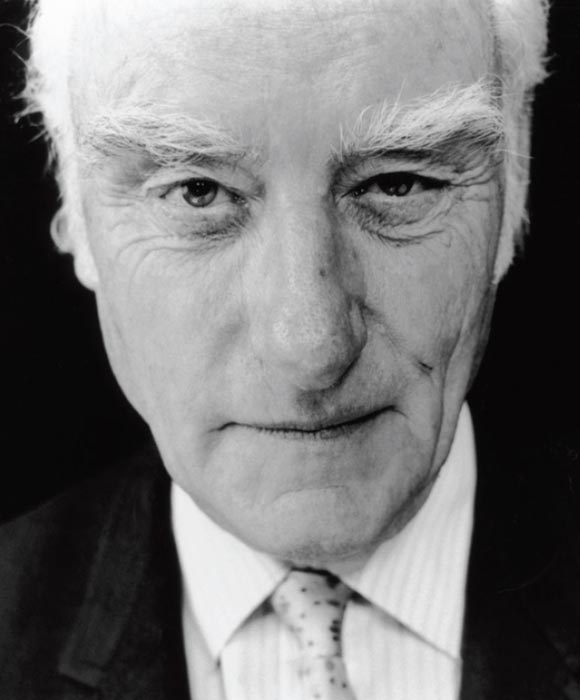

Francis Crick, Hunter of Life's Secrets

Robert Olby

2009 Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press

£30.00/$45.00 hb 450pp

Scientific biographies work best when the biographer manages to place the individual and their science into a broader intellectual context. The reason for this is simple: however worthy and important their achievements may be, few scientists have led lives that are exciting enough in their own right to capture a reader’s imagination for hundreds of pages.

Take Francis Crick. Together with his collaborator, the biologist James Watson, Crick used images produced by X-ray diffraction patterns of biomolecules to work out the structure of DNA, the molecule that carries heritable information of most life on Earth. He is thus without a doubt someone whose scientific achievements have had an impact far beyond his own area of research. However, he is not as personally colourful as some scientists, although his life does offer some interesting material. But the most significant thing for would-be biographers is that he did his most important work during the period immediately following the Second World War – a time of great turmoil, some of which was linked to the science that engaged Crick and his many collaborators.

In Francis Crick: Hunter of Life’s Secrets, University of Pittsburgh historian Robert Olby does a wonderful job of conveying how Crick’s personality and environment shaped his science. Olby traces Crick’s way of doing research – which appears intimately linked to the way he dealt with his contemporaries – in a nuanced and illuminating manner. He refrains from judging his subject, preferring to imply rather than spell out the sharper edges of Crick’s character, and leaves it to the reader to assess Crick as a scientist and person. Olby’s work is not, however, a hagiography, nor a popular biography that you are likely to pick up in an airport bookshop. Instead, he offers a scholarly and well-researched (though highly readable) account of the life, quests and times of one of the most famous scientists of the 20th century.

After studying physics at University College London, Crick was a year or so into a PhD on measuring the viscosity of water at high temperatures when the war began. Abandoning his PhD in favour of the war effort, he went to work designing mines at the Admiralty. According to Olby, a family friend of the Cricks, it was this diversion, plus the attraction of challenging scientific problems with potentially huge paybacks, that drew Crick away from physics to the fledgling discipline of molecular biology.

After embarking on a PhD in this new subject at the University of Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory, Crick honed his analytical skills by determining the structure of several small – but, crucially, helical – proteins. Through a combination of model-building and seemingly endless discussion with Watson and others, he gradually became convinced (somewhat against the Cavendish’s prevailing opinion at the time) that it was DNA and not proteins that carried heritable information. Crick’s expertise was not in experimental crystallography but rather in the building of models, a task that consisted of placing pieces of cardboard or metal on a pipe-and-rod scaffold and calculating the diffraction patterns until he had found a structure that was in agreement with available data. These “modelling” skills and the insights he gained from his conversations proved immensely helpful in deducing the double-helical structure of DNA.

