Optical “nanotweezers” that can grasp and move objects just a few tens of nanometres in size have been created by researchers in Spain and Australia. The new tool is gentle enough to grasp tiny objects such as viruses without destroying them, and works in biologically-friendly media such as water. The nanotweezers could find a range of uses, from helping us to understand the biological mechanisms underlying diseases to assembling tiny machines.

Controlling the placement of individual molecules is critical in medicine, for example, where investigating the origin of diseases often requires manipulating viruses or large proteins. The accurate placement of tiny objects such as carbon nanotubes is also expected to play an important role in the development of nanotechnologies such as molecular motors and other tiny devices.

Beating the diffraction limit

While nanometre-sized objects can be moved around using conventional optical tweezers, the precision to which this can be done is subject to the diffraction limit – about 300 nm for visible light. However, this limit does not apply to near-field light waves. These exist near light-emitting regions and drop rapidly in intensity across distances that are much smaller than the diffraction limit.

In the 1990s some researchers suggested that a near-field scanning optical microscope could be capable of trapping and manipulating objects as small as a few nanometres. This type of microscope captures near-field light by scanning a tiny aperture – usually tens of nanometres in diameter – just a few nanometres above the object of interest.

Too hot to handle?

Turning such a microscope into optical tweezers involves firing laser light through the aperture, thus focusing it to a tiny spot of near-field light. As in current optical tweezers, the intensity gradient of the light across the spot draws tiny dielectric objects to the spot’s centre, where the electric field is strongest. In principle, this could allow tiny objects to be held and manipulated with nanometre precision. However, experimental tests of this technique were never done because of the concern that the concentrated light at the tip of the microscope would be so intense that it would damage heat-sensitive objects or even the microscope tip itself.

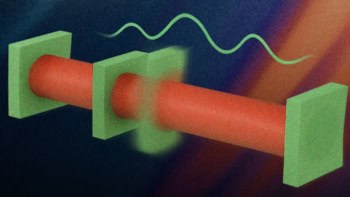

Now, Romain Quidant at the Institute of Photonic Sciences in Barcelona and colleagues have shown that tiny objects can be successfully trapped and manipulated using light of much lower intensity than had been contemplated in earlier designs. The team’s set-up involves a 1-μm-diameter optical fibre with an 85-nm-wide bow-tie-shaped aperture milled into its end (see image above).

A firm handshake

Quidant and colleagues reduced the intensity using a new technique called self-induced back action (SIBA) trapping that relies on adjusting the local field intensity in real time, based on the behaviour of the specimen. “The trapped object plays an active role in the trapping mechanism,” says Quidant. He explains that the trapping process is like a firm handshake that neither crushes nor releases the object. This method reduces the intensity of light needed to hold the object by several orders of magnitude, which removes the possibility of damage to the tip or object.

Quidant and colleagues used a near-infrared laser the power of which could be modulated between 2–5 mW. The researchers showed that polystyrene beads 50 nm in diameter – about the size of the virus that causes yellow fever – suspended in water could be successfully trapped and held for longer than 30 min. As well as firing the laser down the fibre so that light emerged from the aperture, the team also looked at an alternative set-up in which the laser was shone through an external lens that focused it onto the aperture. However, the researchers concluded that this external illumination configuration was inferior because the position of the aperture had to be fixed, which limited the mobility of the sample.

“We foresee this technique could become a universal tool in nanoscience, in any research where the non-invasive manipulation of nano-objects would be required,” says Quidant.

The nanotweezers are described in Nature Nanotechnology.