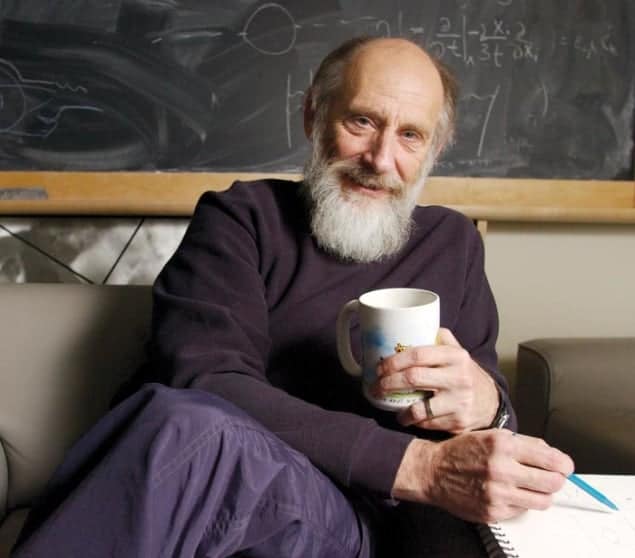

Lowry Kirkby reviews The Theoretical Minimum: What You Need to Know to Start Doing Physics by Leonard Susskind and George Hrabovsky

The mantra for popular-science books is to minimize the use of equations. In The Theoretical Minimum: What You Need to Know to Start Doing Physics, authors Leonard Susskind and George Hrabovsky have taken the opposite approach by producing a physics book for the educated general public that emphasizes the mathematics needed to solve physics problems.

When I first heard about the premise of the book, I was intrigued. Is there a group of people who want to solve physics and mathematics problems, and not simply read about the gee-whiz physics that is the standard fare of most popular-science books? To my surprise, apparently there is. The Theoretical Minimum is the product of a series of lectures that Susskind presented for the general public in the Stanford area – all of which can be found video-recorded on the Web – and these lectures attracted a large following of people who were, in Susskind’s words “hungry to learn physics”. Indeed, Hrabovsky himself was one of those people. Now president of the Madison Area Science and Technology organization, which is devoted to research and education, Hrabovsky has no formal scientific training but taught himself physics and mathematics – presumably through courses and books similar to The Theoretical Minimum.

This thirst for academic learning outside of a conventional university degree reminded me of the recent and rapid growth of so-called massive open online courses, or MOOCs: open-access (i.e. free) university courses that give people of any age or background the chance to learn about a subject that interests them, at their own pace (see p9 of the print edition). Like MOOCs, The Theoretical Minimum allows knowledge-lovers to get their teeth into the kind of physics and mathematics problems that one would normally face during a university degree. As Susskind puts it, it is intended for “people who once wanted to study physics, but life got in the way”.

The book is written in the form of 11 short lectures that cover classical mechanics, plus a final chapter on electromagnetism. Though replete with equations, it remains very readable. Abstract concepts are well explained, usually in a couple of different ways to give the reader a good conceptual overview of the principle at hand. For example, one does not need to understand every detail of a given equation in order to comprehend its power and its use, since these are explained in the text. In addition, each lecture includes several exercises, allowing readers to put their problem-solving skills into practice. (Solutions to the exercises are posted on the Web.) The first three chapters include mathematical interludes on trigonometry, vector notation, differentiation and integration. These discussions are complete, and would serve as a good reminder for someone who is already familiar with calculus; however, they are also rather terse, and would likely be too advanced for someone who wishes to learn it for the first time.

I found it satisfying to finally gain a basic understanding of Lagrangian and Hamiltonian mechanics

Is this really just the minimum you need to know to start doing physics? To me, the answer is an emphatic “no”: this book covers far more than the minimum. The first five chapters cover the core classical mechanics principles of motion and dynamics, including conservation of energy and momentum, while the material covered in the second half of the book (chapters 6–12) is usually considered “advanced classical mechanics”. This material – which includes Lagrangian and Hamiltonian mechanics and their applications to electric and magnetic forces – is often not taught at undergraduate level in the UK since it is not part of the Core of Physics syllabus issued by the Institute of Physics. Indeed, I did not cover these subjects during my undergraduate physics degree at the University of Oxford. As such, I can attest to the readability of the book: I was able to understand what an equation that I had never seen before represents, without having to pick apart and understand every term that makes it up. In fact, I found it satisfying to finally gain a basic understanding of Lagrangian and Hamiltonian mechanics, since I had sometimes wished we had covered these subjects in my degree. I even felt like I had been partially duped during my degree after reading Susskind’s comment that the Euler–Lagrange equations comprise “all of classical physics in a nutshell”!

There is, however, a flip side to my satisfaction at filling in some holes left by my undergraduate degree: I found myself wondering how much someone who has not had formal mathematics or physics training would really get out of The Theoretical Minimum. The concepts presented in it are not only advanced, but also abstract and unintuitive, and I would imagine they would be quite daunting to someone new to the subject. At the very least, they would leave newcomers scratching their heads. The book is really about explaining mathematics and abstract physics and does very little to relate these concepts back to everyday life. In addition, in many instances I thought that the explanation would benefit from a diagram or two. Susskind is one of the fathers of string theory, arguably one of the most abstract and theoretical areas of physics. However, the rest of us are not: we need a more tangible way to learn.

In summary, although this book probably offers more than many readers will have bargained for, it does provide a clear description of advanced classical physics concepts, and gives readers who want a challenge the opportunity to exercise their brain in new ways. Thanks to the breadth of accompanying information (for example, exercises and video-recorded lectures on the Web), it also enables them to learn at their own pace, and hopefully most will get some fun and satisfaction from it. If members of the general public really are pulling for these types of courses, ones that offer rigour and a challenge, I enthusiastically encourage them.

- 2013 Basic Books £20.00/$26.99hb 256pp