By tuning the spatial dimension of an optical quantum gas from 2D to 1D, physicists at Germany’s University of Bonn and University of Kaiserslautern-Landau (RPTU) have discovered that it does not condense suddenly, but instead undergoes a smooth transition. The result backs up an important theory prediction concerning this exotic state of matter, allowing it to be studied in detail for the first time in an optical quantum gas.

Decreasing the number of dimensions from three to two to one dramatically influences the physical behaviour of a system, causing different states of matter to emerge. In recent years, physicists have been using optical quantum gases to study this phenomenon.

In the new study, conducted in the framework of the collaborative research centre OSCAR, a team led by Frank Vewinger of the Institute of Applied Physics (IAP) at the University of Bonn looked at how the behaviour of a photon gas changed as it went from being 2D to 1D. The researchers prepared the 2D gas in an optical microcavity, which is a structure in which light is reflected back and forth between two mirrors. The cavity was filled with dye molecules. As the photons repeatedly interact with the dye, they cool down and the gas eventually condenses into an extended quantum state called a Bose–Einstein condensate.

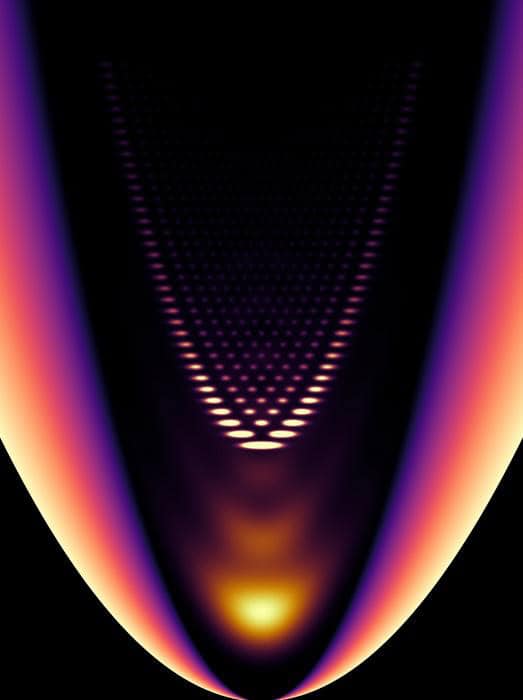

Parabolic-shaped protrusions

To make the gas 1D, they modified the reflective surface of the optical cavity by laser-printing a transparent polymer nanostructure on top of one of the mirrors. This patterning created parabolic-shaped protrusions that could be elongated and made narrower – and in which the photons could be trapped.

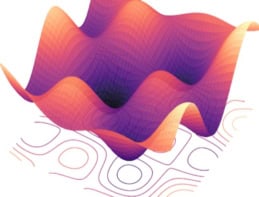

As the gas transitioned between the 2D and 1D structures, Vewinger and colleagues measured its thermal properties as it was allowed to come back to room temperature – by coupling it to a heat bath. Usually, there is a precise temperature at which condensation occurs – think of water freezing at precisely 0°C. The situation is different when a 1D gas instead of a 2D one is created, however, explains Vewinger. “So-called thermal fluctuations take place in photon gases but they are so small in 2D that they have no real impact. However, in 1D these fluctuations can – figuratively speaking – make big waves.”

These fluctuations destroy the order in 1D systems, meaning that different regions within the gas begin to behave differently, he adds. The phase transition therefore becomes more diffuse.

A difficult experiment

The experiment was not an easy one to set up, he says. The main challenge was to adapt the direct laser writing method to create small and steep structures in which to confine the photons so that it worked for the dye-filled microcavity. “We then had to analyse the photons emitted from the microcavity.”

“Our colleagues in Kaiserslautern eventually succeeded in fabricating new tiny polymer structures with high resolution, sticking to our ultra-smooth dielectric cavity mirrors (with a roughness of around 0.5 Å) that were robust to both the chemical solvent in our dye solution and the laser irradiation employed to inject photons into the cavity,” he tells Physics World.

Extremely compressible photon gas confirms peculiar prediction of quantum theory

It is often the case in physics that theories and predictions are based on simple toy models, and these models are powerful in building robust theoretical framework, he explains. “But nature is far from simple; it is extremely difficult to build these ideal platforms to test these foundational concepts since real-world systems are usually interacting, driven-dissipative or coupled to some other system. For photon condensates, it is known that they very closely resemble an ideal Bose gas coupled to a heat bath, so we were interested in using this platform to study the effect of the dimension on the phase transition to a Bose–Einstein condensate.”

Looking forward, the researchers say they will now use their novel technique to study more elaborate forms of photon confinement – such as logarithmic or Coulomb-like confinement. They also plan to study photons confined in large lattice structures in which stable vortices can form without particle–particle interactions. “For example, in one-dimensional chains, there are predictions of an exotic zig-zag phase, induced by incoherent hopping between lattice sites,” says Vewinger. “In essence, the structuring opens up a large playground for us in which to study interesting physics.”

The present study is detailed in Nature Physics.