A new gel made by combining molecules routinely employed in chemotherapy and immunotherapy could help treat aggressive brain tumours known as glioblastomas, according to new work by researchers at Johns Hopkins University in the US. The gel can reach areas that surgery might miss and it also appears to trigger an immune response that could help suppress the formation of a future tumour.

Glioblastomas are the most common, and most dangerous, type of brain tumour. Conventional treatment typically involves a combination of surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy, but patient outcomes are generally poor.

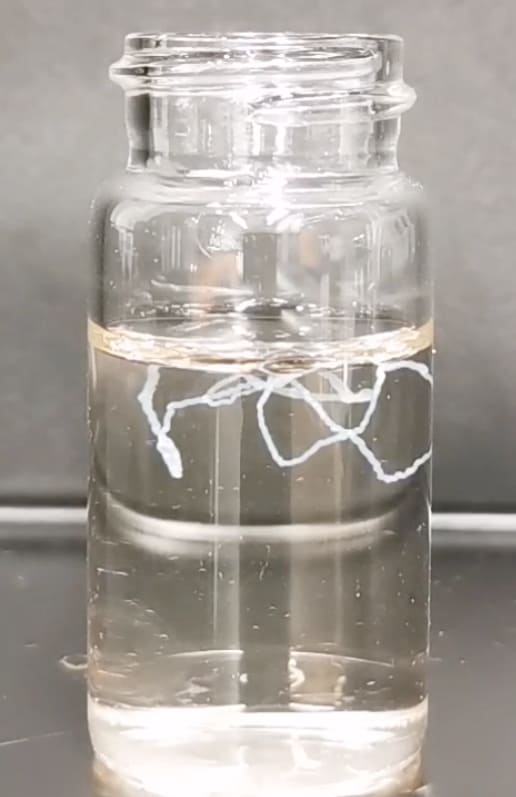

In the new work, the researchers, led by bioengineer Honggang Cui, made their gel by converting the small-molecule, water-insoluble anticancer drug paclitaxel into a molecular hydrogelator. They then added aCD47, a hydrophilic macromolecular antibody, in solution to this hydrogelator. To be able to do this, the researchers first used a special chemical design to assemble the paclitaxel into filamentous nanostructures.

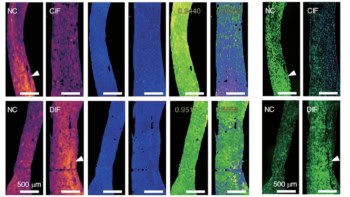

When loaded into the resection cavity left behind after a tumour has been surgically removed, the mixture spontaneously forms into a gel and seamlessly fills the minuscule grooves in the cavity, covering its entire uneven surface. The gel can reach areas that may have been missed during surgery and that current anticancer drugs struggle to reach. The result: lingering cancer cells are killed and tumour growth suppressed, say the researchers. They describe their technique, which they tested in mice, in PNAS.

The gel releases the paclitaxel over a period of several weeks. During this time, the gel remains close to the injection site, reducing any “off-target” side effects. It also appears to trigger a macrophage-mediated immune response that sensitizes the tumour to the “don’t eat me” signal induced by the aCD47.This, in turn, promotes tumour cell phagocytosis (one of the main methods by which cells, particularly white blood cells, defend our body from external invaders) by immunity-promoting macrophages and also triggers an antitumour T cell response. In this way, the aCD47/paclitaxel filament hydrogel effectively suppresses the recurrence of a future brain tumour.

Ultrasound-powered implant treats brain cancer using electromagnetic fields

In tests on mice with brain tumours, the gel prolonged the overall survival rate of animals that hadn’t undergone tumour surgery to 50%. This figure increased to a striking 100% survival in mice that also had surgical removal of the tumour.

“The gel could supplement the current and only FDA-approved local treatment for brain tumours, the Gliadel wafer,” Cui tells Physics World. “The current formulation also has the potential to treat other types of human cancer.”

The Johns Hopkins team now plans to test its gel in other animals to further confirm its therapeutic efficacy. “We also plan to undertake more studies to assess its potential toxicity and determine dose regimens,” says Cui.