What would be on Francis Bacon’s list of idols today? Robert P Crease seeks your thoughts and ideas

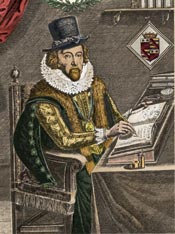

The British scientist and philosopher Francis Bacon (1561–1626) was an avid promoter of science at a time when neither its practice nor its social value was plain. Science and modern life were not yet coupled and Bacon had two problems. One was to teach people how to study the natural world, and the other was to cultivate an appreciation in government circles of why science is useful. Moreover, Bacon had to find ways to be convincing when science was still in an embryonic state, using rhetoric that would persuade his 17th-century contemporaries.

One of Bacon’s most famous rhetorical images – developed in his 1620 treatise Novum Organum Scientiarum, or “New Instrument of Science” – was of the “four idols of the human mind” that hinder our study of nature. Back then, an idol was a powerfully loaded religious term in an era when religious wars were common and witches still persecuted. It meant a false god that distracts us from paying attention to the true god and provides us with reasons why we need not bother.

The human mind, Bacon told his contemporaries, is vulnerable to its own set of idols, which prevent us from seeing nature as it is and tell us that we do not have to. These idols come in four species. “Idols of the tribe” arise from defects in the mind itself, and include the human tendency to see patterns where none exist. “Idols of the cave” are different for each individual, whose background and training inevitably produce biases; some people, for example, overrate parts over wholes, while others wholes over parts. “Idols of the marketplace” stem from language and the way words are often imprecise and misleading. Finally, “idols of the theatre” are systems of thought that are sometimes enlightening but the inner logic of which can also bewitch us and prevent us from seeing the world as it is. (Bacon cited Platonism but we might think of Marxism or Freudianism.) In identifying and exposing these idols, Bacon sought to improve his contemporaries’ ability to practise science and to appreciate its value.

Bacon’s writings seem hopelessly naive today. Bacon had no appreciation for the role of mathematics in science and also wrote as though making discoveries were simply a matter of setting up the right conditions for observing nature. To be fair, Bacon lived in a much different world: when Bacon said “Knowledge is power,” it was at a time when nature was regarded as fearful and threatening, and he was trying to encourage his contemporaries to find out what nature is so they could devise ways of protecting themselves.

Today’s idols

Today we live in the scientifically and technologically rich world that Bacon envisioned, and have a very different perspective. Knowledge can have a dark side too, as we know from any number of examples of our power over nature being misused. We also live in an era when the scientific community is established and thriving. Through education and training, we have ways of addressing the first of Bacon’s problems – namely, instructing people who want to understand nature in how best to avoid the traps and temptations that arise from our own intrinsic, human weaknesses or from our own biases. Scientific language, too, is kept precise, and we have grown sceptical of systems – though, in some physicists’ minds, such complex theoretical packages as string theory can become so bewitching as to make them in effect Baconian idols of the theatre.

Some 400 years after Bacon, however, we still have not solved his second problem: how to cultivate an appreciation for the value of science among government administrators. Solutions to issues involving energy generation, pollution, climate change, food production, population control and health care all require us to apply detailed knowledge of how the world works in its full complexity. We already have much of the necessary science, but it is often blatantly ignored, misapplied or distorted.

Denouncing the rising tide of irrationalism and pseudoscience has not worked. What if we followed Bacon’s lead and sought to educate our peers by identifying and exposing what falsely subverts them from appreciating science? One problem is that these days the word “idol” is popularly used to mean “star” – think of the TV series Pop Idol or American Idol – rather than false god. Another problem is that, while Bacon addressed an educated ruling elite who spoke Latin, today we must address a different and more challenging audience: the ordinary citizens who elect the officials who pass legislation, and who tend to think in media-speak. Still, appealing to the connection of “idol” with “idolatry” – bewitchment – may provide an important rhetorical tool to influence this wider audience.

The critical point

Humans keep inventing new ways to misunderstand nature, and we have to keep inventing new ways to expose these misunderstandings. Our problem is not to couple science and modern life but to stop them decoupling. So what if we compiled a list of modern idols – of the false notions that bewitch us and keep us from looking directly at the world?

One is what I’d call “Idols of the political party”. Human beings worship this idol when they do not consult studies to decide whether, say, climate change is taking place, or evolution is real, or fracking is dangerous – but instead consult the party line of their political or interest group. This party line tells them how to look in the world in the “right” way, and warns them that it is wrong to look at the world differently.

But what do you think are our other modern idols? Send me your thoughts and I shall devote a future column to the responses.