Physicists in the US claim to have doubled the 42 GeV electron-beam energy of the three-kilometre-long Stanford Linear Accelerator Centre (SLAC) by simply adding a metre-long device on the end. The device, which uses a plasma wakefield to accelerate a small fraction of the electron beam, could allow conventional particle accelerators to reach higher energies (Nature 445 741).

By the time CERN’s Large Electron-Positron (LEP) collider was dismantled to make way for the forthcoming Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in 2000, it had pushed the record for accelerated electron energies over 100 GeV. But such energies are not easy to come by, and the LHC will come with a final price tag of about $8 billion.

Now, Mark Hogan and his team from the SLAC and two Californian universities have shown that devices based on “plasma wakefields” – a much smaller and potentially cheaper technology – can supplement existing, conventional accelerators by “turbocharging” the particles as they leave. They have developed a device just 85 cm long that took the 42 GeV electron beam at SLAC up to 85 GeV.

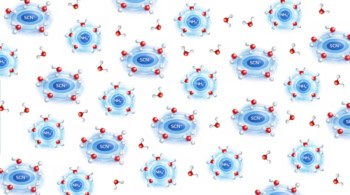

Recently, physicists have accelerated electrons to GeV energies in plasma wakefields created by firing a laser into a jet of gas. Hogan’s team, on the other hand, used the electron beam from SLAC as an input for their device, which was filled with lithium vapour. Electrons from the gas were dragged away from the lithium nuclei by the beam, only to snap back and overshoot their initial position. This oscillating movement, which occurred in the wake of the original electron pulse, occasionally captured some of the pulse’s electrons and accelerated them to much higher energies.

Because SLAC’s beam contained compressed bunches of electrons, Hogan’s device could maintain a stable accelerating wakefield for almost a metre. Previous devices have been limited to a few centimetres by a beam instability known as “hosing”, named after a similar effect in cartoons when untamed hosepipes thrash about as water is pumped through them.

However, several challenges remain before the technique can be used in practical particle accelerators. The team now need to reduce the energy spread of the electrons, and prove that positrons can also be accelerated in the same manner. “The problem with plasmas is that they’re nearly always unstable,” Robert Bingham, a physicist at Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, told Physics Web. “This [result] leads the way to build longer plasma columns and hence produce higher energy particles.”