Three Roads to Quantum Gravity

Lee Smolin

2000 Weidenfeld and Nicolson 196pp £16.99hb

There is one central quandary to 21st-century physics. It is that the two main pillars of 20th-century physics – quantum mechanics and Einstein’s general theory of relativity – are mutually incompatible. On the sub-atomic scale, Einstein’s view of gravity fails to comply with the quantum rules that govern the elementary particles, while on the cosmic scale, black holes are threatening the very foundations of quantum mechanics. “Quantum gravity” is the name we give to the solution to this problem, but the way to achieve it and the question of whether such a solution even exists are the subjects of hot debate. Three Roads to Quantum Gravity by Lee Smolin is a layperson’s guide to the different routes on which today’s theorists are currently embarked.

Smolin has himself worked in the field of quantum gravity for the last 25 years, but it is fair to say that his ideas have always remained outside the mainstream. This book is no exception. Indeed, the “true heroes of this story” are not the names that most practitioners would have chosen, such as Ed Witten or Stephen Hawking, but rather other mavericks such as Alain Connes, David Finkelstein, Chris Isham, Roger Penrose and Raphael Sorkin.

So the reader should be aware that Smolin’s views are highly idiosyncratic and are by no means representative of current thinking. This said, the book is written in the same lively, anecdotal and readable style that those familiar with his previous book, The Life of the Cosmos, will have come to expect (see “Holes in a final theory?” Physics World December 1997 pp39-40).

The first of the three roads that Smolin identifies is superstring theory and its successor, M-theory. According to superstring theory, the fundamental building blocks of nature are not point-like elementary particles, but tiny one-dimensional strings that live in a universe with one time dimension and nine space dimensions. Just like violin strings, these relativistic strings can vibrate, with each mode of vibration representing a different elementary particle. Most importantly, these stringy particles include gravitons, the hypothetical carriers of the gravitational force.

Indeed, superstrings satisfy one of the main requirements of a consistent quantum gravity: we can calculate the probability of transitions from one quantum state to another involving gravitons without encountering the infinities and anomalies that have plagued all previous attempts based on applying ordinary quantum field theory to Einstein’s general relativity. Superstrings nevertheless subsume Einstein’s theory, in that it is recovered in the limit where the energy of the gravitons is sufficiently small. Moreover, the superstring equations admit solutions for which six of the nine dimensions are curled up to an unobservably small size so that the theory is compatible with our everyday experience of a world with only three space dimensions.

Unfortunately, there is not one but five mathematically consistent superstring theories, each competing for the title of the “theory of everything”; clearly an embarrassment of riches. This problem is cured by M-theory, a unique all-embracing theory that subsumes the five superstring theories by requiring eleven space-time dimensions and incorporating higher-dimensional extended objects called membranes.

Among the achievements of M-theory is the first microscopic explanation for the entropy of a black hole, first predicted in the 1970s by Stephen Hawking using macroscopic arguments. There is a cautionary tale here. In the years between the superstring revolution of 1984 and the M-theory revolution of 1995, the mavericks who advocated eleven dimensions and membranes were scoffed at by the orthodox superstring theorists. So perhaps we should be more tolerant of Smolin’s version of unorthodox speculations – although some of them, such as the formation of new universes inside black holes, will take some swallowing.

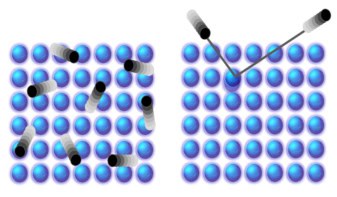

The second road Smolin describes is “loop” quantum gravity, the road that he himself walked for many years (see “The new universe around the next corner” by Lee Smolin Physics World December 1999 pp79-84). According to this picture, if we were to probe space-time at very small length scales, we would discover that it is not the smooth Riemannian geometry of general relativity but quantized in tiny discrete volumes. The theory grew out of an idea in quantum chromodynamics (QCD), the accepted theory of the strong nuclear force.

In a version of QCD due to Kenneth Wilson, the fundamental entities are not fields but loops. Smolin and others attempted a Wilson-loop description of gravity. Their motivation was to get away from the idea of fundamental quantum processes taking place in a fixed-background space-time and allow the space-time to be part of the quantum dynamics.

Critics of this approach will argue that although there is nothing wrong with Wilson loops as a calculational technique, it must be applied to the right equations if it is to get anywhere. And although QCD no doubt provides the right equations of the nuclear force, the right theory of quantum gravity has to go beyond the 1916 Einstein equations upon which loop quantum gravity is based. Perhaps not surprisingly, Smolin’s attitude is more forgiving, and he advocates a synthesis of these ideas and string theory.

The third road, trod only by the heroes, involves “wrestling with the fundamental principles” and questioning the foundations of thought and even of mathematical logic.

There is always a danger when following this road that it can easily become so nebulous as to invite the famous put-down of Wolfgang Pauli: it is not even wrong. To say that the final theory will be completely different from what we have now, with concepts we have not yet even dreamed of, is an empty truism. Much more can be learned from a concrete proposal, however flawed, than from a sterile contemplation of the quantum-gravity navel. Smolin is not one to heed such warnings, however. The more he can feel that his musings are “deep”, “profound” and “philosophical”, the happier he is.

Read this book. You will be informed, provoked and sometimes irritated – but always amused.