Researchers in Israel have found the first evidence for natural heat pumps in living creatures. David Bergman and colleagues from Tel Aviv University used infrared imaging to show that wasps can sometimes remain much cooler than their surroundings. This is also the first time that the thermoelectric effect has been seen to play a role in the physiology of an animal (J S Ishay et al. 2003 Phys. Rev. Lett 90 218102).

Some wasps and hornets live in parts of the world where local temperatures can reach 60 oC or more. ‘Social’ wasps live in nests and regularly go outside to forage for food. During such activities the wasp produces heat that originates in its flight muscles and then spreads throughout the rest of its body. This should make the wasps even hotter but in experiments with oriental hornets Bergman and co-workers found that the internal body temperature of the wasps could be significantly cooler than the ambient temperature.

The Israeli workers argue that the insect must possess a heat pump, which works by using power generated from electrochemical reactions in its body. They believe that additional power is generated by the photovoltaic effect in the hornet’s shell. This means that an electrical current is produced when the shell is exposed to sunlight – in a mechanism similar to that in a semiconductor p-n junction when irradiated with visible or ultraviolet light. “This could explain how hornets remain active even on very hot summer days,” Bergman told PhysicsWeb.

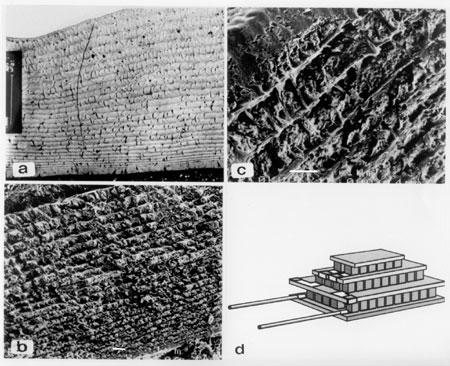

The researchers also took transmission and scanning electron micrographs of the shell. They observed a microstucture that was very similar to that of a practical thermoelectric heat pump – but on a different length scale (see figure).