Astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope may have solved the mystery of how the Milky Way continues to spawn new stars at a consistent rate despite its diminishing gas reserves. They say the galaxy is being supplied by clouds of gas originating from outside of the Milky Way, and that these findings could help refine our knowledge of galaxy evolution.

The Milky Way currently converts 0.6–1.45 solar masses’ worth of gas into new stars every year, depleting the galaxy’s gas reserves. Yet the star formation rate doesn’t seem to be dropping, which suggests that something must be replenishing the supply. Ionized High Velocity Clouds (iHVCs), fast-moving conglomerations that move with a haste that cannot be explained by the rotating disc of the galaxy, are a proposed culprit. One suggestion is that they could be remnants from the formation of the 30+ galaxies in the Local Group, drawn in by the Milky Way’s gravity. If they do originate beyond the galactic disc, and then fall onto it, they could be bolstering the amount of gas in the galaxy.

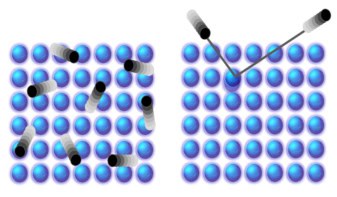

It is not clear how large these clouds are but they were first found when astronomers noted that some of the light from distant quasars was being absorbed by objects near the edge of the galaxy. However, the huge distances involved meant it was unclear whether the iHVCs were directly associated with the Milky Way’s halo – the diffuse sphere that surrounds the galaxy – or existed beyond it. In order to solve this problem, Nicholas Lehner and Jay Christopher Howk, of the University of Notre Dame, US, adapted the quasar technique.

“Instead of observing quasars, we observed stars within the Milky Way’s halo”, Lehner told physicsworld.com. The pair observed 28 halo stars with the Hubble Space Telescope, 14 of which showed similar absorption lines in their spectra to the original quasars observations – the presence of an iHVC was revealed. The distance to these stars is well known, and so gives the maximum possible distance of the iHVC that has now been incorporated into the galaxy.

Why doesn’t the galaxy run out of gas?

Knowing the distance is the first piece in a jigsaw. “The mass of the iHVC is proportional to the distance squared,” explains Lehner. Lehner and Howk then used the original quasar observations to model the likely distribution of these iHVCs across the sky. Knowing where they are, how much gas they contain and how fast they are moving allowed the pair to estimate how much gas should fall on the Milky Way per year. “We predict that between 0.8 and 1.4 solar masses of material from iHVCs falls onto the Milky Way annually,” says Lehner. Compare that to the 0.6–1.45 solar masses consumed in star formation every year, and there is a potential answer to why the galaxy doesn’t run out of gas: it is commandeering it from intergalactic space.

“They found the magic number,” Filippo Fraternali, who researches iHVCs at the University of Bologna, Italy, told physicsworld.com. “It is not 0.1 or 100 solar masses in-filling each year, but very close to one – this is an important result,” he adds. However, the result isn’t water-tight. “It is the right approach, but there are big assumptions that may change that final number quite a bit,” Fraternali explains. He would like to see a much bigger sample than the original 28. “It is hard to get good statistics on a sample of that size,” he says.

Now that they are confirmed halo objects, Lehner is planning just that. “We’re going to go back to the quasar database, which is much larger than our stellar sample,” he explains. “If we want to understand how galaxies evolve then we need to understand how this gas gets in and out of them,” he adds.

This research was published in Science.