What does it take to lead a lab with more than 2000 staff members and an annual budget in excess of €800m? As CERN celebrates its 60th anniversary this month, Sharon Ann Holgate finds out what’s expected of the lab’s next director-general.

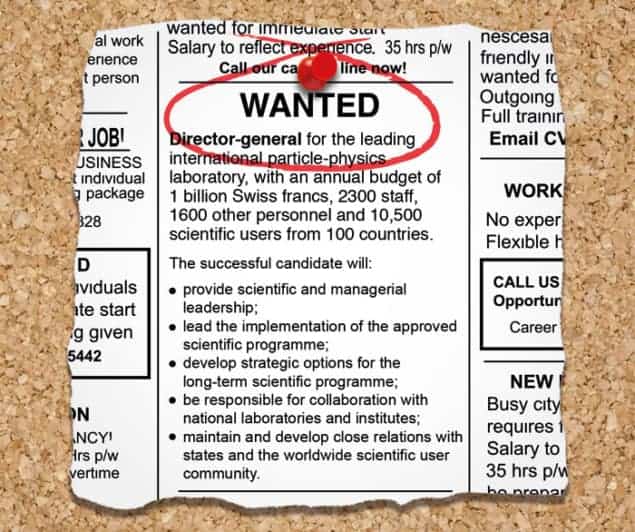

The advertisement on CERN’s jobs site was just over one page long, and its tone seemed almost deliberately matter of fact. “The term of office of the present director-general, Professor Rolf-Dieter Heuer, ends on 31 December 2015,” it stated. “The council is therefore inviting applications.” According to the bullet points that followed, duties associated with being CERN’s boss include leading the European particle-physics laboratory’s research programme (“with emphasis on the full exploitation of the scientific potential of the LHC”) and developing “strategic options” for its future.

For most physicists, the idea of applying for the job of CERN director-general (DG) is only a daydream. Even so, the advert raises some interesting questions. How does someone develop the skills required to lead a lab with multiple scientific experiments, some of the world’s most advanced machinery and 10,500 scientific users from all over the world? And beyond the advert’s broad statements about “effective building of consensus” and “excellent communication and negotiation skills,” what qualities does a CERN boss really need to succeed?

Ask the experts

As one of only 14 people who have served as CERN’s DG since the lab was founded in 1954, Chris Llewellyn Smith knows more than most about what the job takes. Between 1994 and 1998, he oversaw the approval of both the LHC and the final upgrade for its predecessor, the Large Electron–Positron (LEP) collider. According to Llewellyn Smith, leadership, charisma and presentation skills are all necessary, but he also emphasizes the importance of being “a good judge of people” who can choose a capable senior management team and then delegate responsibilities to them. “Any serious candidate to be DG will worry about the expectations and challenges,” he explains. “Having the support of a first-rate team of directors makes it possible to cope with pressures that can be – and in the 1990s were – enormous.” His main challenges, he says, were getting the LHC approved in the face of opposition from some CERN members, and bringing Japan and the US into the project.

One of Llewellyn Smith’s predecessors, Herwig Schopper, emphasizes the motivational aspect of the role. “Formally, the DG of CERN has all the power, and is only controlled by [the lab’s] council,” he explains. “But in practice the spirit and mentality of CERN is completely different. It’s very rare that the DG simply gives orders.” Instead, Schopper, who served as DG between 1981 and 1989, says that its leader “has to convince people to go in the right direction and motivate them to fulfil their tasks”. Such skills were particularly important for Schopper when the LEP was being built because the budget was both fixed and lower than it had been in preceding years.

As the current director of Fermilab, the US’s flagship particle-physics facility, Nigel Lockyer agrees that jobs like his are not about giving orders. Any director of a large physics research facility, he says, needs to listen to other people’s views, follow advice and communicate equally well with scientists and non-scientists. In addition, they need to cope well with multiple challenges while maintaining a positive outlook. On a lighter note, he adds, it helps to be someone who “gets excited about learning new?things”.

As for how to develop these qualities, Schopper suggests that prospective DGs should hone their management skills at smaller laboratories, as he did while managing the DESY accelerator centre in Hamburg, Germany. During his tenure, DESY had around 500 staff and 700 foreign users – smaller than CERN but big enough to provide a good management training ground.

In some circumstances, professional training can also help. Colin Hudson, the director of career development at Cranfield University’s School of Management, says that short courses in specific areas (such as complexity management or multinational influencing) might be useful for prospective DGs. For the most part, though, he believes that people in very senior positions can do just as well by working with an executive coach or with a mentor who has held a senior role in the sector.

Lockyer agrees that mentoring is important, noting that he sought advice from CERN’s current DG, Rolf-Dieter Heuer, when he was starting his role at Fermilab. The pair spoke about various topics, including management structure. “Call up your colleagues around the world and find out how they do business,” Lockyer advises. “See what works and what doesn’t work, and tailor it to yourself.”

Room for an outsider?

Skills such as people management, delegation and communication are not exclusive to science, of course. So could someone who has experience of managing a large organization – but no physics training – succeed as CERN’s DG?

Definitely not, says Dave Wark, a University of Oxford physicist who leads the particle-physics department at the nearby Rutherford Appleton Laboratory and is also a member of CERN’s scientific policy committee. “When you’re doing research that is at the very limits of human knowledge…you simply have to understand what you’re doing or you’ll screw it up,” he explains, adding that many of the DG’s decisions come down to making a judgement between different particle-physics arguments. Schopper, too, feels that a manager without a science background would be “completely lost” when making decisions about where to focus research efforts. “At the present time, theory doesn’t really tell us where to look for gold,” he says.

Even so, Cranfield’s Hudson – an engineer who previously directed UK operations for British Gas – believes it’s possible to overstate the importance of physics expertise to the DG’s job. While he stresses that CERN’s leader must understand the sector, the scientific issues and some of the technology, “it is not vitally important for them to be the most qualified physicist there”. If they are, he says, they will probably struggle to present the research in a way that government ministers and other outside influencers can understand.

What the advert leaves out

A few of the qualities that previous DGs found useful are perhaps more surprising. Physical stamina is one example. Llewellyn Smith notes that he flew to North America three times in his first five weeks as DG, and when the lab’s council met, he often stayed up at night writing memos or revising budget plans. During weeks when the council and committees for scientific policy and finance meet, Schopper adds, “sometimes there is no time for a meal and at other times one has to eat two lunches the same day to satisfy important visitors”. Because the lab is an international facility, Llewellyn Smith says it also helps to speak as many European languages as possible.

A more serious challenge, Schopper says, is that the DG sometimes has to take “difficult, lonely decisions and be criticized for developments beyond their control”. For example, both he and Llewellyn Smith had to deal with budget squeezes and make hard decisions about where to direct limited resources. Under the circumstances, Schopper adds, “leading a normal private family life is difficult”.

But despite the challenges, the two former DGs interviewed for this article are quick to mention the rewards of their former job. “It’s fascinating if you can see something can be done which is unique in the world, and promotes our scientific knowledge,” Schopper says. Meanwhile, Llewellyn Smith recalls an occasion when he spent a full hour meeting with China’s then-president Jiang Zemin. “Not many people spend an hour with somebody responsible for a quarter of the world’s population,” he says. “Things like that happen to you as director-general of CERN and are really unrepeatable experiences.”