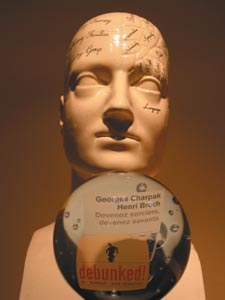

Debunked!: ESP, Telekinesis and Other Pseudoscience

Georges Charpak and Henri Broch

2004 Johns Hopkins University Press 176pp £17.00/$25.00hb

The trouble with discussions of paranormal phenomena is that opinions are always polarized, with physicists generally lying in the dismissively sceptical camp. Most of the rest of society – with the possible exception of fellow scientists – tends to have views that range from “firm believer” to “one must keep an open mind on these issues”. This polarization leaves little room for dialogue.

Sceptics are unlikely to be able to contribute to an informed debate because they do not have enough knowledge of the topics that they have rejected as nonsense. And arguments based on purely theoretical grounds are generally ineffectual, given that some phenomena that are now widely accepted – such as meteorites and plate tectonics – were once also dismissed for similar theoretical reasons. In my view (and as an experimental physicist perhaps I am biased) sceptics must deal with the evidential basis for paranormal phenomena where appropriate. But we should also be able to suggest reasonable alternative explanations for apparently extraordinary phenomena.

Debunked! written by French Nobel laureate Georges Charpak and fellow physicist Henri Broch is a valiant attempt to arm readers with some of the weapons necessary to contribute to this debate. The title of the original French edition of the book – Devenez Sorciers, Devenez Savants – better encapsulates the authors’ philosophy than does the English title. “By learning to fool others,” the authors suggest, “you will be better prepared to judge the blandishments of the merchants of deception, who try to persuade you of their special and extraordinary knowledge, whether it’s in the area of health, love or politics. Remain scientists – and become sorcerers!”

Charpak and Broch cover a number of topics, including telepathy, metal-bending, astrology, coincidence, fire-walking and dowsing. They even stray into areas such as the public perception of the dangers of nuclear power. An important aspect of the book is its attempt to enable readers to devenir sorciers – become sorcerers – by exposing a number of conjuring tricks used by certain latter-day proponents of the paranormal. After finishing this book, the reader should be able to demonstrate telekinetic metal-bending, push sharp objects through body parts, and read minds at a distance. (With the aid of the memory alloy Nitinol, a good mechanical workshop, and a confederate, respectively.)

The section on dowsing is particularly useful, given that this is the one area where physicists tend to move from the sceptical to the gullible camp. The authors discuss some of the numerous blind experiments that have been done on dowsing. Readers who believe that they have water-divining abilities should contemplate setting up a blind experiment of the type described in the book, in which water is allowed to run through one of a number of (preferably buried) pipes.

All the dowser has to do is to determine the pipe in question. To the total surprise of the practitioners, such experiments have yielded – and will continue to yield – results that can only be attributed to chance.

I strongly agree with the authors that many ordinary phenomena are regarded as extraordinary because most of us lack an intuitive understanding of probability and statistics. For instance, if we were to guess the probability that an individual, on any particular night, dreams of an aeroplane crash, we might come up with a number between one in a few thousand and one in a million. On any given night, therefore, perhaps between 60 and 6000 people in the UK dream of such an event. So far, entirely unsurprising. But if a catastrophic air accident does occur in the day following the one night in my life that I dream of a plane crash, this statistically insignificant event may give me an unshakeable, lifelong conviction that I have experienced a precognitive dream. This theme is explored effectively and at some length in the chapter entitled “Amazing coincidences”.

The section on fire-walking is less well done. Although the authors correctly identify the factors that enable anyone to walk on hot coals without injury – including coal’s low heat capacity and poor thermal conductivity – they begin by focusing on the spheroidal shape of water droplets, which they themselves acknowledge as having little relevance to fire-walking. This just confuses the reader.

Overall, this is a somewhat quirky book that provides a fairly uneven coverage of pseudoscience and the paranormal. For a more comprehensive coverage of these topics, I would recommend Pseudoscience and the Paranormal by Terence Hines (2003 Prometheus) or The Psychology of the Psychic by David Marks and Richard Kammann (1994 Prometheus).

On the other hand, Debunked! does have a certain Gallic charm, particularly in the way in which it is written – to such an extent that I bought the French version of the book to see if the quaint language was present in the original. Even on fairly factual topics, French writers seem to prefer a much more literary style than their British or American counterparts, and translator Bart K Holland has done a fair job of rendering the text into English. Nonetheless, sentences such as “Now we are going to set sail amid islands of ignorance, which are perfectly well charted in any good atlas of superstition – and which are objects of veneration and pious pilgrimages nonetheless” do take a little digesting by someone more used to prosaic English text.

Despite these reservations, I enjoyed reading this book (in two languages) and was particularly interested to learn about purportedly paranormal events that have not been covered elsewhere, such as the mysterious sarcophagus at Arles-sur-Tech. For centuries this marble tomb has been miraculously accumulating water, without plumbing or any other obvious source. However, for the price of the book in the UK or the US, it is possible to buy a paperback version of the original French edition (for just €5.70), a good French/English dictionary, and still have enough left over to buy a dowsing rod and a couple of Nitinol teaspoons.