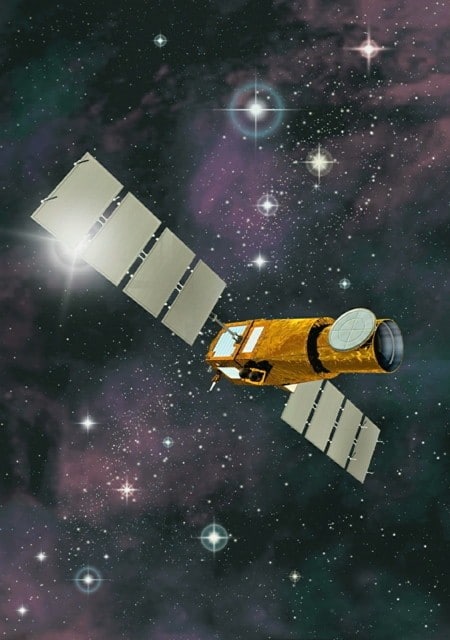

COROT, the first space observatory designed to search for planets beyond our solar system (exoplanets), captured its "first light" yesterday. Engineers from France's Space Agency CNES sent a command to open the hatch protecting the 30-cm telescope, exposing its extremely sensitive charge-coupled device (CCD) arrays to the stars. Launched into Earth orbit about three weeks ago, the spacecraft will look for exoplanets around 60 000 stars in two regions of our galaxy.

Astronomers have already discovered more than 200 exoplanets using ground-based telescopes or general-purpose space telescopes like Hubble. Most of these are large, gaseous planets, sometimes called “failed” stars, about the size of Jupiter and Saturn. Exoplanets are found by looking for minute dips in the brightness of a star when the exoplanet passes in front of it. Turbulence in Earth’s atmosphere makes it extremely difficult for smaller, rocky planets, like Earth, to be detected in this way from the ground. As a result, only a handful of rocky planets have been discovered so far.

COROT, however, is 900 km above Earth’s atmosphere, where its CCDs can detect changes in star brightness as small as 0.01%. This is about 100-times better than the best ground-based telescopes. Still, planets the size of Earth will probably escape detection, but the craft should be able to spot planets twice Earth’s size circling stars like the Sun. Unlike large gaseous planets, these rocky planets are more likely to harbour life.

Of the four CCD arrays, two are dedicated to measuring seismic oscillations in stars. Just like the Sun, many stars vibrate, and these vibrations can be observed as small periodic fluctuations in their brightness. These fluctuations occur on timescales ranging from seconds to hours and provide information about the star’s mass and internal structure.

CNES has already performed a successful in-orbit testing and calibration of COROT’s CCD arrays. This was done in the dark with the help of flashes from light-emitting diodes. Now, astronomers can do more tests using starlight. Annie Baglin of the Observatory of Paris at Meudon and COROT’s principal investigator told Physics Web, “Everything worked out fine. We are starting to see stars… We will need a few months for further calibrations before we can present data to the public.”