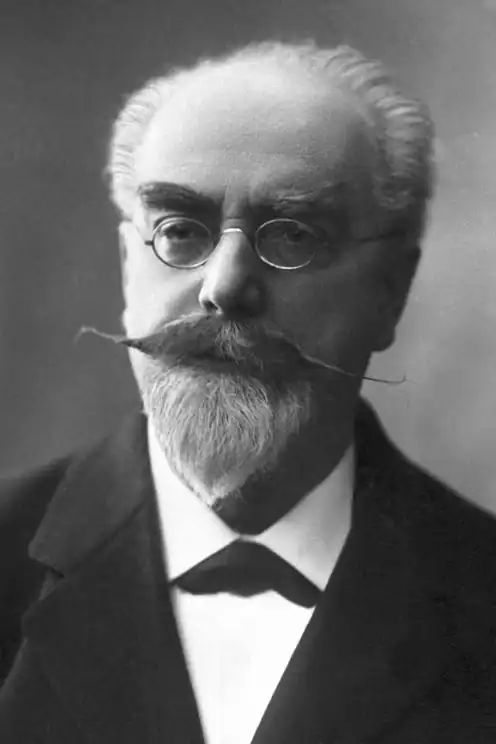

By the time Gabriel Lippmann won the Nobel Prize for Physics, his crowning scientific achievement was already obsolete – and he probably knew it. Four days after receiving the 1908 prize “for his method of reproducing colours photographically based on the phenomenon of interference”, Lippmann, a Frenchman with a waxed moustache that would shame a silent film villain, ended his Nobel lecture with the verbal equivalent of a Gallic shrug.

After nearly 20 years of work, he admitted, the minimum exposure time for his method – one minute in full sunlight – was still “too long for the portrait”. Though further improvements were possible, he concluded, “Life is short and progress is slow.”

Why did Lippmann win a Nobel prize for a method that not even he seemed to believe in? It certainly wasn’t for a lack of alternatives. The early 1900s were a heady time for physics discoveries and inventions, and other Nobels of the era reflect this. In 1906 the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded the physics prize to J J Thomson for discovering the electron. In 1907 its members voted for Albert Michelson of the aether-defying Michelson–Morley experiment. So what made the Academy choose, in 1908, a version of colour photography that wouldn’t even let you take a selfie?

An elegant solution

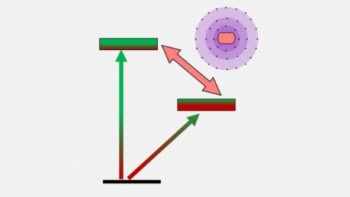

Let’s start with the method itself. Unlike other imaging processes, Lippmann photography directly records the entire colour spectrum of an object. It does this by using standing waves of light to produce interference fringes in a light-sensitive emulsion backed by a mirrored surface. The longer the wavelength of light given off by the object, the larger the separation between the fringes. It’s an elegant application of classical wave theory. It’s easy to see why Edwardian-era physicists loved it.

