Described as “the Glastonbury of quantum events” by one speaker, the UK National Quantum Technologies Showcase 2024 last week was the first time I have ever queued for a physics event. Essentially a quantum trade show, the showcase has been running for a decade, and in that time its attendance has grown from 100 to nearly 2000. It’s run by Innovate UK in collaboration with the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) and the UK National Quantum Technologies Programme (NQTP).

Nearly 100 quantum companies exhibited and there were talks and panels throughout the day. The mood was triumphant – last year the UK government announced the next phase of the NQTP, backed by a £2.5 billion 10-year quantum strategy, and in September, five quantum hubs were launched at British universities (with some overlap with the four previous hubs). However, for a sector that’s still finding its feet, the increasing focus on commercialization and industry creates some interesting tensions.

Commitment to quantum

Most of the funding for quantum technologies research in the UK comes from the public sector, and in the wake of the election of a new government, the organizers clearly felt a need to assuage post-election jitters.

The first speaker was Dave Smith, the UK’s national technology adviser, who gave an ambitious outline of the next decade of the government’s quantum strategy, which he expects to “grow the economy and make people’s lives better”. To do this, the UK quantum sector needs two things: talent and money. Smith’s speech focussed on the need to attract overseas talent, train apprentices and PhD students, and encourage private investors to dip their toes into quantum.

“We’ve gone from the preserve of academia to real-world applications” said Stella Peace, the recently appointed interim executive chair of Innovate UK, who spoke next. Her address made similar points to Smith, emphasizing that as well as funding quantum directly, Innovate UK aims to create connections between academia and industry that will grow the sector.

One senior figure with experience of the industry, government and academia aspects of quantum technology is the physicist Peter Knight from Imperial College London, who has been involved in the NQTP since it started and is now the chair of its strategic advisory board. Knight gave an insightful first-hand account of the last decade of the UK’s quantum programme. He said he was reassured that the new government is committed to quantum technology, but as with anything involving billions of pounds, making this a priority hasn’t been easy and Knight’s work is far from over. He described the researchers who led the first quantum hubs as “heroes” but added that “you can be heroic and fail”. According to Knight, to realize the potential of quantum technologies, “we need more than heroes, we need money”.

I spent the rest of the day alternating between the exhibition area and the talks. I saw established companies like Toshiba and British Telecom (BT) that are branching into quantum, as well as start-ups including Phasecraft and Quantum Dice.

A lively panel event on quantum skills was a particular highlight. The quantum sector faces a shortage of engineers, and the panellists debated whether quantum science should be integrated into existing engineering degrees and apprenticeships. A dissenting voice came from Rhys Morgan, the director of engineering and education at the Royal Academy of Engineering. “I’m not sure I agree with the need for a quantum apprenticeship,” he said, arguing that quantum companies should be training engineers on the job rather than expecting them to specialize during their degree.

Quantum at the crossroads

The UK government plans to invest £2.5bn in quantum technologies over the next decade and wants to attract an additional £1bn from private investment. The goal is to achieve a “quantum-enabled economy” by 2033. “Over the next 10 years,” states the National Quantum Strategy, “quantum technologies will revolutionize many aspects of life in the UK and bring enormous benefits to the UK economy, society and the way we can protect our planet.”

This is a bold statement. It sounds like the government expects to start getting a return on its quantum investment in the near future. But is that realistic?

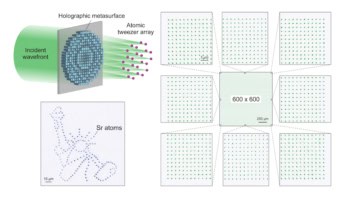

“Quantum technologies” is an imprecise term, but where it refers to computing and communications, it’s still firmly in the research phase of research and development. Even quantum sensing start-ups like Cerca Magnetics and Delta G are just starting to move towards commercialization. Quantum research has made huge strides but scientists and companies should be realistic about its current capabilities and advocate for space and time to explore work that might not come to fruition in the next decade.

This was summed up in the final address from Roger Mckinley, the quantum technologies challenge director at UK Research and Innovation (UKRI). His message to the government was that quantum commercialization is going to happen, but that they need to ask themselves: “How much do you want this to happen in the UK?”

Whatever you think about the hype over quantum technologies, researchers in the UK can celebrate the last decade, in which the country has punched above its weight in terms of quantum investment and research. However, there’s a lot of work still to do. If quantum researchers are serious about bringing these technologies to the real world, they should be prepared to keep fighting for them.