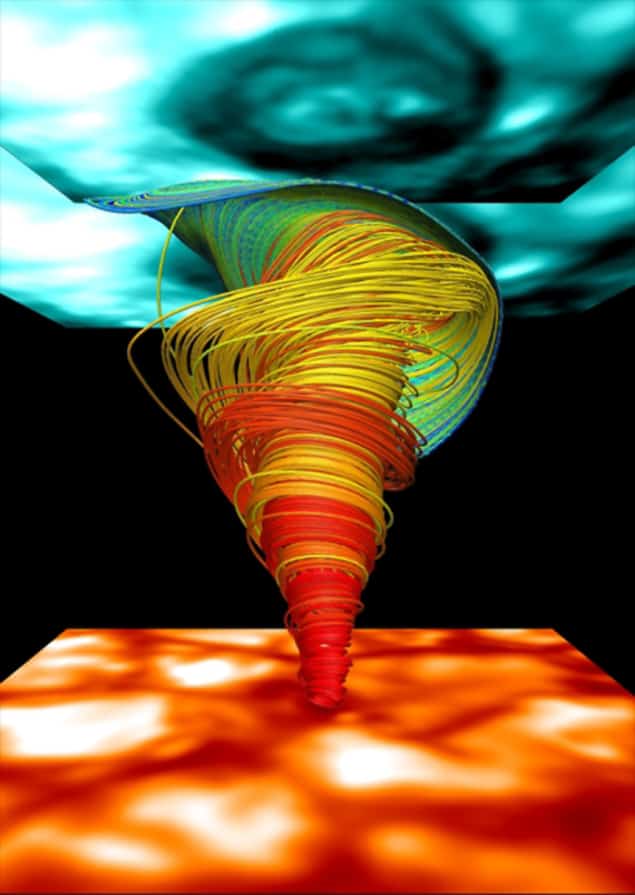

Giant tornado-like structures with diameters exceeding the width of the United States have been identified in the Sun’s outer atmosphere, the corona. The discoverers say the twisters might provide a mechanism for the transfer of energy within the Sun, which could help to explain a longstanding mystery of why the Sun’s corona is drastically hotter than its surface.

The corona is a region of ionized gas that extends millions of kilometres from the surface of the Sun into space. Physicists have known for more than half a century that it has a temperature of several million kelvin, while the solar surface is a relatively mild 6000 K. This surprising feature of the Sun has challenged astrophysicists, who are yet to directly observe the mechanism by which the corona is heated.

But new opportunities to observe the Sun – and the processes involved in the transfer of energy between solar layers – are being provided by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), launched in 2007. Data from one of SDO’s scientific instruments called the Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA), has been analysed in this latest work by a group of researchers at the University of Oslo in Norway, led by the astrophysicist Sven Wedemeyer-Böhm.

Speedy twister

Wedemeyer-Böhm’s group has found within the AIA data evidence of swirls of gas in the corona that resemble tornadoes. The twisters have diameters between 1500 and 5500 km, and some are ring-like while others have spiral arms. Each tornado event identified lasted for a few minutes as coronal gases with temperatures of around one million kelvin were rotated at speeds in excess of 10,000 km/h.

Earlier studies have revealed that the Sun’s surface is also covered with vortex flows of gas due to thermal instabilities in the underlying layers. Wedemeyer-Böhm’s team believes that the solar tornadoes are connected to these surface vortices by the Sun’s magnetic field. The team’s idea is that magnetic flux emerging from the Sun’s interior is forced to twist as it passes through the solar surface, leading to the generation of tornadoes in the overlying layers.

In a paper in Nature this week (486 505), the researchers describe how they have identified 14 super-tornadoes and they estimate that more than 10,000 of them exist at any one time in the sections of the Sun that are magnetically quiet. The upper boundaries of individual tornadoes have been spotted at varying elevations in the corona, but the length of each tornado must be at least 2000 km – the typical distance between the corona and the solar surface.

Fuelling the corona

By combining their observations with numerical simulations of the Sun’s outer layers, the researchers propose that these magnetic tornadoes can provide a mechanism for transferring heat to the corona. “The tornado as we see it extends from the surface through the chromosphere into the corona. It is really strongest in the chromosphere but releases the energy in the corona above,” Wedemeyer-Böhm told physicsworld.com. He acknowledges, however, that the tornadoes probably do not account for all of the energy transfer. “It may most likely not account for all of the required energy in quiet regions but probably for a good portion of it.”

Indeed, a separate group published a paper last year based on data from NASA’s AIA instrument, which also presented a potential mechanism for the transfer of heat to the corona. This group led by Scott McIntosh of the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, identified in the corona an abundance of a phenomenon called Alfvénic waves. These waves – predicted by the Swedish Nobel laureate Hannes Alfvén – were detected in short-lived jets of gas in the corona known as spicules, which are significantly thinner than the tornadoes identified in this latest work.

McIntosh believes that the newly identified tornadoes could represent a large-scale manifestation of Alfvénic waves. “Almost any form of pulling, pushing, tweaking, twisting or pinging will drive wave energy upward into the atmosphere and they are all flavours of Alfvénic motion,” he says. “What is reported in this article is a form of that motion, but on a larger coherent length scale.”

In search of more twisters

Looking to the future, Wedemeyer-Böhm says his group will try to work out the amount of coronal heating accounted for by these tornadoes. It will do so by analysing more data from the AIA instrument and developing its numerical models.

Peter Cargill, a space and atmospheric physics researcher at Imperial College, London, is impressed by the scope of the research. “The main thing I come away with is the impression of how much information comes from an analysis of the solar atmosphere using data from as many different layers as are available and how numerical models can help interpret the data.”

Cargill feels, however, that there are still many unanswered questions concerning the transfer of energy between the corona and the solar surface. “You might ask whether these tornadoes exist over multiple scales, what is the distribution of injected energy in them, and similar questions for waves, braiding, spicules and so on”.