in the bottom-quark system. Indeed, until the LHC switches on late next year, Tevatron remains the highest energy accelerator in the world, colliding protons and antiprotons at energies of about 2 TeV.

Physicists at Fermilab are highly focused on finding evidence for the Higgs particle or even supersymmetry, both of which have a small chance of being found at the Tevatron in the next two or three years. Indeed, European colleagues tell me they are quite nervous about being scooped. Of course, once the LHC experiments present their first physics results, the Tevatron will probably be turned off, although no precise date has been set yet.

Joining forces

The formal move to join the LHC began in 1994 when a committee of the US High Energy Physics Advisory Panel, chaired by SLAC’s Sidney Drell, released a report on the future of US particle physics. Based on its recommendation, the US government promised over $500m to the LHC accelerator and detectors, and has fully delivered on its financial commitments. Today, more than a fifth of the members of the ATLAS and CMS collaborations – the LHC’s two main experiments – come from the US, forming a significant fraction of the entire US high-energy-physics community.

CERN is also reaching out to the world for help in developing the LHC and performing research for future upgrades. The US has responded by creating the LHC Accelerator Research Program (LARP) and by sending accelerator physicists to CERN, many of whom have valuable experience with superconducting colliders, such as the Tevatron and Brookhaven’s Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider. LARP is essential for attracting and training young US physicists at a frontier accelerator. A fellowship programme has also been set up to allow young US accelerator physicists to be trained at the LHC.

LHC is reciprocity: many young European particle physicists were trained at US facilities, while the LHC was being planned and built. Indeed, about half of the people working on CDF and D0 at Fermilab, as well as on the BaBar experiment at SLAC, are from outside the US, mainly from Europe. Particle physics will rely on this cost- and resource-sharing model even more in the future.

Tricky times

The US is, however, facing a critical phase over the next two or three years. The Tevatron will be turned off, Stanford’s linear accelerator is transforming into a major light-source facility, while Cornell’s Electron Storage Ring is winding down. As my European colleagues often remark, a lack of investment in particle physics by the world’s largest economy would send ominous signals to science-policy leaders in Europe and Asia that particle physics is no longer an essential science.

Fortunately, the recent EPP2010 report released by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) has given a significant boost to particle physics in the US. It was drawn up by a diverse committee, about half of whom were non-particle physicists, chaired by eminent Princeton University economist Harold Shapiro. “Leadership in science remains central to the economic and cultural vitality of the US,” the report says, adding that the US would pay too high a price if it forfeited its leadership in particle physics.

That theme was echoed in the widely acclaimed NAS report “Rising above the gathering storm”, which has been a major impetus for President Bush’s American Competitive Initiative (ACI). The ACI aims to double the budget of the Department of Energy’s Office of Science and the National Science Foundation, which includes high-energy physics. Although high-energy physics is not an explicit part of the ACI, it has benefited from the initiative, the first instalment of which was in the president’s 2007 budget request to Congress. However, the US particle-physics budget would need to double over the next 7–10 years if the US is to host a major facility such as the International Linear Collider (ILC).

Unlike the SSC, the ILC is a truly international project. The US particle-physics community is strongly aligned behind this global approach and is working closely with Asia and Europe to bring the ILC to fruition. As the EPP2010 report rightly points out, significant investment in accelerator research will be needed over the next few years to optimize its design.

The LHC was conceived at CERN, and it was CERN that decided to move forward with the project. The ILC, in contrast, is an opportunity for the global community to support the next major project no matter where it is located. This model of global co-operation is critical if we are to answer the compelling scientific questions sure to be raised by the discoveries at the LHC.