Chanda Prescod-Weinstein reviews Black Hole: How an Idea Abandoned by Newtonians, Hated by Einstein, and Gambled on by Hawking Became Loved by Marcia Bartusiak

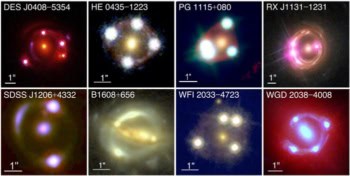

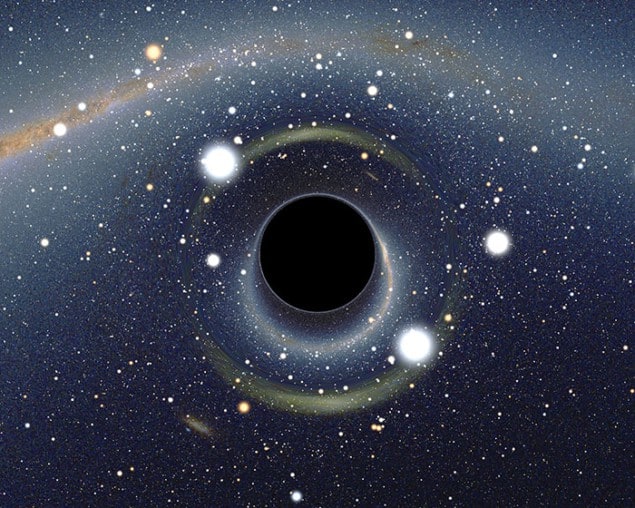

While there have been many popular science books on the historical and scientific legacy of Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity, a gap exists in the literature for a definitive, accessible history of the theory’s most famous offshoot: black holes. When asked for a good introduction to the strange regions of space–time that nothing, not even light, can escape from, one might mention Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time. However, while this text is highly accessible, it primarily focuses on the search for quantum gravity, with black holes playing a smaller role. Meanwhile, Kip Thorne’s Black Holes and Time Warps is all about black holes, but makes a rather demanding read; although it can be compelling for physicists or serious enthusiasts, it is perhaps too long and technical for a mainstream lay audience.

In Black Hole, the science writer Marcia Bartusiak aims for a discursive middle ground, writing solely about black holes at a level suitable for both high-school students and more mature readers while also giving some broader scientific context for black-hole research. Her text works harder than most to straddle the fence between popular-science exposition and history of science. Instead of simply developing the scientific theory and accessorizing it with historical facts, Bartusiak puts forward a thesis about the intimate relationship between the acceptance of general relativity and the acceptance of black holes by the physics mainstream.

One of the pleasures of Bartusiak’s book is her careful word choice and the exquisitely clear explanations of the science involved at every point in the story. Bartusiak holds a faculty appointment in a science writing programme, and this is strongly reflected in Black Hole. Her words are a powerful riposte to the suggestion that writing for a popular audience requires specious oversimplifications of the science at play or repeated use of the same analogies over and over again. Bartusiak invents some novel ways to describe physics, which is a helpful contribution not only for lay readers but also for scientists looking for new ways to communicate their research. I enjoyed her penchant for unusual phrasing – for example, in describing black holes as “wackily weird” in the preface.

Though the first few chapters on the early history of the idea of black holes are somewhat lethargic, the writing bursts into life when she introduces supernovae – stars that have exploded at the end of their lives – to the story. Her account of Fritz Zwicky’s thought process as he developed the first rudimentary understanding of how a supernova might occur provides a useful lesson about how creativity – an often-ignored quality – is required to succeed in science. By connecting ideas from two seemingly disparate areas of physics, Zwicky used imagination rather than algorithm to develop a new and ultimately profound idea.

In some ways, Black Hole succeeds as a history of science book. The main text de-emphasizes dates, improving the book’s accessibility, while Bartusiak has added a helpful timeline at the back for the curious reader. However, her dedication to readability can prove frustrating for readers looking for a more open interpretation of historical events. For example, in describing a famous incident where the British astronomer Arthur Eddington rejected Subramanyan Chandrashekar’s proposed minimum mass for white-dwarf stars, Bartusiak’s account of what happened between Eddington and the Punjabi-born “Chandra” significantly neuters the story in a way that seems designed to make readers comfortable, at the expense of truly capturing what happened. This part of the story is best read in tandem with Arthur I Miller’s book Empire of the Stars, which describes Chandra’s feeling that racism was a factor in Eddington’s behaviour, and also shows the extreme impact that this rejection had on Chandra’s psychological wellbeing for the rest of his life.

Bartusiak does, ultimately, wonder whether things might have been different if Eddington had championed Chandra’s idea instead of eviscerating it. She answers in the form of a quote from the physicist Werner Israel, who says that the culture was simply not ready to accept black holes. But there’s another question that Bartusiak fails to ask, which is this: What compelling discovery might Chandra have made had he not felt so discouraged that he stopped working on black holes for decades? Einstein himself was a staunch anti-racist, so I doubt he would object to us asking this question 100 years after the advent of general relativity, in an era when “diversity” has become a buzzword. Bartusiak misses an opportunity to reflect on the lessons old mistakes ought to teach us about the impact of discrimination on the scientific mission today.

More broadly, Black Hole was, at times, an uncomfortable read for a theoretical cosmologist. One of the book’s central theses is that acceptance of general relativity was predicated entirely on the community’s belief that black holes were a phenomenon worth investigating. In this particular telling of general relativity’s history, the dramatic competition to accurately measure Hubble’s constant (which lasted for more than half a century) never figures into the conversation, even though it happened simultaneously in some of the same research centres as the black-hole story.

Perhaps Bartusiak is correct, and general relativity would have died out as a research area had it not been for the renewed interest generated by black-hole-related discoveries. But Black Hole never makes a truly compelling case for this idea, in part because Bartusiak circumscribes the storytelling to leave out any true mention of cosmology research. Had this been properly accounted for, the thesis that black holes were simply more important to the theory’s long-term viability might be more believable.

Black Hole ends without fully moving into the modern era of black-hole exploration, where intersections with other areas of research, such as cosmology and galaxy formation, are ever-growing. The community has changed, too, with more members of under-represented groups participating in black hole research, although almost none are mentioned in the book. Ultimately, though, Bartusiak’s work fills a much-needed gap in the popular-science literature and provides an excellent introduction for non-experts to the science of black holes, even if it does not completely succeed at capturing the historical arc of black-hole exploration.

- 2015 Yale University Press £14.99/$27.50hb 240pp