Quantum mechanics, says Robert P Crease, has finally acquired as much cultural influence as Newtonian mechanics, though via a very different path

On the outskirts of Cambridge, next door to the Lyndsey McDermott hair salon on Castle Street, is a pub called the Sir Isaac Newton. Ask those inside why it’s so named and drinkers are likely to stare at you, muttering something about British greatness, history or the small fact that Newton was educated at the university down the road. But the pub’s name reminds us that Newton not only is still a highly influential scientist, but remains a popular icon too. Indeed, his name has also been given to Cambridge University Library’s online course catalogue, to an orbiting X-ray observatory and a unit of force, as well as a computer operating system.

But the use of Newton’s name as a recognizable “brand” is only the most trivial way in which his work has influenced culture. His greatest legacy – Newtonian mechanics – has affected all human life by deepening our knowledge of the world, by expanding our ability to control it, and by reshaping how scientists and non-scientists alike experience it. The arrival of the Newtonian universe was attractive, liberating and even comforting to many of those in the 17th and 18th centuries; its promise was that the world was not the chaotic, confusing and threatening place it seemed to be – ruled by occult powers and full of enigmatic events – but was simple, elegant and intelligible. Newton’s work helped human beings to understand in a new way the basic issues that human beings seek: what they could know, how they should act and what they might hope for.

The Newtonian moment

The Earth and the heavens, according to Newtonian mechanics, were not separate places made of different stuff but part of a “uni-verse” in which space and time – and the laws that govern them – are single, uniform and the same across all scales. This universe is also homogeneous. It is not ruled by ghosts or phantoms that pop up and disappear unpredictably. Everything has a distinct identity and is located at a specific place at a specific time. The Newtonian world is like a cosmic stage or billiard table, where things change only when pushed by forces. All space is alike and continuous, all directions comparable, all events caused.

This picture strongly influenced philosophers, theologians, writers, artists and even political thinkers. Indeed, the philosopher Richard Rorty once referred to “Newtonian political scientist[s]”, who centre social reforms around “what human beings are like – not knowledge of what Greeks or Frenchmen or Chinese are like, but of humanity as such”. Meanwhile, in 2003–2004, the New York Public Library staged an exhibition entitled “The Newtonian Moment” to showcase Newton’s cultural impact and illustrate the revolution in worldview his work brought about. Writing in the exhibition’s catalogue, the historian of science Mordechai Feingold declared that the name was chosen because the Enlightenment and Revolution comprised “the epoch and the manner in which Newtonian thought came to permeate European culture in all its forms”.

Feingold was using the word “moment” in the way historians do, referring to special turning points in which a radically new idea recasts past conflicts and tensions to open up new possibilities for the future. These turning points are cultural paradigm shifts that change what human beings know and do, and how they interpret their experiences. Features of the Newtonian Moment include the assumption of universal continuity, certainty, predictability, sameness across scales, and the ability of scientists to “take themselves out” of measurements to see nature as it is apart from human existence.

The quantum ambush

The Newtonian Moment lasted for some 250 years until the start of the 20th century, when it was ambushed by the quantum. Many scientists initially hoped that they could find a comfortable place for the quantum on the Newtonian stage, but by 1927 it had become clear that the quantum undermined many features of the Newtonian world, raising unprecedented philosophical as well as scientific issues. “Never in the history of science,” wrote the science historian Max Jammer, “has there been a theory which has had such a profound impact on human thinking as quantum mechanics”.

Has the cultural impact of quantum mechanics been simply to supply us with a storehouse of unusual, vivid and sometimes pretentious or even loopy images?

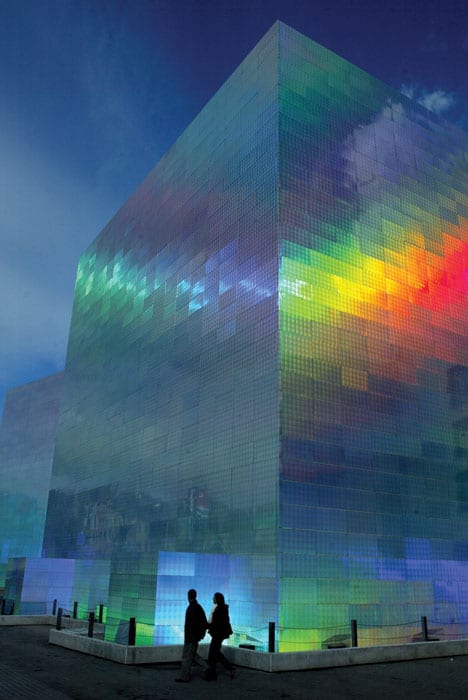

Some scientists tried to explain what was happening by spreading word of quantum physics into ever-widening social spheres that lay beyond science itself. These popularizations encountered an enthusiastic audience. Artists, novelists, poets and journalists were fascinated by the non-Newtonian features of quantum mechanics, including discontinuity, uncertainty, unpredictability, and differences across scales and areas where scientists could not take themselves out of measurements. Quantum terms and concepts – including quantum leap, uncertainty principle, complementarity, Schrödinger’s cat and parallel worlds – eventually appeared in everyday language in sparkling prose and flamboyant metaphors.

But has the cultural impact of quantum mechanics been simply to supply us with a storehouse of unusual, vivid and sometimes pretentious or even loopy images? Or has the cumulative effect been more serious, and reshaped how even non-scientists view the world?

To some extent, the quantum’s impact on artists, writers and philosophers was that it helped free themselves from their own Newtonian-inspired misconceptions. A year or two after the discovery of the uncertainty principle in 1927, for instance, the writer D H Lawrence penned the following poem fragment.

