Jemima Coleman and Wendy Sadler say that science magazines have a responsibility to ensure that science is accessible and inclusive for all

Magazines have been an effective method of communication since their introduction in the 17th century. They now encompass an endless variety of topics and disciplines from pigs and cranes to trains and, of course, science. Science magazines are an integral part of science communication to the public, with popular-science magazines drawing reader figures above the hundreds of thousands per year across both digital and physical issues.

Digital magazines are becoming increasingly popular and can help make magazines more accessible such as the text being read aloud to readers or having it enlarged for people with visual impairment. However, that accessibility doesn’t necessarily lead to inclusivity, with research showing that science magazines are read mostly by male readers. This is in line with the wider gender gap in science, which sees men being invited to submit papers at twice the rate of women and male-authored papers having a higher impact factor than papers authored by their female colleagues.

Deciding to buy a magazine as a one-off purchase is a complex psychological process that is not well understood but involves readers judging the cover by its image choice, layout, topic, colour and visibility. We explored what could influence this process by analysing the digital readership databases for over 100 covers of the astronomy magazine All About Space, which is published by Future Plc and aimed at non-scientist lay readers. Future gave us access to the magazine’s online database, which included information such as the gender of readership (provided by readers when they subscribe).

In terms of the number of people who open a digital copy of All About Space on the website, the magazine has a digital readership of about 1100 people per month, with an average female readership of 11.1%. We then examined how readership is affected by the themes that appear on the magazine’s cover.

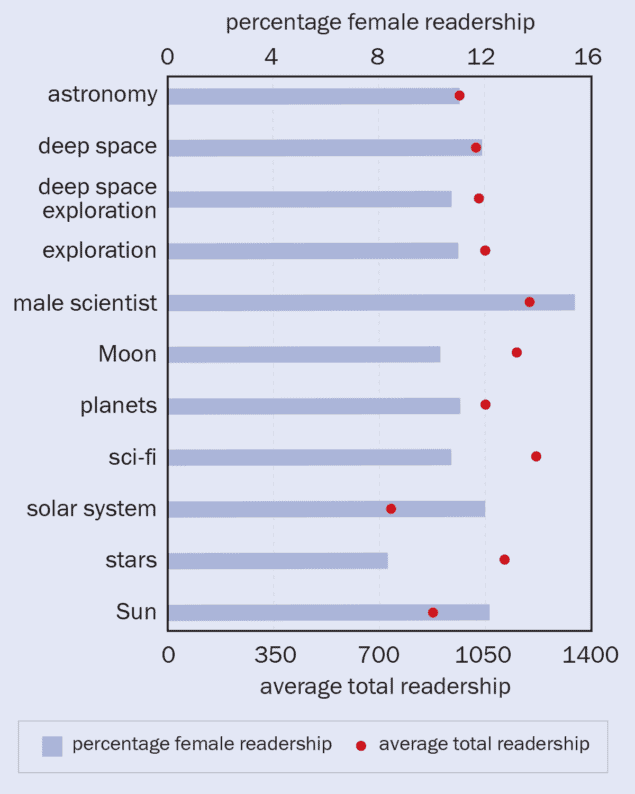

Research suggests that having a question on the front cover can draw people in to find out more and we found that this is the case with overall readership increasing by 13%, on average, while having the theme of ‘”sci-fi” on the cover or in the title also resulted in a higher-than-average overall readership with an average of 1268 readers (see below image for all subject themes that we examined). Neither of these factors, however, increased the proportion of female readers.

One theme that did impact the number of women readers was, somewhat surprisingly, having a main theme of “stars” on the cover, which resulted in a lower-than-average percentage female readership at just 8.8% (and the lowest total reader number). So what did boost the average number of female readers? Research suggests that people tend to select role models of the same gender so one might think that having an image of a woman somewhere on the cover would boost the proportion of women readers. Yet while a woman on the cover increased overall readership by 9.6%, on average, it didn’t do much to encourage proportionally more women to read the magazine. We suspect that potential readers are not necessarily seeing the smaller images of people on the cover as role models.

When a male scientist or person was the subject of the cover feature, however, we saw the highest overall percentage female readership, with an average of 15.9%. This theme was also one of the most popular overall, with an average of 1213 readers. Of the 100 or so covers studied, there were no examples where a woman was the main subject of the cover, which is disappointing. It’s therefore hard to say if the popularity of the male scientist theme is gender-specific, or due to the inclusion of any person-focused content, or because the featured men were simply well-known celebrity scientists such as Brian Cox or Dara Ó Briain.

Yet this lack of female science celebrity points to a wider systemic cultural issue.

Effective science communication depends on considering the audience being communicated with, including how minoritized communities are represented and supported. As scientists, we want to be inclusive in how we communicate with the whole community, including newcomers or those who are still finding their place in science. We hope that magazine publishers feel a responsibility to ensure the accessibility and inclusivity of science to people of all ages, both in and out of the community. Understanding how to increase magazine readership includes trying to appeal to new audiences without losing existing ones.

Magazines should be aware of readership biases and make conscious and intentional choices about the people featured on the cover to challenge these biases. Including more non-stereotypical images and inclusive content would help attract a diverse readership and in turn help to diversify science more generally. After several decades of marginalized groups such as women, people of colour, disabled people and queer communities being systematically excluded from physics, they deserve content that is made for them and about them.