In order to limit global warming by reducing carbon emissions, Lord Browne argues that the biggest barriers to a low-carbon economy in the UK are not scientific or technological but political

When it comes to climate change, the gap between the vision of both scientists and engineers and the will of politicians is sometimes very stark. The problems caused by the changing climate are now better understood than ever, yet there is a frustrating sense of inertia when it comes to taking action.

The Fourth Assessment Report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) suggests that we must halve global greenhouse-gas emissions by 2050 in order to stand a good chance of limiting global warming from pre-industrial times to 2 °C. The UK’s independent Committee on Climate Change has recommended an 80% domestic reduction in the same period – a target now enshrined in the pioneering Climate Change Act passed in 2008.

Meeting these challenging targets will require nothing less than a revolution in the three areas of the UK’s energy mix: electricity, transport and heating. There are no silver bullets when it comes to low-carbon energy and governments should refrain from picking winners at this stage.

Energy barriers

So what might the future energy mix look like? In power generation, the UK could deploy a whole suite of renewable technologies currently at different stages of development: from mature technologies such as onshore wind plants and biomass energy plants to emerging technologies such as offshore wind facilities and photovoltaic solar cells to experimental technologies in wave and tidal power.

Integrating large amounts of renewable energy while also keeping costs down will require the development of a more flexible, “smarter” grid network that is able to intelligently manage consumer demand by communicating with meters installed in our homes. Energy from nuclear plants and fossil-fuel plants fitted with carbon capture and storage facilities could then provide clean, low-cost base-load generation from secure sources of nuclear fuel and indigenous coal.

In transport – which is currently 95% reliant on oil – first-generation biofuels from food crops are already in use, while second-generation “ligno-cellulosic” biofuels from energy crops are nearing the commercial development stage. Even in aviation, a sector that attracts its fair share of criticism, tests have shown that biofuels can be blended with kerosene in jet-engine fuel. There is also growing momentum behind electric cars, run on either renewable electricity or hydrogen fuel cells.

In heating, which is often forgotten in debates on energy policy, the UK could learn from other countries’ experiments with combined heat and power co-generation plants and district heating networks – using waste heat from small- and mid-scale power plants productively, close to where it is generated. Ground-source heat pumps that make use of natural geothermal energy might also prove to be a viable alternative to natural-gas boilers.

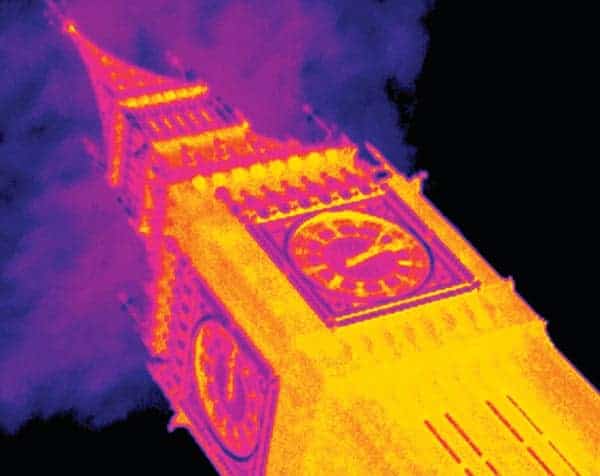

With so many technologies to choose from, it is clear that the greatest barriers to the low-carbon revolution are not scientific or technological. Nor, indeed, are they related to macroeconomic cost – various independent analyses put the figure at just a few percentage points of gross domestic product lost over the coming decades. The biggest barriers are in fact political.

Combating climate change

I would suggest four imperatives for politicians constructing energy policy in response to climate change. The first is not to compartmentalize climate change as an issue. Its effects will be extensive – affecting everything from weather patterns to defence policy – and our response to it must be equally broad. Politicians must lead from the front, demonstrating to their citizens that environmental integrity is a tangible part of other social priorities such as economic prosperity and national security.

Of course, there will be trade-offs between climate change and other social priorities. A potent example is the question of whether to build new coal-fired power plants, which would enhance energy security but at the expense of “locking in” harmful emissions for decades to come. We should not be uncharitable – decisions such as these represent a political dilemma of the highest order and there are few easy answers.

For this reason, the second imperative is to pursue action in areas of activity in which economic prosperity, national security and environmental integrity come together. Using public money for green-energy infrastructure and for energy-efficiency improvements would not only help reduce greenhouse-gas emissions, but also guide the path towards economic recovery and energy security.

There are some who argue that it is not the role of government to stimulate investment in new energy industries. But governments have been doing this for decades and with great success. The UK offshore oil and gas industry was created from virtually nothing during the 1970s and 1980s due, in part, to generous tax incentives and government help to build strategic infrastructure. There is an even greater cause for government intervention today because climate-change mitigation is a public good that would not otherwise be recognised by the free market.

Given this need for greater government intervention, the third imperative is for politicians to rethink the state’s role in energy markets. The market is the most effective delivery system available to society, but it needs strategic direction and a framework of rules if it is to provide the more diversified energy infrastructure that we urgently need.

And in troubled economic times, it is important that the government has a hand in directing financial resources to projects where they are urgently needed. In April the UK’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, Alistair Darling, announced £525m of support for offshore wind facilities that has been immediately successful in unlocking projects worth a combined 3000 MW.

The fourth, and final, imperative is that politicians must seek a global solution to climate change. The immediate battle against climate change will be mostly waged in the developing world. In the next decade, opportunities to reduce emissions in developing countries represent two-thirds of the global potential. What is more, this could be achieved at half the cost of action in the developed world.

What these four imperatives point to is a new direction for government policy in response to climate change. In previous years energy policy has been judged by two metrics: security and cost. To this we must now add a third: low-carbon generation.

The impact of this will affect every sector of the UK economy – from agriculture to finance, and from software management to civil engineering. It may feel a lot like stepping into the unknown but humanity has thrived in those moments where it has most pushed itself. For this generation, the task remains to bridge the gap between the scientifically possible and the politically feasible.

What the politicians say

- Climate change cannot be tackled by politicians on their own but through politicians and people working together Ed Miliband, Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change

- No other major European country generates less of its electricity from renewables [than the UK], although we have some of the best wind, wave and tidal resources in Europe Greg Clark, Shadow Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change

- Developing our renewables as quickly as possible must be the highest energy priority Simon Hughes, Liberal Democrat Shadow Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change