I like relativity and quantum theories

Because I don’t understand them.

And they make me feel as if space shifted About like a swan that can’t settle,

Refusing to sit still and be measured;

And as if the atom were an impulsive thing

Always changing its mind.

Lawrence’s playfully negative remarks may suggest that his attraction is superficial: he likes relativity and quantum theories because they connect better with his experiences of the world as quixotic and immeasurable. A similar sentiment was expressed by the Austrian-Mexican artist Wolfgang Paalen in 1942 when he wrote excitedly that quantum mechanics heralds “a new order in which science will no longer pretend to a truth more absolute than that of poetry”. The outcome, he continued, will be to legitimize the value of the humanities, and “science will understand the value of art as complementary to her own”.

Meanwhile, in 1958 when the New York University philosopher William Barrett reviewed 20th century scientific developments, including quantum mechanics, he concluded that they paint an image of man “that bears a new, stark, more nearly naked, and more questionable aspect”. We have been forced to confront our “solitary and groundless condition” not only through existentialist philosophy but also via science itself, which has triggered “a denudation, a stripping down, of this being who has now to confront himself at the centre of all his horizons”.

Such remarks suggest that humanists embraced quantum mechanics because they experienced the Newtonian universe as a cold and constricting place in which they felt defensive and marginalized – with the news of the strangeness of the quantum domain coming almost as a relief. But if this is the only reason humanists found developments of the quantum world liberating, it was surely their own doing, for they were relying far too seriously on science to begin with in understanding their own experience.

A new humanism

In 1967 the critic and novelist John Updike wrote a brief reflection on the photographs and amateur films taken in Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas on 22 November 1963, in the few momentous seconds when President John F Kennedy’s motorcade drove through and he was hit by an assassin’s bullets. The more closely and carefully the frames were examined, Updike noted, the less sense the things in them made. Who was the “umbrella man” sporting an open umbrella despite it being a sunny day? Who was the “tan-coated man” who first runs away, then is seen in “a gray Rambler driven by a Negro?” What about the blurry figure in the window nextto the one from which the shots were fired? Were these innocent bystanders or part of a conspiracy?

“We wonder,” Updike wrote, “whether a genuine mystery is being concealed here or whether any similar scrutiny of a minute section of time and space would yield similar strangenesses – gaps, inconsistencies, warps and bubbles in the surface of circumstance. Perhaps, as with the elements of matter, investigation passes a threshold of common sense and enters a subatomic realm where laws are mocked, where persons have the life-span of beta particles and the transparency of neutrinos, and where a rough kind of averaging out must substitute for absolute truth.”

Years later, many frames turned out to have rational explanations. The “umbrella man” was identified – to the satisfaction of all but diehard conspiracy theorists. Testifying before a Congressional committee, the man in question said he had been simply protesting against the Kennedy family’s dealings with Hitler’s Germany, with the black umbrella – Neville Chamberlain’s trademark fashion accessory – being a symbol for Nazi appeasers. Far from heralding a breach in the rationality of the world, the umbrella man was just a heckler.

Barrett, being a philosopher, had proposed that the cultural effect of quantum mechanics was to strip us of illusions. Updike, a novelist with a keen interest in science who followed contemporary developments in physics with care, reached a different conclusion. His words above indicate that he saw the impact of quantum mechanics on culture to be deeper and more positive than Barrett had. Indeed, Updike often has his fictional characters refer to physics terms in a metaphorical way that allows them to voice their experiences more articulately.

The novelist was fully aware that when scientists look at the subatomic world frame by frame, so to speak, what they find is discontinuous and strange – its happenings random except when collectively considered. Updike also knew that most of us tend to find our lives following a similar crazy logic. Our world does not always feel smooth, continuous, reliable, law-governed, stable and substantive; close up, its palpable sensuousness is often jittery, discontinuous, chaotic, irrational, unstable and ephemeral. Reality today does not seem to have the gentle, universal continuities of the Newtonian world, but is more like that of the surface of a boiling pot of water. Using quantum language to describe everyday conditions may therefore be technically incorrect but is metaphorically apt.

In another essay, Updike wrote that “our century’s revelations of unthinkable largeness and unimaginable smallness, of abysmal stretches of geological time when we were nothing, of supernumerary galaxies and indeterminate subatomic behaviour, of a kind of mad mathematical violence at the heart of matter have scorched us deeper than we know”. The scorching brought about by such scientific discoveries, Updike proposed, had given birth to a “new humanism” whose “feeble, hopeless voice” is provided by the “minimal monologuists” of the Irish playwright Samuel Beckett – and which is also evident in the instantly recognizable “wire-thin, eroded figures” of the Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti.

The critical point

If only all human voices were as articulate as Beckett and Giacometti! Too frequently, the use of quantum language and concepts in popular culture amounts to what the physicist John Polkinghorne calls “quantum hype”, or the invocation of quantum mechanics as “sufficient licence for lazy indulgence in playing with paradox in other disciplines”. This is how it principally appears in things like TV programmes, cartoons, T-shirts and coffee cups.

Updike’s remarks, however, suggest that quantum mechanics – a theory of awesome comprehensiveness that has yet to make an unconfirmed prediction – has done more than help to deepen our knowledge of the world and to expand our ability to manipulate it. The novelist’s remarks suggest that quantum mechanics – though a modification, not a replacement, of Newtonian mechanics – has provided us with a range of novel and helpful images to interpret our experiences of the world in a new way, on a scale equal to or possibly even greater than Newtonian mechanics. Quantum physics is metaphorically appealing because it reflects the difficulty we face in describing our own experiences; quantum mechanics is strange and so are we.

Someday, indeed, the era after the Newtonian Moment may come to be known as the Quantum Moment.