A US firm claims to have sent commercial levels of electric current down long (100 metre) lengths of "second generation" high-temperature superconducting wire for the first time. American Superconductor says that its breakthrough achievement could speed up the acceptance of high-temperature superconductor technology in the market place. The firm's second-generation wire -- made from yttrium, barium copper and oxygen (YBCO) -- is cheaper to manufacture and retains its superconducting abilities better under magnetic fields than "first-generation" wire.

Superconductors are materials that lose their electrical resistance when cooled below a certain temperature. Most superconductors have transition temperatures of just a few Kelvin, but in the mid-1980s a new class of high-temperature superconductors with transition temperatures of up to 100K was discovered. These high-temperature “cuprate” superconductors conduct electricity without resistance simply by cooling them with liquid nitrogen.

First-generation HTS wires — made from bismuth, strontium, calcium copper oxide (BSCCO) — have been on the market for some time and can carry up to 100 times the current in standard copper wire of the same size. But because these wires cost more than 100 times as much to make, they have not been a huge success in the marketplace.

Second-generation wires, first invented by researchers in Japan and the US over 10 years ago, have been more promising. Unfortunately, YBCO is not an easy material to work with because it forms an array of grains as it is deposited on a substrate, the boundaries between which have to line up exactly so that pairs of electrons can flow from one grain to the next.

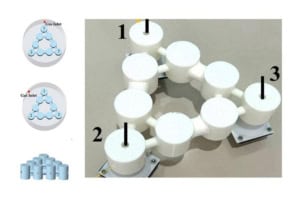

American Superconductor has now been able to make ribbon-shaped YBCO wires that are 100 metres long and just 4-mm wide. It made them by depositing YBCO onto a substrate of nickel alloy, which has highly aligned grains that the YBCO grains can in turn follow. The firms says its wires can carry a current of up to 140 Amperes when cooled with liquid nitrogen — about 150 times as much as a standard copper wire of the same dimension. “Just one of these wires would be able to carry enough power to serve the needs of approximately 1000 homes,” says Alex Malozemoff, the firm’s chief technical officer.

The new wires could be used for power transmission and distribution cables, propulsion motors, power regulators and fault current limiters as well as in prototype power cables, maglev trains and MRI. The company says it has already shipped nearly 3000 metres of the new wire to its customers this year and expects to scale up production to 10,000 metres by the end of 2007.