Too Hot to Touch: the Problem of High-Level Nuclear Waste

William and Rosemarie Alley

2013 Cambridge University Press £19.99/$29.99hb 383pp

The second law of thermodynamics is alive and well. Not only does everything we do generate waste – from cooking to working in an office and even just breathing to oxidize whatever food we have eaten – we also have entropy marching on, churning out ever more disorder. Making electricity is no exception. The process of constructing solar panels or wind turbines increases entropy and generates waste; so does the generation of electricity with gas, coal, oil or nuclear power. The creation of waste is inevitable. The question is: what do we do with it?

This question rests particularly heavily on the nuclear industry. Although everything on the planet is radioactive to some degree, history has shown that when the specific activity of a material rises to a sufficiently high level, such as that found in spent nuclear fuel, disposing of this material as waste has proved to be entirely untenable. This is true even though many common household items – bleach, paint and motor oil among them – actually qualify as hazardous waste, and the typical controls required for disposing of them are fairly similar to those required for low-level radioactive waste. If we can cope with these types of waste, we should also manage to handle the radioactive stuff; from a scientific or technical point of view, the issue is not insurmountable.

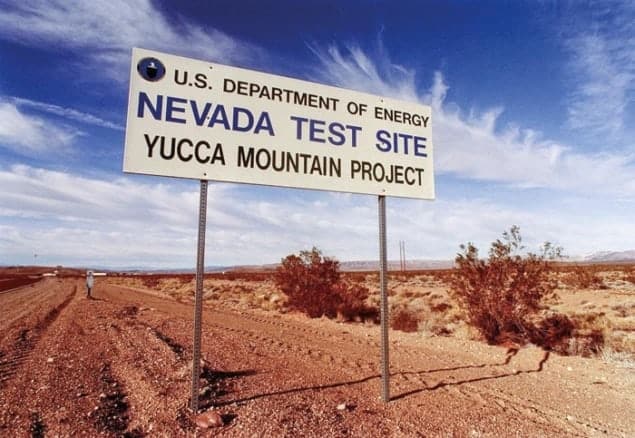

The real problem lies with politics, which in the US and many other countries has continually blocked any long-term solutions involving the permanent disposal of high-level waste. In Too Hot to Touch, William and Rosemarie Alley tackle this problem head on as they review the history of nuclear waste in the US. The book focuses largely on the story of the would-be nuclear repository at Yucca Mountain, Nevada, but it also covers events from the beginning of the nuclear age all the way to 2012. The Alleys form a good team: William is a geologist and former chief of hydrogeology at Yucca Mountain, while his wife Rosemarie is a writer. Throughout, they do a great job of keeping the reader interested in the timeline and historical details. Only a few times do the authors veer off their scientific-review theme to either criticize those who are religious or to make unquantified statements such as their claim that caesium-137 in the body emits “dangerous radiation” (it would have been more helpful to compare it with naturally occurring concentrations of beta-gamma emitters such as potassium-40). Overall, the book is well written, informative and substantive.

Many fun facts are woven into this history. For example, the book describes how the father of the former US vice-president Al Gore, himself a legislator, suggested disposing of nuclear waste along the border between North and South Korea. Al Gore Sr’s idea was to create a no-man’s land that used the “psychological fear” aspect of the waste to prevent troops from crossing. The nation’s history of dumping waste in the oceans and other cases of reckless waste disposal by the US government is also sternly addressed. Overall, the book ascribes substantial incompetence not only to US politicians in general but also more directly and overtly to officials at the US Department of Energy (DOE) and its predecessor organizations ERDA and the Atomic Energy Commission. It even calls out Steven Chu – a Nobel laureate and the most recent past head of the DOE – and President Obama for ignoring the overwhelming amount of science and engineering that went into establishing Yucca Mountain as a viable repository for spent fuel.

The book’s contents are not all bad news for the nuclear industry. The Alleys do bring up one of the chief selling points for nuclear technology, which is that the energy an average citizen of a rich country uses in a lifetime would only generate an amount of spent fuel you could fit into a Coke can. They also acknowledge – and even devote a whole chapter to – the successes of the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) in New Mexico. This DOE facility is a deep geological repository for the permanent isolation of transuranic waste (mainly items contaminated with plutonium) from the biosphere. Unlike Yucca Mountain, it is not only under budget but also ahead of schedule, with a substantially impressive safety and quality record. I am, however, quite biased on this point, being an employee at the WIPP; I and others take great pride in the work we do by safely and permanently removing these hazards from the biosphere. (In addition to my service to WIPP operations and engineering, I also support a dark-matter telescope project housed inside the WIPP repository and am the radiochemistry laboratory director for emergency response applications. There is never a lack of work to do for the WIPP!)

The factors that made the WIPP such a success, whereas Yucca Mountain has still not opened, are discussed in detail in the book but one factor is definitely good geology (with others being public acceptance and political support). The WIPP is situated in the south-western corner of a salt deposit that has a cross-sectional area larger than Florida, and which, at the location of the WIPP, is 600 m thick. Such a configuration makes for a stable, long-term geological repository, allowing it to meet all state and federal regulatory, safety and quality requirements.

The book goes into a great deal of detail over the technical aspects of repository geology, showing how geological knowledge grew and evolved over Yucca Mountain in tandem with the changing politics and regulations, and how these various facets played out in time, bringing us where we are today. I would have liked to have seen it cover more about the remotely handled transuranic waste programme currently under way at the WIPP, along with the progress going on there to make it capable of receiving waste that is “greater than class C” (which means, in simple terms, low-level waste that requires disposal in a geological repository rather than shallow land burial). Still, the real focus of the nuclear industry today is on high-level waste and spent fuel, so it perhaps makes sense that this is where the book keeps the reader focused, too. Overall, this is an excellent book and a nice technical review for anyone wanting to comprehend why the task of dealing with this trash has been so mired in obstacles throughout its history.