Strings

Carole Buggé

January 2007

78th Street Theatre Lab, New York, US

Can there be too many science metaphors in a play for even a physicist reviewer? That was the question I found myself asking while watching Strings, a new physics-based play that opened for a three-week run over Christmas in a small theatre in New York City. The witty and enjoyable play was written by US novelist Carole Buggé and starred a competent cast of experienced actors. The storyline involves three physicists on a train journey from Cambridge to London, who, in a self-referential touch, are going to see a performance of Michael Frayn’s own intellectual science play Copenhagen.

The three travellers in Strings are the upper-class cosmologist George (Keir Dullea, best-known as Dr Dave Bowman in the film 2001: A Space Odyssey), his mountain-climbing physicist wife, June (Mia Dillon) and a brilliant working-class string theorist, Rory (Warren Kelley), who is also June’s lover and George’s friend. The programme notes that the play is loosely based on a real train journey made by three physicists: the Americans Burt Ovrut and Paul Steinhardt; and the South African Neil Turok. During that journey the three hammered out their “ekpyrotic” theory of the origin of the universe, in which the Big Bang is caused by a collision between the extradimensional “branes” that appear in string theory.

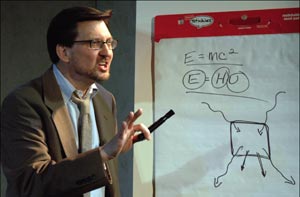

The complex relationships between George, June and Rory are time and again compared metaphorically to principles in science, from June being shared like an electron between atoms in a covalent bond, to George as a neutral neutron and Rory a positive proton. Many other concepts from modern physics are employed by Buggé, but they are awkwardly presented almost as lectures in a classroom – at times even including a flip chart. These include the famous Schrödinger’s cat thought experiment, wave–particle duality, the unification of the four fundamental forces, and the “spooky action at a distance” implied by quantum mechanics. Each time the actors were called on to explain rather than embody the physics, they and the audience seemed uncomfortable.

The three characters of Strings each share a scene with a physicist from the past: George discusses gravity and curved space–time with the comically foppish Isaac Newton (Drew Dix); June speaks to Marie Curie (Andrea Gallo) about radioactive decay and Curie’s loss of her beloved husband Pierre; and Rory idolizes Max Planck (Kurt Elftmann) for resolving the ultraviolet catastrophe in the classical description of black-body radiation in 1900 and thus ushering in the new era of quantum mechanics.

While quantum mechanics has been experimentally verified, allows new phenomena to be predicted, and has played a major role in technological development, string theory has been criticized for doing none of these things. Whether the brane-collision theory of the Big Bang proposed at the beginning of the 21st century will turn out to be a significant step towards an ultimate theory of everything thus remains to be seen.

The play Copenhagen that the three companions are going to see – as were Ovrut, Steinhardt and Turok – is based on an actual meeting in 1941 between Werner Heisenberg and his mentor Niels Bohr in Nazi-occupied Denmark. Copenhagen also involves three characters: Heisenberg, Bohr and his wife Margrethe. Frayn presents various possible versions of the meeting, focusing on the question asked in the play by Heisenberg “Does one as a physicist have the moral right (during wartime) to work on the practical exploitation of atomic energy?”. Frayn’s play is more successful because rather than lecture the audience on the science, he employs subtle dialogue, allowing the non-scientist Margrethe to stand in for the lay audience.

The human issues in Strings, besides infidelity, centre on George’s belief in God and the loss of George and June’s son in the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center. In another reference to Copenhagen, this incident parallels the loss of the Bohrs’ son Christian in a boating accident. June’s grief is tinged by guilt that she was not caught in the building’s collapse herself because of accidental delays in meeting her son that fateful morning. If she could only have died with him, she laments. Even better, could she – and physics would seem to allow it – replay the event in a parallel universe with a better outcome? Buggé’s creativity in Act 2 allows for a parallel universe, with playful symmetry to scenes in Act 1.

Buggé is to be congratulated for taking the time to learn the science, and in most cases getting it correct, but she could have improved the development of the characters and their relationships. Rory is the best-written character, while we know little about June’s background other than that she (like the US physicist Lisa Randall) has worked on extradimensional theories of gravity. It seems to this reviewer that a tighter one-act play omitting the didactic lecturing would be an improvement.