A new statistical physics analysis of the French labour market has revealed that the vast majority of occupations act as so-called condenser occupations. These structural bottlenecks attract workers from many other types of jobs, but offer very limited options for further mobility. This finding could help explain why changing jobs in response to shocks like technological change or economic crises is often so slow, say scientists at the Ecole Polytechnique in Paris, who performed the study.

“By pinpointing where mobility gets ‘stuck’, we provide a new lens to understand – and potentially improve – the adaptability of labour markets,” explains Max Knicker of the EconophysiX lab, who led this new research effort.

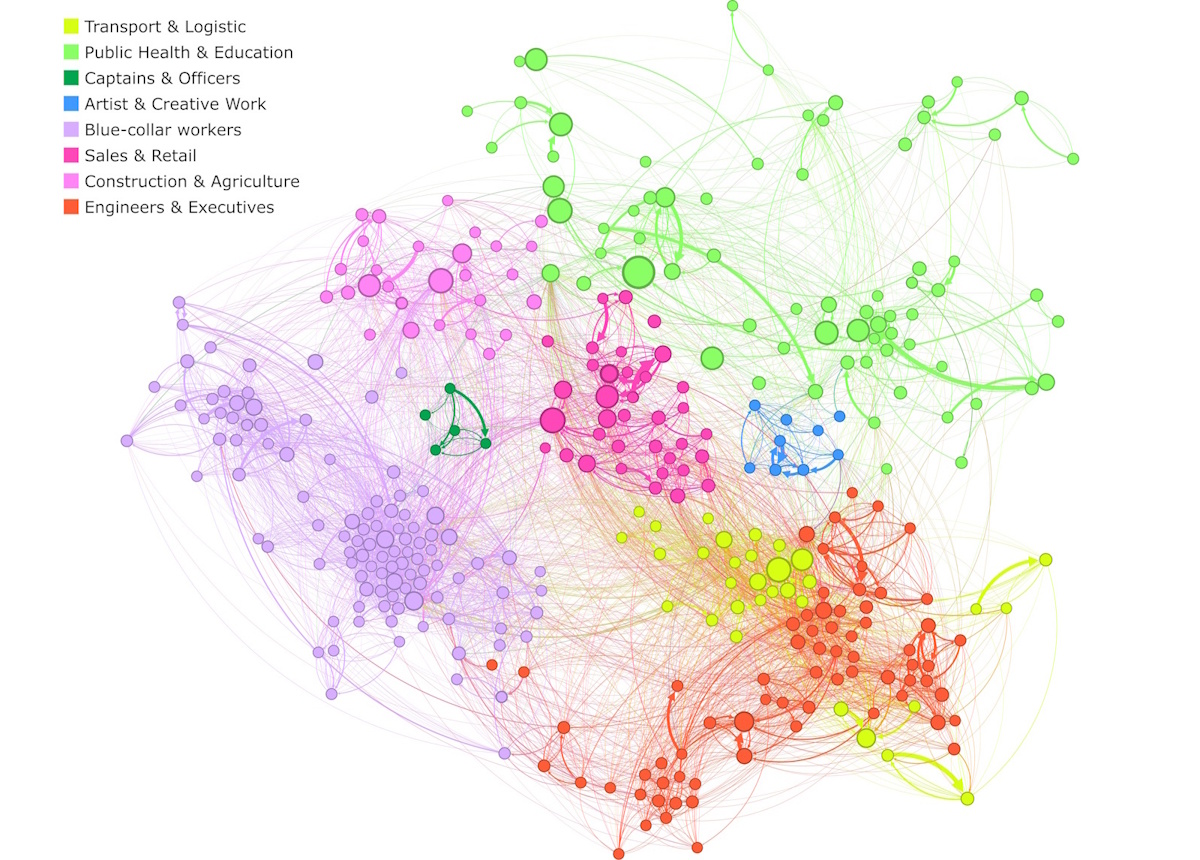

Knicker and colleagues borrowed a concept from statistical physics known as the “fitness and complexity” framework, which is used to study the structure of economies and ecosystems. In their work, the researchers treated occupations as nodes in a network and analysed real transition data – that is, how workers actually moved between different jobs in France from 2012 to 2020. The data came from official sources and were provided by the National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies through the Secure Data Access Center (CASD).

“In total, we had access to information on about 30 million workers and employers in France, whom we tracked over a 10-year period,” explains Knicker. “We also worked with high-resolution administrative data from INSEE (the French National Institute of Statistics), and specifically the BTS-Postes (Base Tous Salariés-Postes).”

Two key metrics

The researchers assigned a score for each occupation and developed two key metrics. These were: accessibility, which measures how many different jobs “feed into” a given occupation; and transferability, which measures how many different jobs someone can move to from that occupation.

By studying the network of job flows with these metrics, they observed hidden patterns and constraints in occupational mobility and identified four main clusters, or categories, of jobs. The first are defined as “diffuser” occupations and have high transferability but low accessibility. “These require specific training to enter, but that training allows for transitions to many other areas,” explains Knicker. “This means they are more difficult to get into, but offer a wide range of exit opportunities.”

The second group are called “channel” occupations. These are both hard to enter and offer few onward transitions, he says. “They often involve highly specialized skills, such as specific types of machine operation.”

The third class are “hubs” and are both widely accessible and highly transferable – so much so that they act as central nodes in the transition network. “This class includes jobs like retail sellers, which require a broad, yet not highly specialized skill set,” says Knicker.

The fourth and last category is the most common type and dubbed “condenser” occupations. “Workers from many different backgrounds can easily enter these, but they can’t easily get out afterwards,” explains Knicker. “Examples of such jobs include caregiving roles.”

A valuable tool for policymakers

The researchers explain that they undertook their study to answer a broader question: why do some economies adapt quickly to shocks while others struggle? “Despite increasing attention to issues like automation or the green transition, we still lacked tools to diagnose where worker mobility breaks down,” says Knicker. “A key challenge was dealing with the sheer complexity and size of the labour flow data – we analysed over 250 million person–year observations. Another was interpreting the results in a meaningful, policy-relevant way, since the transition network is shaped by many intertwined factors like skill compatibility, employer preferences and worker choices.”

The new framework could become a valuable tool for policymakers seeking to make labour markets more responsive, he tells Physics World. “For example, by identifying specific occupations that function as bottlenecks, we can better target reskilling efforts or job transition programmes. It also suggests that simply increasing training isn’t enough – what matters is where people are coming from and where they can go next.”

Breaking boundaries: physicist bags 2022 economics Nobel

The researchers also showed that the structure of job transitions itself can limit mobility. Over time, this could inform the design of more strategic labour interventions, especially in the face of structural shocks like AI-driven job displacement, states Knicker.

Looking forward, the Ecole Polytechnique team plans to extend its approach by studying how the career paths of individual workers evolve over time. This, says Knicker, will be done using panel data, not just year-to-year snapshots as in the present analysis. He and his colleagues are also interested in linking their metrics to wage dynamics – for example, does low transferability make workers more vulnerable to exploitation or wage stagnation? “Finally, we hope to explore whether similar bottleneck structures exist in other countries, which could reveal whether these patterns are universal or country-specific.”

Full details of the analysis are reported in the Journal of Statistical Mechanics Theory and Experiment.