The European Spallation Source is firmly back on the agenda with several countries unveiling bids to host the world-beating neutron facility. Edwin Cartlidge reports on the lab’s dramatic change in fortune

When the German government announced in February 2003 that it was withdrawing its support for the European Spallation Source (ESS), the news came as a serious blow to neutron scatterers across the continent. First proposed in 1991, the ESS was to be the world’s most powerful source of neutrons and was designed to ensure that Europe retains its lead over the US and Japan in this valuable approach to materials analysis. Germany’s decision to fund four other large research facilities instead of the ESS precipitated the withdrawal of support from other nations, and the €1.5bn project looked set to be delayed indefinitely or even abandoned altogether.

But times have changed. Continuous lobbying of policy-makers by neutron scatterers across the continent, combined with two very favourable reviews on the scientific importance of a next-generation neutron source – one in the UK and one at a European level – have resuscitated the ESS. In October last year the Spanish and Basque governments declared that they wanted to build the facility in Bilbao, and are currently pledging €300m towards the estimated €1.2bn construction costs. Then in March this year, the Swedish government said that it would provide €325m of the capital costs and 10% of running costs if the facility were built in the university town of Lund in the south-west of the country. And a month later Hungary also officially threw its hat into the ring, although its government has not yet said how much it is prepared to contribute. The UK may also bid to host the facility, although it appears that the British government does not want to back the one group – based in Yorkshire – that has so far put together a proposal.

Peter Tindemans, chairman of the European Spallation Source Initiative (ESSI), which represents neutron labs and their users as well as the various consortia bidding to host the facility, says that with the three firm bids on the table he is very confident that the ESS will now be built. Indeed, he expects that a decision on where it will be built could be taken before the end of the year and that approval of funds could then be forthcoming before the end of 2008. “What is particularly encouraging”, he adds, “is that the governments that have put forward bids are saying they would still participate even if the ESS were not built in their countries.”

The virtue of neutrons

Neutron scattering is widely used by materials scientists, condensed-matter physicists, chemists and biologists to probe the structure and physical properties of a wide range of solids, liquids and gases. The technique is similar to X-ray diffraction except that neutrons interact with atomic nuclei whereas X-rays scatter off electrons in an atom. Neutron scattering is therefore very good at pinpointing the positions of light atoms such as hydrogen, which are abundant within biological molecules, for example. Such atoms are hard to locate with X-rays because the intensity of the scattered beam is proportional to the number of electrons in the atom.

Europe’s 4500 neutron scatterers are fortunate in having access to the world’s two most powerful sources of neutrons, the reactor at the Institut Laue-Langevin (ILL) in Grenoble, France, and the ISIS spallation source at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in Oxfordshire, UK. However, these facilities will be overtaken in the near future by the Spallation Neutron Source (SNS) in Tennessee in the US, which will reach a maximum power of 1.4 MW, and a 1 MW source at the J-PARC laboratory in Tokai, Japan.

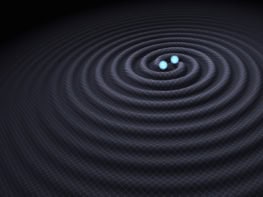

Like the SNS and the J-PARC facility, the ESS was one of a number of new regional sources that a 1998 report commissioned by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development said was needed to make up for an impending worldwide shortfall in neutrons. In common with its US and Japanese counterparts, the ESS would generate neutrons through the process of “spallation”, in which protons are accelerated and then smashed into a mercury target, driving neutrons from the mercury nuclei. At 5 MW it would be considerably more powerful than the US and Japanese machines, providing intense beams of low-energy neutrons. These would be ideal for developing, for example, read heads for computer disk drives, technologies for storing hydrogen, or medical implants.