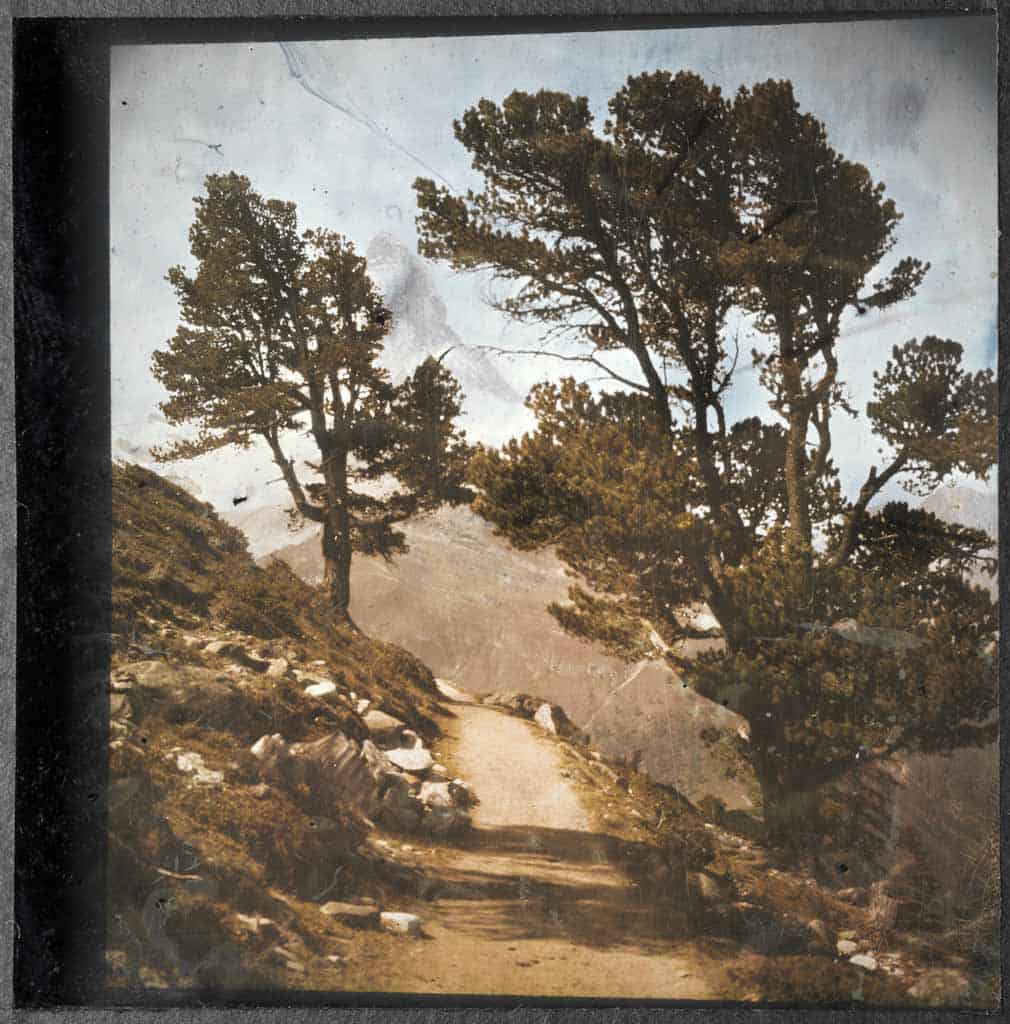

Lippmann’s method also has an important practical advantage. Because his photographs don’t require pigments, they retain their colour over time. Consequently, the images Lippmann showed off in his Nobel lecture look as brilliant today as they did in 1908.

The method’s disadvantages, though, are numerous. As well as needing long exposure times, the colours in Lippmann photographs are hard to see. Because they are virtual, like a hologram, they are only accurate when viewed face-on, in perpendicular light. Lippmann’s original method also required highly toxic liquid mercury to make the mirrored back surface of each photographic plate. Though modern versions have eliminated this, it’s not surprising that Lippmann’s method is now largely the domain of hobbyists and artists.

A French connection

If technical merit can’t explain Lippmann’s Nobel, could it perhaps have been due to politics? The easiest way to answer this question is to look in the Nobel archives. Although the names of Nobel prize nominees and the people who nominated them are initially secret, this secrecy is lifted after 50 years. The nomination records for Lippmann’s era are therefore very much available, and they show that he was a popular candidate. Between 1901 and 1908, he received 23 nominations from 12 different people – including previous laureates, foreign members of the Academy, and scientists from prestigious universities invited to make nominations in specific years.

Funnily enough, though, all of them were French.

Faced with this apparent conspiracy to stamp the French tricolour on the Nobel medal, Karl Grandin, who directs the Academy’s Center for History of Science, concedes that such nationalistic campaigns were “quite common in the first years”. However, this doesn’t mean they were successful: “Sometimes when all the members of the French Academy have signed a nomination, it might be impressive at one point, but it might also be working in the opposite way,” he says.

A clash of personalities

Because Nobel Foundation statutes stipulate that discussions and vote numbers from the prize-awarding meeting of the Academy are not recorded, Grandin can’t say exactly how Lippmann came out on top in 1908. He does, however, have access to an illuminating article written in 1981 by a theoretical physicist, Bengt Nagel.

