Quantum technologies have enormous potential, but achieving that potential is not going to be cheap. The US, China and the EU have already invested more than $50 billion between them in quantum computing, quantum communications, quantum sensing and other areas that make up the so-called “second quantum revolution”. Other high-income countries, notably Australia, Canada and the UK, have also made significant investments. But what about the rest of the world? How can people in other countries participate in (and benefit from) this quantum revolution?

In a panel discussion at Optica’s Quantum 2.0 conference, which took place this week in Rotterdam in the Netherlands, five scientists from low- and middle-income countries took turns addressing this question. The first, Tatevik Chalyan, drew sympathetic nods from her fellow panellists and moderator Imrana Ashraf when she described herself as “part of the generation forced to leave Armenia to get an education”. Since then, she said, the Armenian government has become more supportive, building on a strong tradition of research in quantum theory. Chalyan, however, is an experimentalist, and she and many of her former classmates are still living abroad – in her case, as a postdoctoral researcher in silicon photonics at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium.

Another panellist, Vatshal Srivastav, followed a similar path, studying at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) in Kanpur before moving to the UK’s Heriot-Watt University to do his PhD and postdoc on higher-dimensional quantum circuits. He, too, thinks things are improving back home, with the quality of research in the IIT network becoming high enough that many of his friends chose to remain there. Countries that want to improve their research base, he said, should find ways to “keep good people within your system”.

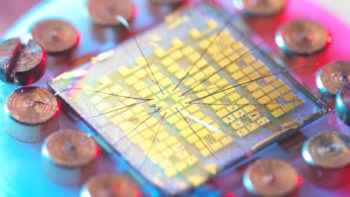

For panellist Taofiq Paraiso, who says he was “brought up in several African countries” before moving to EPFL in Switzerland for his master’s and PhD, the starting point is simple. “It’s about transferring skills and knowledge,” said Paraiso, who now leads a team developing chip-based hardware for quantum cryptography at Toshiba Europe’s Cambridge Research Laboratory in the UK. People who return to their home countries after being educated abroad have an important role to play in that, he added.

Returning is not always easy, though. The remaining two panellists, Roger Alfredo Kögler and Rodrigo Benevides, are both from Brazil, and Kögler, who did his PhD in Brazil’s Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia de Informação Quântica, said that Brazilians who want to become professors in their home country are strongly urged to go abroad for their postdoctoral research. But now that he has seen the resources available to him as a postdoc in nano-optics at the Humboldt University of Berlin, Germany, Kögler admitted that he is “rethinking whether I want to go back” even though he worries that staying in Europe would make him “part of the problem”.

It’s much easier to freely have ideas if you have a lot of money

Rodrigo Benevides

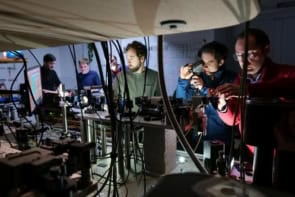

Benevides, whose PhD was split between Brazil’s University of Campinas and the Netherlands’ TU Delft, elaborated on the reasons for this dilemma. In Brazil, he and his colleagues “used to see all these papers in Nature or Science” while they were “in the lab just trying to make our laser work”. That kind of atmosphere, he said, “leads to a lack of self-confidence” because people begin to suspect that they, and not the system, are the problem. Now, as a postdoc working on hybrid quantum systems at ETH Zurich in Switzerland, Benevides wryly observed that “it’s much easier to freely have ideas if you have a lot of money”.

As for how to remedy these challenges, Benevides argued that the solutions will be diverse and tailored to local circumstances. As an example, Paraiso highlighted the work of an outreach organization, Photonics Ghana, that motivates students to engage with quantum science. He also suggested that cloud-based quantum computing and freely available software packages such as IBM’s Qiskit will help organizations that lack the resources to build a quantum computer of their own. Chalyan, for her part, pointed out that a lack of resources sometimes has a silver lining. Coming up with creative work-arounds, she said, “is what we are famous for [as] people from developing countries”.

Africa’s quantum future offers a beacon of hope

Finally, several panellists emphasized the need to focus on quantum technologies that will make a difference locally. Though Kögler warned that it is hard to predict what will turn out to be “useful”, a few answers are already emerging. “Maybe we don’t need quantum error correction, but we do need a quantum sensor that brings better agriculture,” Benevides suggested. Paraiso noted that information security is important in African countries as well as European ones, and added that quantum key distribution is one of the more mature quantum technologies. Whatever the specifics, though, Srivastav recommended identifying the problems your society is facing and figuring out how they overlap with your current research. “As scientists, it is our job to make things better,” he concluded.