This summer, the theoretical physicist Robert Oppenheimer captured widespread public fascination thanks to the film Oppenheimer. The unlikely blockbuster details the life of Oppenheimer as he led the development of the atomic bomb and the conflict he couldn’t escape after it was dropped.

Tomorrow, the winner(s) of the 2023 Nobel Prize for Physics will be announced and that has led me to wonder why Oppenheimer never won a prize (he was nominated three times). Indeed, a further review of the Nobel prize archives reveals an even more puzzling question: why has there never been a physics Nobel given for the discovery of nuclear fission? Surely, the discovery of such a phenomenon warrants this recognition.

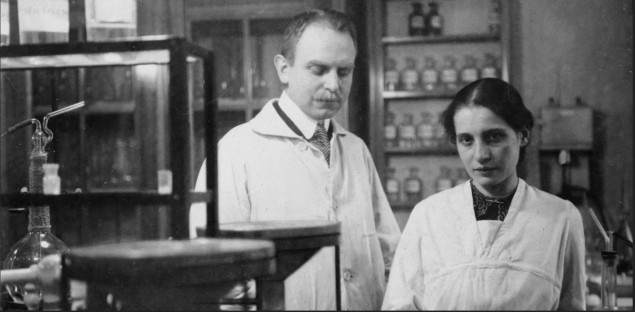

The answer lies in the stories of Otto Hahn and Lise Meitner, a German radiochemist and Austrian–Swedish nuclear physicist, respectively, who lived and worked through the rise of Nazism and the Second World War.

Complementary colleagues

The pair worked closely throughout the first decades of the 20th century, isolating and studying radioactive nuclei. Their complementary working relationship shone in the years following Enrico Fermi’s discovery in 1934 that neutron bombardment could be used to transform one element into another – work that earned Fermi the 1938 physics Nobel.

However, in 1938 Meitner – an ethnically Jewish woman – was forced to flee Nazi Germany and escaped to Sweden. There she worked at a facility that had just been set up by the physics Nobel laureate Manne Siegbahn. Meitner did not have funding to do research in wartime Sweden and some scholars suggest that her presence was resented by Siegbahn, and that he attempted to block her professional career in Sweden.

Meanwhile in Germany, Hahn continued his work along with a new assistant Fritz Strassman. During that year, Hahn and Strassman consulted Meitner on the puzzling products of the neutron bombardment of uranium, which resulted in an element too light to be the product of any known radioactive decay process. Stories say that on Christmas Eve 1938, Meitner and her nephew Otto Frisch (who would later work on the Manhattan Project with Oppenheimer) concluded that the uranium atom had been split.

Distinct papers

Hahn and Strassman published their experimental findings in the journal Naturwissenschaften in January the next year. Meitner and Frisch published their theoretical interpretation of these findings separately in Nature just a couple weeks later. These papers were distinct to their disciplines: chemistry and physics respectively.

In this situation, who would you say discovered nuclear fission – the people who performed the experiment or the people who interpreted its results? Some scholars suggest that Hahn was keen to frame the discovery of nuclear fission as a chemical discovery, not a physical one. Perhaps this was out of self-preservation, as collaboration with a Jewish woman would have ruined Hahn’s career in Nazi Germany. Fission might protect Hahn and his laboratory during those tumultuous times.

In 1944 it was announced that the Nobel Prize for Chemistry would be awarded to Hahn for the discovery of nuclear fission and no-one else, notably excluding Meitner, Strassman and Frisch. Prominent physicists, including Niels Bohr, Max Planck and Arthur Compton, protested Meitner’s exclusion and nominated her for the physics prize in the years that followed but to no avail.

German hyperinflation, and what it has to do with a Nobel prize

So why was there no Nobel Prize for Physics awarded for fission in the subsequent years? In the case of Meitner, some scholars suggest that Siegbahn’s animosity prevented her from winning. As a leading Swedish physicist, he would have held considerable sway over who was given the prize.

And then there are the atomic bombs that were dropped on Japan in 1945, killing as many as 226,000 people. Both of these devices relied on nuclear fission, which was seen in an increasingly negative light as the threat of all-out nuclear war became real in 1949, when the Soviet Union tested it first bomb.

In the 1950s several German nuclear scientists, including Hahn, signed the Gottingen Manifesto declaring they would not participate in arming West Germany with nuclear weapons. They were ready to move past the subject, and perhaps the Nobel committee was ready to do the same.

Physics World‘s Nobel prize coverage is supported by Oxford Instruments Nanoscience, a leading supplier of research tools for the development of quantum technologies, advanced materials and nanoscale devices. Visit nanoscience.oxinst.com to find out more.