Terminology from quantum theory shows up frequently in popular culture — from art and films to sculpture and poetry. Robert P Crease asks for your favourite examples

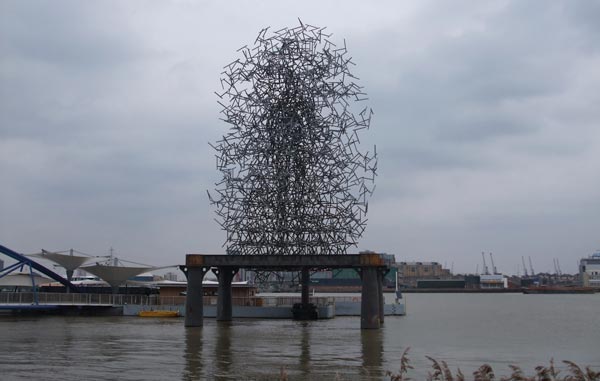

Its name is Quantum Cloud. Visitors to London cannot miss it when visiting the park next to the Millennium Dome or taking a cruise along the Thames. It rises 30 m above a platform on the banks of the river, and from a distance looks like a huge pile of steel wool. As you draw closer, you can make out the hazy, ghost-like shape of a human being in its centre. It is a sculpture, by the British artist Antony Gormley, made from steel rods about a metre and a half long that are attached to each other in seemingly haphazard ways. Framed by the habitually grey London sky, it does indeed look cloud-like. But “quantum”?

The word quantum has a familiar and well-documented scientific history. Max Planck introduced it into modern discourse in 1900 to describe how light is absorbed and emitted by black bodies. Such bodies seemed to do so only at specific energies equal to multiples of the product of a particular frequency and a number called h, which he called a quantum, the Latin for “how much”. Planck and others assumed that this odd, non-Newtonian idea would soon be replaced by a better explanation of the behaviour of light.

No such luck. Instead, quantum’s presence in science grew. Einstein showed that light acted as if it were “grainy”, while Bohr incorporated the quantum into his account of how atomic electrons made unpredictable leaps from one state to another. The quantum began cropping up in different areas of physics, then in chemistry and other sciences. A fully fleshed out theory, called quantum mechanics, was developed by 1927.

Less familiar and well documented, though, is quantum’s cultural history. Soon after 1927 the word, and affiliated terms such as “complementarity” and “uncertainty principle”, began appearing in academic disciplines outside the sciences. Even the founders of quantum mechanics, including Bohr and Heisenberg, applied such terms to justice, free will and love. Quantum has made unpredictable leaps to unexpected places ever since. The next James Bond film, for example, is to be called Quantum of Solace.

The quantum moment

The dean of my university at Stony Brook, James Staros, who is a scientist, sometimes refers to his faculty as being “quantized”. When budgets need to be cut, for example, he points out that it is impossible to reduce one department by, say, 0.79 positions and another by 1.21 positions, even if those numbers are perfectly proportionate to the cut. As Staros explains, “it has to be one from each, even if the departments are somewhat different in size”. This is a precise and effective rhetorical use of quantum language.

And when I asked Gormley about his sculpture’s name, he gave me a cogent response. “The development of quantum mechanics,” he told me, “represents the shift in science from the study of even more discrete entities to increasing attention to flow and field phenomena in which emergent forms are seen as evolving out of their contexts. Quantum Cloud evokes this.”

While both Gormley and Staros deploy quantum language in a fairly precise fashion, on other occasions it is badly abused, bringing to mind James Clerk Maxwell’s observation that “the most absurd opinions may become current, provided they are expressed in language, the sound of which recalls some well-known scientific phrase”. The word quantum, for instance, appears regularly in pseudoscience, self-help and quack-medicine discourse.

Yet if we think scientifically rather than judgmentally, all uses of quantum language – whether precise or pretentious, technically correct or ill-informed and designed to impress – are interesting. After all, each is motivated by some conception of the meaning of the quantum. But what patterns can we find in those conceptions? And what do these patterns say about culture and how it understands science?

My colleague Fred Goldhaber and I have raised these questions in a course called “The quantum moment”, which we have given several times to students at Stony Brook. We stole the name from Mordecai Feingold’s book The Newtonian Moment: Isaac Newton and the Making of Modern Culture, which sprang from an exhibition at the New York Public Library in 2004–5 that examined Newton’s impact on the culture of the late 17th and early 18th%nbsp;century. In a similar vein, Goldhaber and I were keen to gauge what impact the word quantum has had on today’s culture.

We discovered that the answer is complicated, for quantum has spread across the world in various ways.

Pattern #1: irreducibly statistical processes

One pattern involves applying quantum terms to irreducibly statistical processes. For about a quarter of a century, physicists have applied mathematical constructs developed for quantum phenomena to economics. For example, in his book Quantum Finance: Path Integrals and Hamiltonians for Options and Interest Rates, physicist Belal Baaquie of the National University of Singapore notes that he is not applying quantum theory itself to finance. “Instead,” he writes, “the term ‘quantum’ refers to the abstract mathematical constructs of quantum theory that include probability theory, state space, operators, Hamiltonians, commutation equations, Lagrangians, path integrals, quantized fields, bosons, fermions, and so on. All these theoretical structures find natural and useful applications in finance.” The word quantum here refers not to quantization as such, but to the application of its statistical methods to stochastic processes such as interest rates and stock-price fluctuations.

