Basil Mahon reviews James Watt: Making the World Anew by Ben Russell

Like the legend of Isaac Newton seeing an apple fall, the story of young James Watt carefully observing steam coming from a tea kettle has become part of British folklore. A popular painting shows him being watched by an aunt, whose puzzled and disapproving expression holds dramatic irony: unlike us, she doesn’t know that her nephew would go on to invent the modern steam engine and so change the world.

The title notwithstanding, Ben Russell’s main theme in James Watt: Making the World Anew is not Watt the man. Rather, he uses Watt as a “lens” through which to examine how the process of “making things” evolved during the industrial revolution. He does, indeed, guide us through the varied phases of Watt’s long and productive life, but also invites us to study a somewhat neglected aspect of the industrial revolution: the part played by craftsmen such as clockmakers, instrument makers, potters, blacksmiths and millwrights. As Russell points out, without the people who actually made things, the ideas that inspired progress would have remained just ideas.

Watt himself was both a thinker and a doer. His most famous invention – the steam engine with a separate condenser – drew on both attributes and demonstrates his ability to go on thinking (and doing) long after most people would have given up. He realized that contemporary engines wasted a great deal of heat every time water was injected into the cylinder to condense the steam, and began to experiment with ways to reduce the waste, using his skill as an instrument maker in improvising apparatus for the purpose. He found that the problem was not caused by heat escaping through the cylinder walls, as he had first thought, but by the cast-iron cylinder cooling and having to be reheated at every stroke. The solution was to send the steam to a separate vessel to be condensed; then the cylinder would remain hot and the condenser could be kept cool, thus wasting far less heat. So stated, it sounds simple, but the idea came to Watt only after he had gained understanding of the properties of steam – specific heat, latent heat and elasticity – through his experiments and his discussions with the natural philosopher, Joseph Black.

Although trained as a maker of scientific instruments, Watt turned his hand to all manner of crafts wherever he saw potential markets. Despite being tone-deaf, he made and sold flutes and guitars. No-one matched Watt’s almost superhuman versatility but, as Russell points out, ambitious craftsmen everywhere were developing new techniques and identifying new materials – anything that could give them an edge over their competitors. In doing so, they improved existing products and found ways to make new ones. Some, notably Josiah Wedgwood, were able to anticipate the needs of society in a spectacularly successful way. Others fell prey to the whims of fashion. When, in the late 1700s, people abandoned fancy shoe buckles in favour of cheaper and more practical shoelaces, 20,000 buckle-makers petitioned the Prince of Wales, and the Birmingham Gazette ran a despairing article in May 1790 contrasting the “manly buckle” with “that most ridiculous of all ridiculous fashions, the effeminate shoestring”.

An important part of the ambitious craftsman’s business was to deal with people – to negotiate contracts, chase slow payers and discipline recalcitrant workers. Though far from shy when in congenial company, Watt hated this rough stuff. He was, however, keen to strike good bargains and to secure his legal ownership of inventions, and was lucky to find a partner, the manufacturer Matthew Boulton, who was a master of such arts. It was Boulton who persuaded Watt to patent the principles of his separate condenser rather than the means of applying them. This patent eventually made Watt a very rich man, but only after he and Boulton had pursued many people who had infringed the patent or withheld royalty payments, and, in the end, got a significant proportion of them to pay.

Anyone who opens this book expecting to read a story is likely to be disappointed. Russell gives us instead a course of lectures, meaty ones, that draw on a great many sources. (He lists 787 references.) The text is copiously illustrated but is not all easy going, and at times one may wish for some smooth paraphrasing rather than clunky quotes from original letters and papers. It’s good, authentic stuff though, and we learn some surprising facts (surprising to me, at least). For example, waterwheels persisted far longer during the industrial revolution than I had thought. Moreover, they were sometimes used together with steam engines in a hybrid arrangement, rather like that in today’s petrol/electric cars. In some installations the steam engine would be brought in only when the water supply failed; in others the steam engine actually fed water to the water wheel.

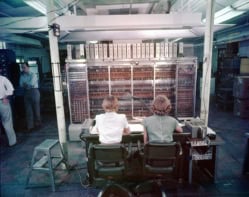

Perhaps from a wish to emphasize the importance of craft work in the industrial revolution (as a companion to the importance of science which has already been much written about), Russell has made a strange omission. He tells us nothing about Birmingham’s Lunar Society, of which Watt and Boulton were leading members along with Joseph Priestley, Erasmus Darwin and Josiah Wedgwood. (The society was an informal group that met monthly around the time of the full moon for dinner, gossip, and scientific talk. Its members strongly supported each other and, together, wielded great influence.) The omission is especially odd as Russell has included an illustration of society members sitting round a table drinking coffee.

James Watt epitomises the fusion of craft with science that brought about the industrial revolution and created the profession of engineering. Anyone with more than a passing interest in the comparatively neglected role of craft in this process will find this book good value.

- 2014 Reaktion Books £17.95/$29.95hb 256pp