During this period, Crick and the equally driven Watson clearly fed off each other’s ideas. It was this fruitful collaboration that ultimately allowed them to win the race to understand the structure of DNA. The fact that they were able to do so despite formidable opponents (including, among many others, Linus Pauling) also reflects the freedom that they were granted – sometimes grudgingly – by Lawrence Bragg, the Nobel-prize-winning physicist who was director of the Cavendish at the time.

I found the discussion of Crick’s research at the Cavendish the most interesting part of the book. Although this story is well known through previous accounts, including those by Crick and Watson themselves, Olby does a remarkable job of summing up the controversy surrounding Watson and Crick’s decision to use unpublished X-ray diffraction images obtained by Rosalind Franklin and other colleagues. Compared to Watson, Crick perhaps escapes lightly in this account, but the resentment and tension that must have existed between the different players is tangible. The real or perceived slights felt by competing researchers, including Maurice Wilkins who went on to share the 1962 Nobel Prize for Medicine with Crick and Watson, will no doubt continue to attract attention and scrutiny.

Olby shows how in his later career Crick applied the same skills that had enabled him to solve the structure of DNA to a range of other biological problems, including his explanation of the “universal” genetic code, which describes how the 20 amino acids are encoded (or stored) in the DNA sequence: groups of three nucleotides represent an amino acid. This was perhaps his most impressive intellectual feat. Even though the code is not even universally valid for life on Earth (the mitochondrial “power-plants” inside our cells, for example, employ a subtly different code) it continues to intrigue: given that the four nucleotides – A(denine), C(ytosine), G(uanine) and T(hymine) – can be combined to produce 64 possible three-letter codons, it is still unclear why one particular mapping of 64 codons onto 20 amino acids should be used. This remains an active area of research.

One theme that Olby stresses throughout is the importance of younger collaborators for Crick’s way of working. When he was studying the details of the genetic code, Crick surrounded himself with up-and-coming scientists, frequently inviting them to Cambridge to discuss his models and improve them through discussion. These younger scientists, in turn, benefited from his extensive knowledge of the research literature. Many of them ended up with Nobel prizes themselves, including Aaron Klug, Sydney Brenner and, of course, Watson. Clearly, they were more than just sounding boards for Crick’s ideas. Yet relations between Crick and his colleagues (even Watson) were not always cordial. Moreover, while in his work he relished the intellectual challenge posed by younger collaborators, in his extramarital affairs he sought out young women who, by and large, were not in a position to challenge him (or his marriage). Although he maintains a neutral position, Olby skilfully teases out these complex social dynamics.

During the late 1960s, Crick gradually drifted away from molecular biology and moved to the US (the latter apparently for tax reasons). Never one to shy away from big challenges, he eventually decided to tackle the one problem that he considered sufficiently challenging and worthy of his attention: the nature of consciousness. The principle that consciousness must have a biological, biochemical and ultimately physical origin was never in doubt for Crick, who, despite his non-conformist family background, never had much time for religion.

But compared with molecular biology, where experiments to test our ideas are relatively straightforward to conceive and execute, the experimental verification of ideas related to consciousness is an entirely different undertaking. The potential confounding factors are too complex and manifold, while the neurophysiological responses to external stimuli are too variable and subtle. Yet up to his death in 2004 at the age of 88, Crick nevertheless believed that he could make important contributions to the theory of consciousness.

Nobody can doubt the importance of that field, but the lack of hard facts or sufficient amounts of reproducible experimental data – there are no X-ray diffraction patterns here – make it hard to build, calibrate and test models. It is perhaps not surprising, therefore, that Crick did not add much more than ideas to this field. Although he clearly enjoyed this topic, he could not repeat his previous successes, which had been based on his real strengths: formulating, testing and quickly dismissing wrong ideas in the light of data, until he came up with something lasting.