An international group of astronomers has found new evidence that most of the energy in the Universe is in the form of "dark energy". Kyu-Hyun Chae of the University of Manchester and colleagues in the US, Germany and the Netherlands studied “gravitational lenses” found in the ten year Cosmic Lens All Sky Survey (CLASS). By combining the results of the survey with data on the distribution of galaxies, they showed that most of the energy in the universe is in the form of dark energy (KH Chae et al. 2002 Phys. Rev. Lett. 89 151301)

If the actual energy density in the universe is less than a certain value, the critical density, then the universe will continue to expand forever. If the actual energy density is more than the critical density, the universe will eventually stop expanding and begin to collapse under the influence of gravity. Astronomers believe that the actual energy density is equal to the critical density, and this has been confirmed by measurements on the cosmic microwave background — the radiation left over from the big bang.

However, ordinary matter and “dark matter” – matter that we cannot see but which nevertheless exerts a gravitational influence on stars and galaxies – can only account for about a third of the critical density. “Dark energy” is the name given to the remaining two thirds of the energy density – yet no one knows what it is.

Dark energy is unlike gravity in that it repels matter and therefore causes the expansion of the universe to accelerate. The first evidence for dark energy came from supernovae observations in 1998 and further evidence arrived earlier this year from a survey of 250,000 galaxies. The latest evidence comes from observations of gravitational lensing.

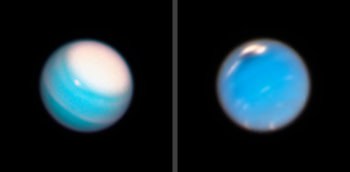

Gravitational lensing occurs when the light from a distant object, such as a quasar, is bent by the gravitational field of another object on its journey to Earth. Chae and co-workers used three major radio telescopes, the Very Large Array in New Mexico, the National Radio Astronomy Facility in the UK and the Very Long Baseline Array in the US, to search for the gravitational lensing of radio waves from distant quasars.

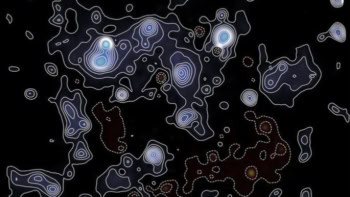

Chae and co-workers then combined the CLASS statistics with the latest results from galaxy surveys. They noticed that the effective lens size of galaxies was smaller than previously thought. For this result to be compatible with measurements from galaxy surveys requires the presence of a large amount of dark energy in the universe.

The group now plans to examine the individual gravitational lenses in more detail and a much larger radio survey is also under discussion.