Despite the ESS promising so much, it was put in limbo by the German government’s decision in 2003 to instead support the construction of a free-electron laser – now known as XFEL – at the DESY lab in Hamburg and an upgrade to the heavy-ion GSI lab near Frankfurt. The UK and French governments also withdrew their support at about the same time. But neutron scientists regrouped, dusted off their plans and launched ESSI in 2004. Their prospects improved in April 2006 when the Council for the Central Laboratory of the Research Councils, which runs the ISIS facility, completed a review of neutron provision with the conclusion that UK scientists would need access to a next-generation neutron source within the next 15 years. Then in October last year, the European Strategy Forum on Research Infrastructures, a body set up by European Union member states and the European Commission in 2002, ranked the ESS among the most mature projects within a list of 35 large-scale facilities that could be built in the continent over the coming years (Physics World November 2006 p8; print version only).

Bob Cywinski, a neutron scatterer at Leeds University in the UK, believes that this endorsement of the ESS, coupled with likely funding for preparatory R&D from the EU’s Seventh Framework programme, means that there is a “very good chance” that the ESS will be built. As Cywinski points out, the design of the facility has been slimmed down by the ESSI – from its original two target stations to one, and there has been a corresponding shaving of the construction costs from €1.5bn to €1bn (in 2000 prices). The single target station – which will serve up to 40 instruments – will be used to produce long (millisecond) pulses of neutrons. These pulses have long wavelengths and can be used to study large structures such as polymers and biomolecules. A short-pulse target station could then be added at a later date. “This approach makes considerable sense,” says Cywinski. “A long-pulse target is entirely complementary to existing facilities and to those being built in Japan and the US.”

Rival bids

Each of the countries putting forward bids believes it can claim the prize. Colin Carlile, a UK physicist who was recruited by Lund University from the ILL, has been impressed by the “open commitment from the university, the region, the national government and industry to build the ESS here”.

Juan Urrutia, president of the executive committee of the Spanish consortium, says that he has no doubt that “Bilbao will be the European city for neutrons.” Meanwhile Laszlo Rosta, scientific director of the company organizing the Hungarian bid, believes that his country may have the edge if European politicians are keen to build an important scientific facility in eastern Europe. He says that the Hungarian government intends to choose between several possible sites (two of which are in or near Budapest) before the end of the summer.

The UK government, however, is proving more reticent. Cywinski, who is heading a consortium of Yorkshire universities that wants to build the facility near the town of Selby, says that the government seems unwilling to discuss the bid even though the consortium has obtained preliminary planning permission. Indeed, a spokesperson for the Department of Trade and Industry told Physics World that “the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory’s expertise in the field of neutrons would make it a highly credible candidate for the next-generation neutron source”, reiterating the government’s previously stated intention to build the ESS at either the Rutherford lab or the Daresbury lab in Cheshire. Member of Parliament for Selby John Grogan points out that with Gordon Brown replacing Tony Blair as Prime Minister, it might be worth “having another go” at putting the Yorkshire consortium’s case to the government.

Negotiating which country should get to build the ESS will almost certainly involve horse trading and political manoeuvring. Tindemans, for example, believes that it would make sense to combine the decision on the site of the ESS with funding arrangements for the XFEL, which is a similar-sized facility that will provide complementary measurements.

According to Tindemans, the host will probably pay between 30% and 50% of the construction costs, with the remainder of the bill likely to be divided out among the other participating nations in proportion to their gross domestic product. In addition to Spain, Sweden, Hungary, the UK and Germany (which had put forward a bid but withdrew it at the end of last year), there are also institutions from France, Switzerland, Italy and Latvia taking part in the project. The total cost of the project over its 40-year lifetime will be about €5bn.

If all goes to plan, construction could begin in 2009, with the first neutrons generated in 2017 and the earliest experiments carried out a year or two later. This would mark the successful conclusion of a long and winding road. For Carlile, however, the fact that two previous designs for the ESS have not been funded makes it imperative that negotiations over the next 18 months go smoothly. “We’ve been to the well twice and returned with an empty bucket,” he says. “If it were to happen for a third time that would be it.”