Ian Randall reviews LUNAR: a History of the Moon in Myths, Maps + Matter

As I write this [and don’t tell the Physics World editors, please] I’m half-watching out of the corner of my eye the quirky French-made, video-game spin-off series Rabbids Invasion. The mad and moronic bunnies (or, in a nod to the original French, Les Lapins Crétins) are currently making another attempt to reach the Moon – a recurring yet never-explained motif in the cartoon – by stacking up a vast pile of junk; charming chaos ensues.

As explained in LUNAR: a History of the Moon in Myths, Maps + Matter – the exquisite new Thames & Hudson book that presents the stunning Apollo-era Lunar Atlas alongside a collection of charming essays – madness has long been associated with the Moon. One suspects there was a good kind of mania behind the drawing up of the Lunar Atlas, a series of geological maps plotting the rock formations on the Moon’s surface that are as much art as they are a visualization of data. And having drooled over LUNAR, truly the crème de la crème of coffee-table books, one cannot fail but to become a little mad for the Moon too.

As well as an exploration of the Moon’s connections (both etymologically and philosophically) to lunacy by science writer Kate Golembiewski, the varied and captivating essays of 20 authors collected in LUNAR cover the gamut from the Moon’s role in ancient times (did you know that the Greeks believed that the souls of the dead gather around the Moon?) through to natural philosophy, eclipses, the space race and the Artemis Programme. My favourite essays were the more off-beat ones: the Moon in silent cinema, for example, or its fascinating influence on “cartes de visite”, the short-lived 19th-century miniature images whose popularity was boosted by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. (I, for one, am now quite resolved to have my portrait taken with a giant, stylized, crescent moon prop.)

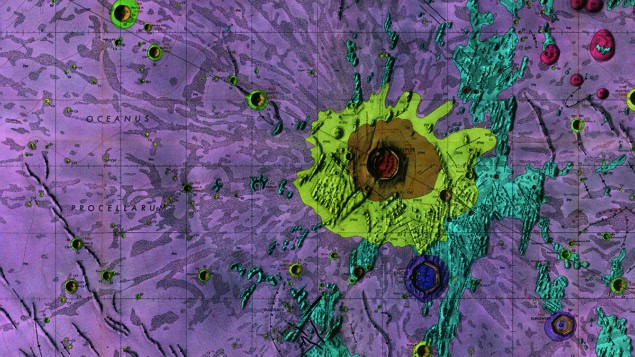

The pulse of LUNAR, however, are the breathtaking reproductions of all 44 of the exquisitely hand-drawn 1:1,000,000 scale maps – or “quadrangles” – that make up the US Geological Survey (USGS)/NASA Lunar Atlas (see header image).

Drawn up between 1962 and 1974 by a team of 24 cartographers, illustrators, geographers and geologists, the astonishing Lunar Atlas captures the entirety of the Moon’s near side, every crater and lava-filled maria (“sea”), every terra (highland) and volcanic dome. The work began as a way to guide the robotic and human exploration of the Moon’s surface and was soon augmented with images and rock samples from the missions themselves.

One could be hard-pushed to sum it up better than the American science writer Dava Sobel, who pens the book’s foreword: “I’ve been to the Moon, of course. Everyone has, at least vicariously, visited its stark landscapes, driven over its unmarked roads. Even so, I’ve never seen the Moon quite the way it appears here – a black-and-white world rendered in a riot of gorgeous colours.”

Many moons ago

Having been trained in geology, the sections of the book covering the history of the Lunar Atlas piqued my particular interest. The Lunar Atlas was not the first attempt to map the surface of the Moon; one of the reproductions in the book shows an earlier effort from 1961 drawn up by USGS geologists Robert Hackman and Eugene Shoemaker.

Hackman and Shoemaker’s map shows the Moon’s Copernicus region, named after its central crater, which in turn honours the Renaissance-era Polish polymath Nicolaus Copernicus. It served as the first demonstration that the geological principles of stratigraphy (the study of rock layers) as developed on the Earth could also be applied to other bodies. The duo started with the law of superposition; this is the principle that when one finds multiple layers of rock, unless they have been substantially deformed, the older layer will be at the bottom and the youngest at the top.

“The chronology of the Moon’s geologic history is one of violent alteration,” explains science historian Matthew Shindell in LUNAR’s second essay. “What [Hackman and Shoemaker] saw around Copernicus were multiple overlapping layers, including the lava plains of the maria […], craters displaying varying degrees of degradations, and materials and features related to the explosive impacts that had created the craters.”

From these the pair developed a basic geological timeline, unpicking the recent history of the Moon one overlapping feature at the time. They identified five eras, with the Copernican, named after the crater and beginning 1.1 billion years ago, being the most recent.

Considering it was based on observations of just one small region of the Moon, their timescale was remarkably accurate, Shindell explains, although subsequent observations have redefined its stratigraphic units – for example by adding the Pre-Nectarian as the earliest era (predating the formation of Nectaris, the oldest basin), whose rocks can still be found broken up and mixed into the lunar highlands.

Accordingly, the different quadrants of the atlas very much represent an evolving work, developing as lunar exploration progressed. Later maps tended to be more detailed, reflecting a more nuanced understanding of the Moon’s geological history.

New moon

Parts of the Lunar Atlas have recently found new life in the development of the first complete map of the lunar surface, the “Unified Geologic Map of the Moon”. The new digital map combines the Apollo-era data with that from more recent satellite missions, including the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA)’s SELENE orbiter.

As former USGS Director and NASA astronaut Jim Reilly said when the unified map was first published back in 2020: “People have always been fascinated by the Moon and when we might return. So, it’s wonderful to see USGS create a resource that can help NASA with their planning for future missions.”

I might not be planning a Moon mission (whether by rocket or teetering tower of clutter), but I am planning to give the stunning LUNAR pride of place on my coffee table next time I have guests over – that’s how much it’s left me, ahem, “over the Moon”.

- 2024 Thames and Hudson 256pp £50.00