Kate Brown reviews The Girls of Atomic City: the Untold Story of the Women Who Helped Win World War II by Denise Kiernan

Denise Kiernan’s The Girls of Atomic City tells the story of a dozen women who left rural America in the early 1940s and tumbled suddenly, like Alice down the rabbit hole, into the nascent US military-industrial complex, with all its regulations, factory discipline, dangers and surveillance. These women, along with thousands of others like them, made up the major part of the labour force of the factory in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, that enriched uranium for the Manhattan Project’s first atomic bomb. Kiernan narrates the story from the perspective of these ill-informed young women, who worked in blackout security conditions with no information about what they were doing, or why.

In this accessible account, each woman’s story, derived from Kiernan’s oral interviews, is spliced together with that of the others. To provide some of the background that “the girls” themselves lacked at the time, Kiernan intersperses their personal stories with chapters on “tubealloy” – the code name for uranium. These chapters give the standard account of the Manhattan Project, featuring the big men whom Kiernan refers to as “The General” (Leslie Groves), “The Scientist” (J Robert Oppenheimer) and “The Engineer” (Kenneth Nichols). For this master narrative, Kiernan draws on a couple of dozen archival documents, and relies heavily on the book City Behind a Fence by Charles Johnson and Charles Jackson, along with Peter Bacon Hales’ masterful Atomic Spaces.

The tales of “the girls” frequently stress their naivety, ignorance and fear of security officials. However, in writing about them, Kiernan focuses on conventional “women’s issues” to the point where, at times, the prose descends to the mundane. For example, when Celia Szapka and a few of her fellow northerners stopped at a café near the end of their journey to Oak Ridge, Kiernan writes, “One menu item puzzled them…None had heard of any such thing as ‘grits’.” Kiernan explains that Szapka’s Polish mother had cooked mostly potatoes, rather than the cornmeal porridge that was (and is) a staple of southern American food.

Celia liked the grits, and in the book they form part of her “arrival” story – one of many stories in the book to contain first impressions of Oak Ridge. This muddy town of hutments, prefab housing and corrugated steel structures took shape quickly, accommodating 75,000 new residents in just a few months, but in Kiernan’s account, the reader learns less about the effects of placing a dangerous plant in the middle of a rural community or about the women’s work, and much more about their food, dating, wardrobe, weddings and families. The Girls of Atomic City, as a consequence, reads like Physics World welded to Good Housekeeping.

This is a shame because Kiernan provides some fascinating material that adds to the history of the Manhattan Project. Rosemary Maiers, who had worked as a nurse at Oak Ridge’s first medical clinic, related to Kiernan the story of a young naval ensign who suffered a nervous breakdown at the plant and started to do exactly what was forbidden: he talked, babbling on and on about the secret plant and the weapons it was going to produce. Afraid to release the voluble young man to medical care away from the nuclear reservation, the site psychiatrist Eric Clarke commandeered an apartment and locked the sailor in, treating him with electric shock therapy.

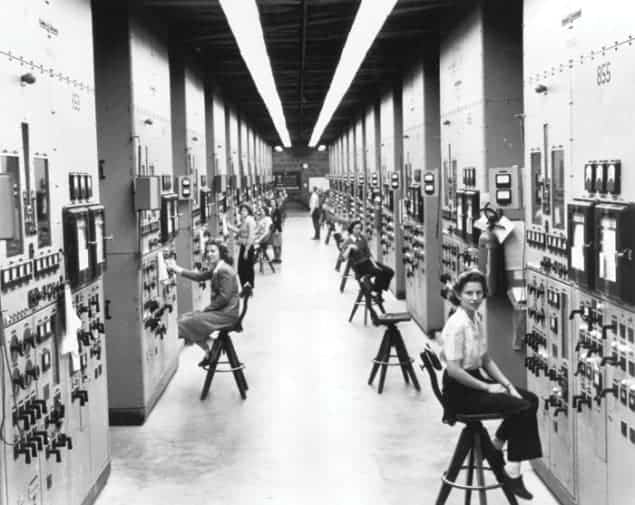

Kiernan also recounts how some women, just out of high school, operated the plant’s array of “calutrons” – the large electromagnetic separators built to disentangle U-238 from U-235. The women challenged the male scientists at Ernest Lawrence’s lab in Berkeley, California, where the calutron was invented, to a race to see who could generate more “product” (enriched uranium) per run. The “girls” handily beat the California PhDs. Lawrence explained his team’s loss with condescension, rationalizing that his crew was always fiddling with the dials trying to make the calutrons run faster and smoother, while the girls stayed on task precisely following directions. Kiernan doesn’t question why, then, the PhDs, with all their extra knowledge and expertise, didn’t in fact succeed in producing more enriched uranium, more quickly.

Later in the book, Kiernan provides intriguing new material on the story of Ebb Cade, a black employee who, after landing in the Oak Ridge hospital following a car crash, was deployed as a human lab rat. Expecting that Cade would soon die of his injuries, Manhattan Project doctors injected a sizable dose of plutonium into his veins to see how much lodged in his body. For this part of her story, Kiernan quotes from an oral history by Karl Morgan, a health physicist. Morgan described how Robert Stone, one of the leading lights of the Manhattan Project medical programme, told him about the opportunity the badly injured Cade presented when he was checked into the hospital: “Karl, do you remember that [racial epithet] truck driver that had this accident some time ago?” Stone then laid out how they planned to take samples of bone, liver and other organs from Cade’s body after his death.

When Cade refused to expire, Stone and the other doctors nevertheless held off setting his broken bones for 90 days in order to let the plutonium travel through his body before taking bone samples during surgery. As another consolation prize, they extracted 15 teeth, which they determined Cade no longer needed, as sample material. Kiernan recounts how in Morgan’s version, Cade, clearly suspicious of his “treatment” at the hospital, ran away as soon as he was ambulatory, taking with him his valuable plutonium-laced urine, faeces and organs. Unfortunately, much of the incriminating material of this story is buried in the endnotes. More distressing, Kiernan describes the event and lets it lie, undigested, for her readers to figure out just what this episode means to her larger history.

So what is the message of The Girls of the Atomic City? Kiernan doesn’t directly state it, but she implies that she is adding to the trope of the “greatest generation” – the journalist Tom Brokaw’s description of the Americans who grew up with the deprivations of the Great Depression and made a decisive contribution to the war effort. Kiernan is right to suggest that women, too, numbered among the Americans who worked, sacrificed and soldiered on selflessly for a just cause, although she is by no means the first to do so. But in seeking to balance between “commemoration and celebration”, Kiernan draws back from assessing the impact of this pioneering nuclear-weapons community on democracy, civil rights and public health. While she sporadically acknowledges that there were problems – including the loss of civil rights, incessant surveillance, segregation, gender and racial discrimination, medical experimentation on unwitting human subjects and (though Kiernan does not address it) residents being unknowingly subjected to toxic and radioactive contaminants – her narrative choices unfortunately lead the reader to feel a lot like Alice, lost in a historical Wonderland with little direction or analysis.

- 2013 Touchstone Books £16.67/ $27.00hb 373pp