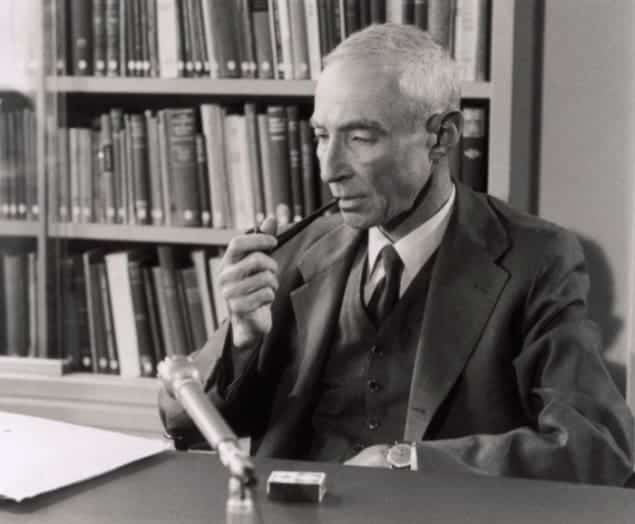

Robert P Crease reviews Robert Oppenheimer: a Life Inside the Center by Ray Monk

J Robert Oppenheimer has proven all but unfathomable to his biographers. It is not easy to craft a convincing portrait of someone who was alternately brilliant and obtuse, eloquent and shallow, arrogant and insecure, robust and fragile. Handsome and charismatic, the head of the Manhattan Project to build the atomic bomb cultivated friends in high places, but he could also be callous and even vicious toward friends and intimates. The range of reactions he inspired is as discordant as his character. Some people called him a secular saint, a “Gandhi stretched up to six feet”, while others saw him as treacherous – a brutal, petty and often pretentious colleague.

Moreover, Oppenheimer was notoriously guarded. He left no personal diary, no autobiography. He repeatedly and deliberately frustrated efforts by interviewers to elicit personal feeling and reflections. A biographer has little to go on in figuring out what drove this driven man, despite the existence of years of now-public wiretaps and FBI surveillance. As Ray Monk puts it in his masterful new book Robert Oppenheimer: a Life Inside the Center, “Not revealing things about himself was something he was extraordinarily good at.”

Monk is hardly the first scholar to try his hand at explaining one of the 20th century’s most enigmatic scientists. Indeed, several biographies appeared around 2005 in the wake of the centennial of Oppenheimer’s birth. These include the Pulitzer-prizewinning American Prometheus (2005) by Kai Bird and Martin J Sherwin; and Abraham Pais’s J Robert Oppenheimer: a Life (2006), to which I contributed after Pais died with the manuscript unfinished. Yet all of these biographies managed to paint their respective portraits by adopting partial perspectives, whether historical, sociological or political.

Monk’s biography improves on them by subtly shifting the focus away from the man to his interactions with his surroundings. It presents Oppenheimer as a man consumed by centres – social, scientific, political. Monk describes the dynamics of Oppenheimer’s life as efforts to move towards these centres, to maintain his unstable presence at them and to avoid falling away from them. In part one, for instance, Monk goes to some lengths to describe the German Jewish community on Manhattan’s Upper West Side in which Oppenheimer was born and raised in the early 1900s. This community was struggling to fit in not only with its adopted country but also with more recent Polish and Russian Jewish immigrants who landed in the “Jewish Ghetto” on the city’s Lower East Side. Monk describes the leaders of this centre-aspiring community and its institutions, including the Ethical Culture School, which Oppenheimer attended. He presents Oppenheimer as a youth whose German and Jewish background propelled him to seek to become a devoted American, and whose patriotism and assimilation into American life were unequivocal.

Monk also dwells on Oppenheimer’s intense and formative personal relationships with classmates and teachers en route to his becoming a promising young theorist, one who managed to show up at the centre of theoretical physics (Göttingen) at a time (1926) of radical change: the quantum revolution. Yet for Oppenheimer, it was not enough merely to be at the centre of theoretical physics. He wanted that centre to be American, and after leaving Europe, he quickly set out to build the US’s first school of theoretical physics.

In succeeding chapters, Monk portrays other kinds of centre-seeking movements, as Oppenheimer became the surprise choice to lead one of the riskiest military ventures ever, the Manhattan Project, and as he afterwards sought to play a key role in shaping US atomic policy, only to be expelled after a gruelling and humiliating series of security hearings. Monk enables us to understand why Oppenheimer was so determined to brave that ordeal, defending himself against charges of disloyalty, when he might have gracefully stepped back.

Strangely, Monk does not go into as much detail about Oppenheimer’s later personal relationships as he does with his earlier ones. A lack of evidence may be partly to blame; Oppenheimer’s wife and children, in particular, seem to have shared his reticence about putting personal feelings on paper. Even so, plenty of people knew his late wife and daughter, and his son is still alive, though elusive. Some sense could have been made of it.

Monk’s care not to overstep the available evidence does pay off later in his treatment of Oppenheimer’s possible Communist Party membership. “The question of whether Oppenheimer was a communist or not is thus rather like the question of whether he was or was not a German Jew,” Monk writes insightfully. “He did not consider himself to be German, Jewish or communist and yet, as those words are commonly used, he was ethnically a German Jew and politically a communist. One does not have to accuse either Oppenheimer or common usage of being wrong here; one just has to be careful in distinguishing the sense in which he was and was not German or Jewish or a communist.”

Only occasionally does Monk falls prey to Oppenheimer-mystique: the temptation to read deep meanings into the man’s verbiage when more mundane explanations are likely. When Oppenheimer named a used car “Ichabod”, Monk proposes that he was thinking of an obscure Old Testament priest – the son of Phinehas in the Book of Samuel – or a figure in an enigmatic Robert Browning poem. Oh, come on. The car’s most probably named after Ichabod Crane, the itinerant schoolteacher famously chased by a headless horseman in Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow – a tale known to every New York schoolchild.

Unlike most other biographers, Monk takes Oppenheimer’s scientific concerns seriously. Quantum electrodynamics, he notes, had an “extraordinary hold” on Oppenheimer in the 1930s, and he quotes a student’s recollection about Oppenheimer’s determination to make sense of the meson puzzle: “it bothered him, it tore at him”. In her New York Times review of this book, the journalist Janet Maslin chides Monk for wasting so many pages on things like mesons, asking sarcastically: “Would anyone seriously interested in Oppenheimer seek out a biography for this?” Gosh, how small-minded! But Monk appreciates just how captivating science is to the true scientist. “I need physics more than friends,” he cites Oppenheimer as saying.

Isidor Isaac Rabi once said that, while most physicists regard physics as simply a profession, Oppenheimer regarded it as a path to deeper truths; physics for Oppenheimer was therefore a means to the Centre. The towering achievement of Monk’s book is that it finally makes this plausible. J Robert Oppenheimer has never made more sense.

- 2013 Doubleday/2012 Jonathan Cape $37.50/£30.00hb 832pp