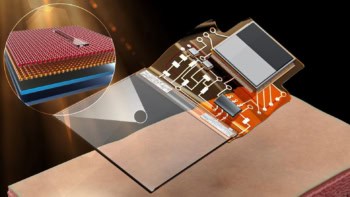

Two independent groups of researchers have taken important steps in overcoming friction in nanosized mechanical devices. A team from the University of Basel in Switzerland has shown that friction between the tip of an atomic-force microscope and a salt crystal can be cut 100-fold by applying a small vibrating force normal to the interface. Meanwhile, another group from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California has found a way to control friction in a similar set-up using electric fields.

Friction is a big problem in nanosized devices because they have huge surface-to-volume ratios, which means that their surfaces quickly wear out and seize up. Traditional lubricants are useless in such machines because they become thick and sticky when confined in such tiny enclosed spaces. Scientists therefore need to learn how to conquer friction if nano- and microscale devices are ever to become a commercial reality.

In the Swiss experiment, Anisoara Socoliuc of the University of Basel in Switzerland and colleagues formed a contact between a sharp silicon tip and an atomically flat surface made of sodium chloride. When the salt crystal is moved, the tip sticks and slips in a series of instabilities. However, when the researchers applied a sinusoidally varying tensile force between the tip and the crystal, the instabilities were surpressed, reducing friction by more than a 100 fold (Science 313 207). This is because the varying force reduces the peaks and troughs in the potential-energy landscape between the tip and the surface.

In the other experiment, Jeong Young Park and co-workers at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California dragged a microscope tip over a silicon substrate that has well defined n- and p-doped regions (Science 313 186). They found that applying a voltage of +4V to the surface doubled the amount of friction in the p-doped region. Although friction went up, not down, the researchers say the effect could still be a useful control mechanism in real nanoscale devices, where it is easy to apply voltages of this size. However, the team does not know why the increase occurs.