Ahead of the 2024 Nobel Prize for Physics, Physics World editors recall amusing brushes with Nobel laureates past and present. Here, Margaret Harris remembers a tongue-in-cheek e-mail exchange with 1973 laureate Brian Josephson

Amid the hype of Nobel Prize week, it’s important to remember that in many respects, Nobel laureates are just like the rest of us. They wake up and get dressed. They eat. They go about their daily lives. And when it’s time for bed, they lie down on mattresses that have been rotated scientifically, according to the principles of symmetry group theory.

Well, Brian Josephson does, anyway.

In the early 1960s, Josephson – then a PhD student in theoretical condensed matter physics at the University of Cambridge, UK – predicted that a superconducting current should be able to tunnel through an insulating junction even when there is no voltage across it. He also predicted that if a voltage is applied, the current will oscillate at a well-defined frequency. These predictions were soon verified experimentally, and in 1973 he received a half share of the Nobel Prize for Physics (Ivar Giaever and Leo Esaki, who did experimental research on quantum tunnelling in superconductors and semiconductors respectively, got the other half).

Subsequent work has borne out the importance of Josephson’s discovery. “Josephson junctions” are integral to instruments called SQUIDs (superconducting quantum interference devices) that measure magnetic fields with exquisite sensitivity. More recently, they’ve become the foundation for superconducting qubits, which drive many of today’s quantum computers.

Josephson himself, however, lost interest in theoretical condensed-matter physics. Instead, he has devoted most of his post-PhD career to the physics of consciousness, researching topics such as telepathy and psychokinesis under the auspices of the Mind-Matter Unification Project he founded.

An unusual scientific paper

Josephson’s later work hasn’t attracted much support from his fellow physicists. Still, he remains an active member of the community and, incidentally, a semi-regular contributor to Physics World’s postbag. It was in this context that I learned of his work on the pressing domestic dilemma of mattress rotation.

In December 2014, Josephson responded to a call for submissions to Physics World’s Lateral Thoughts column of humorous essays with a brief but tantalizing message. “What a pity my ‘Group Theory and the Art of Mattress Turning’ is too short for this,” he wrote. This document, Josephson explained, describes “the order-4 symmetry group of a mattress, and how an alternating sequence of the two easiest non-trivial group operations…takes you in sequence through all four mattress orientations, thereby preserving as much as possible the symmetry of the mattress under perturbations by sleepers [and] enhancing its lifetime.”

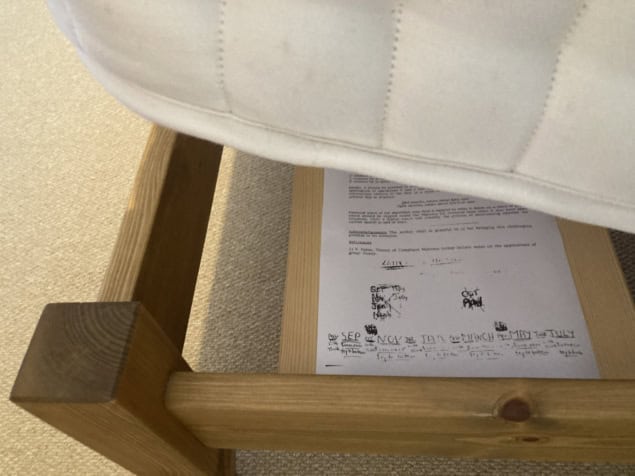

At the time, I had only recently purchased my first mattress, and I was keen to avoid shelling out for another any time soon. I therefore asked for more details. Within days, Josephson kindly replied with a copy of his mock paper, in the form of a scanned “cribsheet” which, he explained, lives under the mattress in the home he shares with his wife.

An argument from symmetry

Like all good scientific papers, Josephson’s “Group Theory and the Art of Mattress Turning” begins with a summary of the problem. “A mattress may be laid down on a bed in four different orientations,” it states. “For maximum life it should be cycled regularly through these four orientations. How may a mattress user ensure that this be done?”

The paper goes on to observe that the symmetry group of a mattress (that is, the collection of all transformations under which it is mathematically invariant) contains four elements. The first element is the identity transformation, which leaves the mattress’ orientation unchanged. The other three elements are rotations about the mattress’ axes of symmetry. Listed “in order of increasing physical effort required to perform”, these rotations are:

- V, rotation by π (180 degrees) about a vertical axis (that is, keeping the mattress flat and spinning it around so that the erstwhile head area is at the feet)

- L, rotation by π about the longer axis of symmetry (that is, flipping the mattress from the side of the bed, such that the head and foot ends remain in the same position relative to the bed, but the mattress is now upside down)

- S, rotation by π about the shorter axis of symmetry (that is, flipping the mattress from the end of the bed, such that the head and foot ends swap places while the mattress is simultaneously turned upside down)

“Ideally, S should be avoided in order to minimize effort”, the paper continues. Fortunately, there is a solution: “It is easily seen that alternate applications of V and L will cause the mattress to go through all ‘proper’ orientations relative to the bed, in a cycle of order 4. The following algorithm will achieve this in practice: Odd months, rotate about the lOng axis. eVen months, rotate about the Vertical axis.” In case this isn’t memorable enough, the paper advises that “potential users of this algorithm may find it helpful to write it down on a piece of paper which should be slipped under the mattress for retrieval later when it may have been forgotten”.

A challenging problem

The paper concludes, as per convention, with an acknowledgement section and a list of references. In the former, Josephson thanks “cj” – presumably his wife, Carol – “for bringing this challenging problem to my attention”. The latter contains a single citation, to a “Theory of Compliant Mattress Group lecture notes on applications of group theory” supposedly produced by Josephson’s office-mate Volker Heine.

Life beyond the Nobel: Brian Josephson and his interest in the mind

The most endearing part of the paper, though, is the area below the references in the scanned cribsheet. This contains extensive handwritten notes on months and rotations, strongly suggesting that Josephson does, in fact, rotate his mattress according to the above-outlined principles. Indeed, in a postscript to his e-mail, Josephson noted that he and Carol recently had to modify the algorithm in response to a change in experimental conditions, namely the purchase of “a very flexible foam mattress”. This, he observed, “makes S rotations easier than L rotations, so we use that instead”.

I wish I could say that I adopted this method of mattress rotation in my own domestic life. Alas, my housekeeping is not up to Nobel laureate standards: I rotate my mattress approximately once a season, not once a month as the algorithm requires. However, whenever I do get round to it, I always think of Brian Josephson, the unconventional Nobel laureate whose tongue-in-cheek determination to apply physics to his daily life never fails to make me smile.

SmarAct proudly supports Physics World‘s Nobel Prize coverage, advancing breakthroughs in science and technology through high-precision positioning, metrology and automation. Discover how SmarAct shapes the future of innovation at smaract.com.