For something completely different, consider Quantum Sheep, the brainchild of Valerie Laws, a writer who lives in the north of England. In 2002 she spray-painted words onto the fleeces of sheep from a nearby farm. As the flock milled about, the words rearranged and a new “poem” was created every time the sheep came to rest. A spokesperson for Northern Arts, which provided £2000 of funding for the project, said that the result was “an exciting fusion of poetry and quantum physics”. Here is one of the resulting “Haik-Ewes”:

Clouds graze the sky

Below, sheep drift gentle

Over fields, soft mirrors

Warm white snow

Talking to the BBC at the time, Laws explained why she felt the project was worth pursuing. “Randomness and uncertainty is at the centre of how the universe is put together, and is quite difficult for us as humans who rely on order,” she said. “So I decided to explore randomness and some of the principles of quantum mechanics, through poetry, using the medium of sheep.”

There is, of course, a world of difference between calculating interest rates and setting a herd of painted sheep loose in the countryside. But both of these cases were motivated by the role of randomness in quantum theory: the former case involves an actual use of its statistical methods, while the latter invokes quantum as a symbol of irreducibly random processes.

Pattern #2: complementary beer

Quantum Man is a sculpture by Julian Voss-Andreae currently installed in the City of Moses Lake, Washington (Physics World September 2006 p7; print version only). Made of steel sheets 2.5 m high that lie parallel to each other, the sculpture changes in form as you walk around it. From one perspective it reveals the outline of a human being, while from another the human form disappears entirely.

The sculpture, says the artist, is “a metaphor for the counterintuitive world of quantum physics”. Voss-Andreae should know. He studied physics as an undergraduate in Berlin and Edinburgh, and did graduate research in Vienna with Anton Zeilinger on the double-slit experiments involving the quantum interference of carbon-60 buckyball molecules (Physics World November 2006 p44; print version only).

The metaphor is thus grounded in complementarity, Bohr’s name for the fact that, in the quantum world, two features of a description can be necessary but mutually exclusive — a particle having a definite position and momentum being the standard example. However, Bohr and several other leading physicists of the time felt that complementarity could also be extended to areas other than physics, an idea that has often been ridiculed. Yet after reviewing some of Bohr’s applications of complementarity to the social world, one of Bohr’s biographers, the hard-nosed physicist Abraham Pais, found that while such applications were clearly metaphorical, they often helped him think “outside the box”. Pais declared that “Personally, I have found the complementary way of thinking liberating.”

I do not know how liberating Pais would have found the psychotherapist Lawrence LeShan’s more fanciful defence of mysticism in his book The Medium, the Mystic and the Physicist. Mystics seek the comprehension of a different view of reality, LeShan wrote, before adding that “I use the term ‘comprehension’ here to indicate an emotional as well as an intellectual understanding of and participation in this view…In physics this is called the principle of complementarity. It states that for the fullest understanding of some phenomena we must approach them from two different viewpoints. Each viewpoint by itself tells only half the truth.”

And while quantum terminology can be well grounded or fanciful, it can also be simply tongue-in-cheek. Take, for example, the Quantum Beer Theory website (wohlmut.com/beer) created by Kyle Wohlmut, a translator and dedicated beer fanatic who lives in the Netherlands. Wohlmut, who last studied physics in high school, explains that underlying his theory is the fact that “the essential experience of beer flavour arises from conflict”. In each beer, he claims, two sides of taste — hops and malt — struggle for supremacy. “These two sides wage a war to dominate your palate,” he says, “and the best beers happen when the two sides become entrenched in defensible positions, protracting the battle into epic proportions.”

When I asked why Wohlmut uses the word “quantum”, he explained to me that it was to underscore the “level of seriousness” that he feels ought to be attached to the analysis of beer. Another reason is that, despite his best efforts, he has found it almost impossible to make home-brewed beer consistent in taste and quality – forcing him to conclude that some mysterious, unknown factors in beer production must be operating at the quantum scale.

I am sure that Pais, who liked a good laugh, would drink to that.

Pattern #3: by leaps and Bonds

Another interesting use of the word quantum appears in Ian Fleming’s story Quantum of Solace, which first appeared in Cosmopolitan magazine in 1959 and was reprinted in his collection For Your Eyes Only. It is not a spy thriller, but a serious short story that he wrote while his marriage was failing. The main character, the governor of Nassau, tells Bond late one night in the course of a heart-wrenching story that human relationships can survive even the worst disasters if both partners retain at least a certain amount of humanity. When partners stop caring, and “the quantum of solace stands at zero”, then the pain can not only end the relationship, but also cause the partners to destroy each other.

Fleming’s use of the word “quantum” is close to Planck’s and to the original Latin: it means a finite amount of some quantity. However, the upcoming movie is said to share nothing but the title with the original story, which begs the question: exactly what does the word refer to in the title of the film? I guess we will all have to wait until November when the film is officially released.

The critical point

These are only three of the patterns that Goldhaber and I found. There are others, involving such things as acausality, nonlocality and cats, but there must be more besides. So what manifestations of quantum language have you spotted in popular culture? What patterns do these reveal? And what do these patterns reveal about the social world? Let me know your thoughts and I shall devote a future column to the responses.

What are your favourite examples of quantum, and its affiliated ideas such as complementarity and the uncertainty principle, in popular culture? What patterns do these reveal? E-mail your contributions to rcrease@notes.cc.sunysb.edu.