Brian Drummond reviews Nagasaki: Life After Nuclear War by Susan Southard

In 1950 US president Harry S Truman was asked about the possible use of an atomic weapon in the Korean War. “It is a terrible weapon, and it should not be used on innocent men, women and children who have nothing whatever to do with this military aggression,” he replied, adding “That happens when it is used.” His reply is instructive, because five years earlier, Truman had authorized the use of such a weapon on the Japanese city of Nagasaki, resulting in the deaths of more than 70,000 civilians and serious long-term illness for an even larger number.

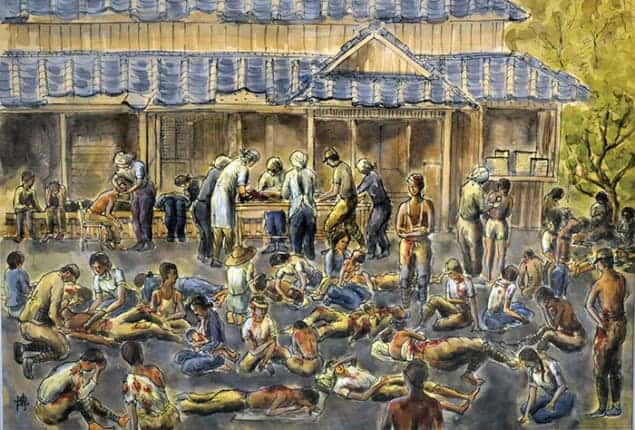

In Nagasaki: Life After Nuclear War, Susan Southard tells the stories of five people who were in the city when it was bombed on 9 August 1945 and who survived into old age. In the days immediately following the bombing, all five of these hibakusha (“atomic bomb affected people”) helplessly witnessed the swift deaths of family members, friends and hundreds of others who had received horrific injuries from the explosion. Most hibakusha received no immediate treatment due to the severe shortage of medics and facilities, and many were confined to bed for months. Later, they endured decades of social stigma as well as a range of physical and psychological illnesses, including multiple cancers, disfigurement and post-traumatic stress. By telling their stories of lifelong suffering, they express hope that there will be “no more hibakusha” in the future.

In relating these personal stories, Southard touches on several aspects of nuclear weapons, including the military, political and historical implications of their use and the scientific study of how radiation affects people. The book’s extensive notes and source listings highlight that these subjects have been covered elsewhere (often by those with more authority on the subject), while a few other relevant topics, such as the physics of nuclear explosions and the status of nuclear weapons in international law, are virtually ignored. However, Southard did interview the hibakusha and others extensively, and within these limits, she clearly illustrates how the various aspects overlap and influence each other. For example, the personal views of the hibakusha that their bodies were “burned from the inside out” overlaps with scientific analyses conducted after the bombing. This research indicates that, in addition to external exposure to radiation, the hibakusha also ingested radioactive materials, which then irradiated their cells internally. Among those who did not survive, autopsies showed severe damage to internal organs, tissue and veins.

By 1950, as the above quotation shows, Truman had made a clear link between the personal impact of nuclear weapons and their military significance. But was such a link made before 1945? The effect of small doses of radiation on human organs, tissues and cells was certainly well-established, and while no studies could be done on people whose entire bodies were suddenly exposed to massive doses of radiation, theoretical analysis would have been possible. Southard suggests that instead of performing such an analysis, US scientists and military leaders made assumptions – for example, presuming that anyone who might be exposed to fatal radiation levels would be killed by the blast. In contrast, other writers (notably Peter Pringle and James Spigelman in their 1983 book The Nuclear Barons) have suggested that (a) scientists knew many would die from delayed radiation effects in subsequent years; (b) they failed to tell the politicians this, not realizing its relevance; and (c) had politicians known that an atomic bombing would result in people dying from radiation effects decades later, they would have regarded it as different from other military options.

Regardless of how much politicians and scientists knew before August 1945, politics certainly influenced science afterwards. As Southard explains, when reports of radiation effects on the hibakusha began to emerge, US authorities dismissed them as propaganda. Indeed, for most of the 1945–1952 US occupation of Japan, censorship effectively blocked all such reporting except for the official US investigations. Research on radiation effects carried out by Japanese scientists during the occupation years was not published until after 1951, and in the US, most media organizations complied with a request that all reporting of radiation effects be approved by the War Department before publication. One extensive US account of the plight of the hibakusha (John Hersey’s Hiroshima) did emerge in 1946, and was widely read; however, an immediate counter-campaign by the US government was so influential that US media reports on the hibakusha virtually ceased. The mushroom cloud became the iconic image of the weapons, with no representation of the people beneath them.

Southard states that she hopes her book will “help shape the course of public discussion and debate over one of the most controversial wartime acts”. As she observes, the view that the use of atomic weapons on Japan “ended the war and saved a million American lives” was promoted by US politicians at the time and “became deeply ingrained as the truth in American perception and memory”. Such views persist to this day, despite the fact that, following the declassification of many relevant documents, “no serious historian regards those as the sole considerations driving the use of the bombs”.

Southard also aims to “transform our generalized perceptions of nuclear war into visceral human experience”. The wording of this aim, and of the book’s subtitle, is ambiguous. A “nuclear war” is generally understood to mean the use of several nuclear weapons by more than one state. According to many recent analyses, the human and environmental consequences of such a war would be so devastating that any “life after nuclear war” would be unimaginably worse than that of the hibakusha.

In the 1990 book Hiroshima: Three Witnesses, which contains the writings of three hibakusha, the editor and translator Richard Minear describes these personal accounts as “their Hiroshimas”. Without such accounts, he adds, “we know little of the human truth of Hiroshima. And without the human truth of Hiroshima, we know little of Hiroshima.” The same can be said of Nagasaki, and Southard’s book is one way for us to know a little more of its human truth.

- 2015 Souvenir Press/Viking £20.00/$28.95hb 416pp