A new protocol for cloud-computing-based information storage that could combine quantum-level security with better data-storage efficiency has been proposed and demonstrated by researchers in China. The researchers claim the work, which combines existing techniques known as quantum key distribution (QKD) and Shamir’s secret sharing, could protect sensitive data such as patients’ genetic information in the cloud. Some independent experts, however, are sceptical that it constitutes a genuine advance in information security.

The main idea behind QKD is to encrypt data using quantum states that cannot be measured without destroying them, and then send the data through existing fibre-optic networks within and between major metropolitan areas. In principle, such schemes make information transmission absolutely secure, but on their own, they only allow for user-to-user communication, not data storage on remote servers.

Shamir’s secret sharing, meanwhile, is an algorithm developed by the Israeli scientist Adi Shamir in 1979 that can encrypt information with near-perfect security. In the algorithm, an encrypted secret is dispersed between multiple parties. As long as a specific fraction of these parties remain uncompromised, each party can reconstruct absolutely nothing about the secret.

Secure and efficient cloud storage

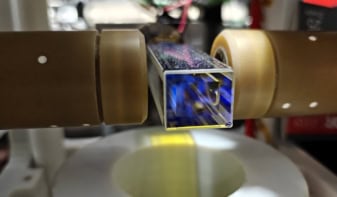

Dong-Dong Li and colleagues at the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) in Hefei and the spinout company QuantumCTek have combined these two technologies into a protocol that utilizes Shamir’s secret sharing to encrypt data stored in the cloud and resists outside intruders. Before uploading data to the central server, an operator uses a quantum random number generator to generate two bitstreams called K and R. The operator uses K to encrypt the data and then deletes it. R serves as an “authentication” key: after encrypting the data, the user inserts a proportion of bitstream R into the ciphertext and uploads it to a central server, retaining the remainder locally. The proportion the user uploads must be below the Shamir threshold.

In the next step, the central server performs what’s known as erasure coding on the ciphertext. This divides the data into packets sent on to remote servers. To ensure against loss of information, the system needs a certain amount of redundancy. The current standard cloud storage technique, storage mirroring, achieves this by storing complete copies of the data on multiple servers. In Li and colleagues’ chosen technique, the redundant data blocks are instead scattered between servers. This has two advantages over storage mirroring. First, it reduces storage costs, since less redundancy is required; secondly, compromising one server does not lead to a complete data leak, even if the encryption algorithm is compromised. “Erasure coding is characterized by high fault tolerance, scalability and efficiency. It achieves highly reliable data recovery with smaller redundant blocks,” the researchers tell Physics World.

When a user wishes to recover the original data, the central server requests the data blocks from randomly chosen remote servers, reconstructs it and sends it in encrypted form back to the original user, who can recover the encryption key K and decrypt the message because they have the proportion of R that was originally retained locally as well as that which was inserted into the message. A hacker, however, could only obtain the part that was uploaded. The researchers write that they conducted a “minimal test system to verify the functionality and performance of our proposal” and that “the next step in developing this technology involves researching and validating multi-user storage technology. This means we will be focusing on how our system can effectively and securely handle data storage for multiple users.”

Further work needed

Barry Sanders, who directs the Institute for Quantum Science and Technology at the University of Calgary in Canada, describes a paper on the work in AIP Advances as “a good paper discussing some issues concerning how to make cloud storage secure in a quantum sense”. However, he believes more specifics are necessary. In particular, he would like to see a real demonstration of a distributed cloud storage system that meets the requirements one would expect in cybersecurity.

“They don’t do that, even in the ideal sense,” says Sanders, who holds an appointment at USTC but was not involved in this work. “What is the system you’re going to create? How does that relate to other systems? What are the threat models and how do we show that adversaries are neutralized by this technique? None of these are evident in this paper.”

Device-independent QKD brings unhackable quantum Internet closer

Renato Renner, who leads a quantum information theory research group at ETH Zurich, Switzerland, is similarly critical. “The positive part [of the paper] is that it at least tries to combine quantum-inspired protocols and integrate them into classical crytographic tasks, which is something one doesn’t see very often,” he says. “The issue I have is that this paper uses many techniques which are a priori completely unrelated – secret sharing is not really related to QKD, and quantum random number generation is different from QKD – they mix them all together, but I don’t think they make a scientific contribution to any of the individual ingredients: they just compose them together and say that maybe this combination is a good way to proceed.”

Like Sanders, Renner is also unconvinced by the team’s experimental test. “Reading it, it’s just a description of putting things together, and I really don’t see an added value in the way they do it,” he says.