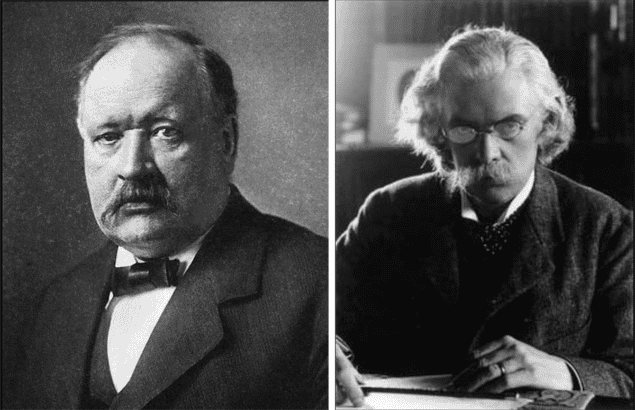

Drawing on the private letters and diaries of Academy members as well as the Nobel archives, Nagel showed that personal biases played a significant role in the awarding of the 1908 prize. It’s a complicated story, but the most important strand of it centres on Svante Arrhenius, the Swedish physical chemist who’d won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry five years earlier.

Today, Arrhenius is best known for predicting that putting carbon dioxide in the Earth’s atmosphere will affect the climate. In his own lifetime, though, Grandin says that Arrhenius was also known for having a long-running personality conflict with a wealthy Swedish mathematician called Gustaf Mittag-Leffler.

“Stockholm at the time was a small place,” Grandin explains. “Everyone knew each other, and it wasn’t big enough to host both Arrhenius and Mittag-Leffler.”

Arrhenius wasn’t the chair of the Nobel physics committee in 1908. That honour fell to Knut Angstrom, son of the Angstrom the unit is named after. Still, Arrhenius’ prestige and outsized personality gave him considerable influence. After much debate, the committee agreed to recommend his preferred choice for the prize, Max Planck, to the full Academy.

This choice, however, was not problem-free. Planck’s theory of the quantization of matter was still relatively new in 1908, and his work was not demonstrably guiding experiments. If anything, it was the other way around. In principle, the committee could have dealt with this by recommending that Planck share the prize with a quantum experimentalist. Unfortunately, no such person had been nominated.

That was awkward, and it gave Mittag-Leffler the ammunition he needed. When the matter went to the Academy for a vote, he used members’ doubts about quantum theory to argue against Arrhenius’ choice. It worked. In Mittag-Leffler’s telling, Planck got only 13 votes. Lippmann, the committee’s second choice, got 46.

A consensus winner

Afterwards, Mittag-Leffler boasted about his victory. “Arrhenius wanted to give it to Planck…but his report, which he had nevertheless managed to have unanimously accepted by the committee, was so stupid that I could easily have crushed it,” he wrote to a French colleague. “Two members even declared that after hearing me, they changed their opinion and voted for Lippmann. I would have had nothing against sharing the prize between [quantum theorist Wilhelm] Wien and Planck,” Mittag-Leffler added, “but to give it to Planck alone would have been to reward ideas that are still very obscure and require verification by mathematics and experimentation.”

Lippmann’s work posed no such difficulties, and that seems to have swung it for him. In a letter to a colleague after the dust had settled, Angstrom called Lippmann “obviously a prizeworthy candidate who did not give rise to any objections”. However, Angstrom added, he “could not deny that the radiation laws constitute a more important advance in physical science than Lippmann’s colour photography”.

Nobel prizes you’ve never heard of: how a Swedish inventor was honoured for a technology that nearly killed him

Much has been written about excellent scientists getting overlooked for prizes because of biases against them. The flip side of this – that merely good scientists sometimes win prizes because of biases in their favour – is usually left unacknowledged. Nevertheless, it happens, and in 1908 it happened to Gabriel Lippmann – a good scientist who won a Nobel prize not because he did the most important work, but because his friends clubbed together to support him; because Academy members were wary of his quantum rivals; and above all because a grudge-holding mathematician and an egotistical chemist had a massive beef with each other.

And then, four years later, it happened again, to someone else.